Summer Stories: ‘Avoid the Darkness’

By Liina Koivula

Shirley hustled her kid through the door of my apartment building and told me the train was coming in, the one with nuclear warheads our action group was protesting.

“I need to be there,” I said. My body had no worthy use besides obstructing forces of annihilation. But Shirley had been involved longer.

“Jimmy, I need you to stay with Leo, please.”

It was 6:30 on a cold February morning in 1985. I waved for her to go.

The kid took my hand, all solemn. We went up the curved staircase of the once-opulent building where I rented a studio. Leo was an unsmiling, unnerving 5-year-old and I was 19, too old to babysit.

“Why do you have a tent in here?” Leo asked. I’d moved to Spokane in September, after the mountain mornings in Montana grew frosty. I left the murphy bed in the wall and pitched my one-man tent in the sleeping alcove.

“It’s cooler than a bed. Don’t you think?” Leo was skeptical. He went directly to the old dumbwaiter, nailed shut for years, and told me there was a ghost stuck inside.

“No, there isn’t,” I said, scalp prickling.

“There is. He goes up and down, up, down.”

I’d been a creepy kid, too. My mother’s favorite story to tell at a champagne brunch: as a small child, a neighbor dropped me off at home around twilight. Well after nightfall, my parents found me standing in the dark driveway, a silent ghoul.

My mother would throw her head back with a shriek of laughter, and her hairdo wouldn’t move. She had it set at the salon every Tuesday and slept sitting up. I assumed she and my dad had made love just once. I had no siblings.

In a decade-old photograph, the three of us stand on a bridge. I’m nine years old and ready to spring, vitalized by the force of the Spokane River shoving over the lower falls. My parents each clutch one of my shoulders, holding me in place like clothespins. They soon set me loose at the World’s Fair, Expo ’74, while they drank in a steakhouse bar. For years, I daydreamed I’d hidden among the exhibits and started a new life in Spokane as an orphan.

It took me until my high school graduation ceremony to follow through with plans to run away from our rambler outside of Tacoma. On the all-night drive into Montana, I amused myself picturing my folks cramped and cranky in the bleachers waiting to hear my name called (so that we could celebrate at a steakhouse, where they could have a drink), their displeasure when I never crossed the stage.

I was a born fugitive, like the nature writer Loren Eiseley. Possessed of a subterranean longing for dark caves, based in his youthful sewer exploration, he said more choices than we would like to believe are made during childhood. True: I’d fixated on ecological protection since wandering the Vanishing Species hall at the Expo. Camping alone in Glacier, I determined the best way to live in the woods was to be a writer, and the best way to be a writer was to live in the woods. I privately considered myself an English major when I registered for community college classes, adding a science elective in conservation.

My classmate Shirley was a second-year Natural Resources student. She’d spent the summer working for the Bureau of Land Management, earning enough to pay her tuition and support herself and her young son for the year, until she graduated and secured a job with the Forest Service. A starry-eyed environmentalist, I was quick to argue, loudly, against clearcutting, nuclear arms, and clearcutting to make way for nuclear arms, which I had protested on the peninsula naval base during high school. Shirley, also opposed to nuclear armament but able to say “clearcut” without cringing, jumped into my game, and we verbally sparred until our professor told us to knock it off. After class, we smirked at one another. Arguing with my folks left me wrung out and depressed, but with Shirley, I felt invigorated, evenly matched, carried along like the current over a waterfall. We agreed to do our midterm project together, and I joined her, along with Quakers, Mennonites and old hippies, at disarmament meetings.

Which led to minding her kid while she faced arrest. In my apartment, I picked up the one object that could pass as a toy.

“You can read, right?”

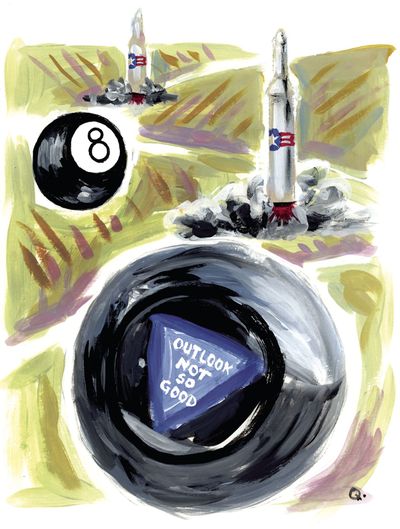

Leo nodded. I handed him my Magic 8 Ball and showed him how to use it. “Ask if there is a ghost in the wall.”

“Signs point to yes,” the Magic 8 Ball said. I made an involuntary sound in the back of my throat and Leo looked concerned.

We had oatmeal for breakfast. Leo shook the Magic 8 Ball, scowling at the answers to the questions in his mind.

“Ask if we should join your mom.” I was itchy for a bigger risk, a bigger thrill, outside the safety of group protest. I was drawing a mental map of escape, like the visionary artists and scientists Loren Eiseley wrote about. My worthless body would be transformed into a tool for peace in front of the train. I held the ultimate bargaining chip to take Shirley’s place. Her kid.

I watched over Leo’s shoulder while the Magic 8 Ball floated its triangular message in blue goo. “Outlook not so good.”

“Let’s go,” I said.

By the tracks, 60 protesters prayed that the crew would change their minds about transporting what amounted to the complete destruction of life on earth. We were all endangered species if we couldn’t stop this train, due to pass in 90 minutes. Shirley and three others stood on the creosote railroad ties. Her cheeks were ruddy with the rigor of using her body to do right. I needed to feel that. I quietly told Leo to say hi to his mom.

“Hey, Mama,” he shouted.

Shirley turned her head in alarm and caught my eye. Disappointment, disgust.

She rushed over and took Leo’s hand.

“Jimmy.” Resentment, resignation. “Fine, go.”

Shirley handed over the sign she’d been waving: 1,440 Hiroshimas. Linked arms with a comrade. Closed her eyes, in prayer, I guess. Refusing me something. Shutting me out.

My heart began to rot as I floated onto the tracks, all wrong.

The next day, I knocked at the door of Shirley’s ramshackle house in Peaceful Valley. I didn’t know if I was there to argue, to apologize, or to beg for her sympathy.

Shirley removed a half-apron tied around her hips and slipped into a jacket. She said, “You look like hell, Jimmy.”

“I spent the night in jail.”

“I know.”

The other three had been released by evening with criminal trespass citations, but I’d messed up, obstructed a police officer and resisted arrest.

“Can we talk?”

“My friend’s asleep,” she said. “Let’s walk.” I was the one who needed a nap, but I guessed it was a different kind of friend who was in her bed on a weekday afternoon. “We can pick Leo up from school soon.”

We made our way along the river, then onto the Monroe Street Bridge.

“I didn’t want you to put your career in jeopardy,” I said. “Government agencies.”

“Come off it. You got what you wanted. Your name is in the paper.” Maybe my name would reach my folks in Tacoma.

We looked out over the falls. I wondered aloud why the cascade seemed less potent now than in my old family photo at the same location.

“The power company controls the water. At dusk it’s diverted into turbines. Expo organizers convinced them to increase the flow, for the spectacle.”

I didn’t know that.

I didn’t know anything.

The righteous elation I sought had evaded me even before I went limp and let myself be dragged to the police cruiser. The train passed while I was being booked, prayers unanswered.

I had peeked into Shirley’s home when she opened the door. A warmth, almost a glow, emanated from weavings, quilts, houseplants. I fundamentally misunderstood how to live, replacing my parents’ middle-class trappings with nothing. A sleeping bag in an unadorned room, my own clammy cave in Eiseley’s Night Country. “Avoid the darkness,” he wrote. “It is a simple prescription, but you will not follow it.”

I wanted Shirley to let me into the light.

I understood she could not.

Her friend was asleep in her room.