The greatest night of Noah Lyles’s life was fueled by his lowest

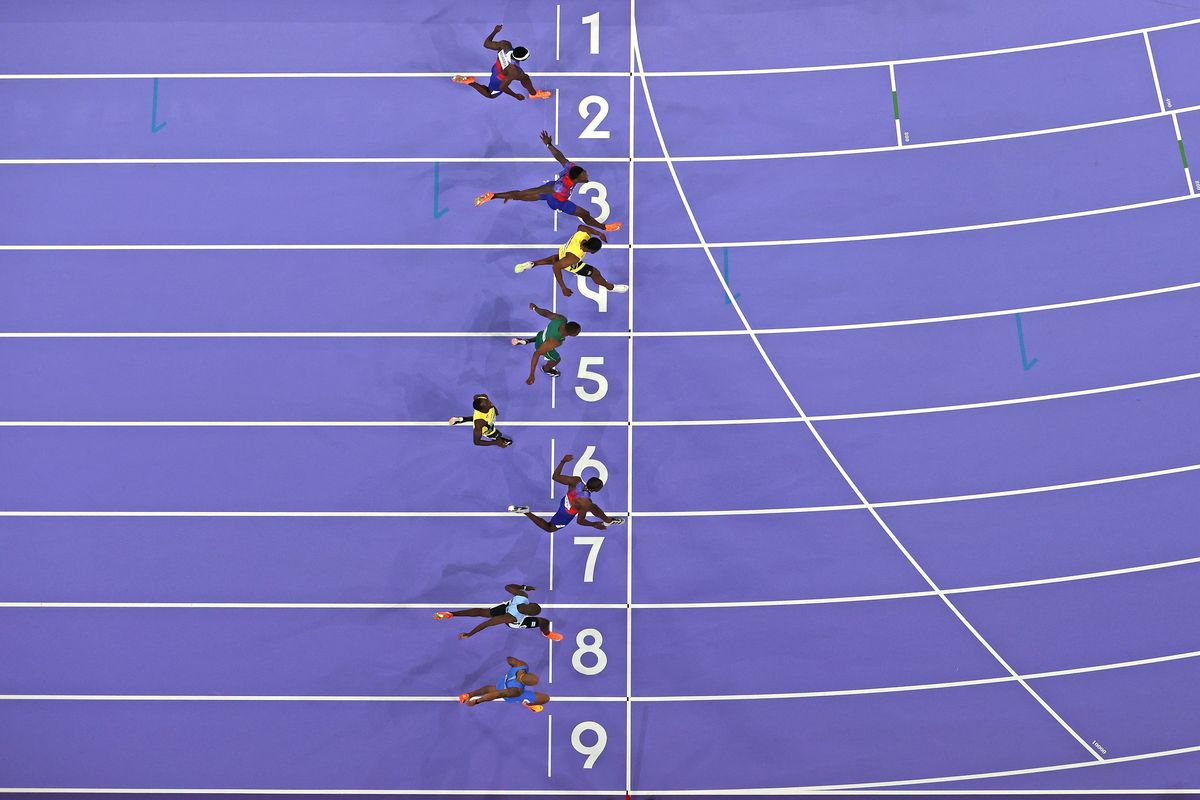

Noah Lyles of Team United States celebrates winning the gold medal after competing the Men's 100m Final on day nine of the Olympic Games Paris 2024 at Stade de France on August 04, 2024 in Paris, France. (Getty Images)

SAINT-DENIS, France – In the days before his greatest moment, Noah Lyles carried with him an emblem of his lowest. As he packed for the Paris Olympics, he stuffed the bronze medal he collected three years earlier into his bag. It was a prize he had won, but it did not feel like a victory. It felt like the byproduct of a difficult year and a battle with something inside of him that he had not yet won.

Lyles brought the bronze with him to Stade de France on Sunday. Just after 11 p.m., after he had won one of the most remarkable races in track and field history, he sat behind a dais in an auditorium and held that bronze aloft. Lyles had long before suppressed his demons and cemented himself at the apex of track and field. But he wanted to remember where it began. The path to becoming the Olympic champion in the 100 meters started in Tokyo.

“I was fueled as soon as I saw this in my hands,” Lyles said, showing the room his Tokyo bronze.

Lyles’ first Olympic gold medal, earned by five-thousandths of a second in a photo finish over hulking Jamaican Kishane Thompson with a personal best of 9.79 seconds, is probably just the start. He has won 27 consecutive 200-meter races, and when the first round begins Monday he will be the overwhelming favorite. Lyles presumably will run the anchor leg of the 4x100 relay. If he performs at or near his peak, he will become the first man since Usain Bolt in 2016 to win three sprint golds at one Olympics. And he could achieve his long-stated goal of elevating track and field in the public consciousness.

He once assumed all of that would happen in Tokyo. Heading into 2020, Lyles had the 200 meters in a stranglehold. His coach, Lance Brauman, planned to use the Olympic buildup to strengthen his start and shrink his 100-meter times. At 22, four years after he made the unprecedented choice to skip college and turn professional out of Alexandria’s T.C. Williams High (now known as Alexandria City), Lyles would inherit the throne Bolt vacated.

The pandemic affected everyone differently, but it decimated Lyles. He loves people and thrives on crowds. He suffered from asthma as a child, and he still takes extra precaution to guard against sickness. He panicked about the uncertainty of the Olympics, which would be postponed by a year. After the murder of George Floyd, he publicly protested the killing of Black men by police and questioned how he fit into America as a young Black man. Always exuberant, Lyles spiraled.

Lyles began taking antidepressants. He believed they affected his training, and he came off them before the U.S. trials in 2021. When he flew to Oregon about 18 months after he made a photo of three gold medals the lock screen on his phone, he wondered whether he would even make the team.

Lyles made it to Tokyo, and the atmosphere plunged him back into strict pandemic protocols. His mother, Keisha Caine Bishop – both his personal rock and his professional manager – could not join him. The empty stadium sapped his energy. When he stood behind his blocks before the 200 final, he thought: “This is not fun. This is not it.” He wound up third, still his worst finish as a professional.

In the bowels of an empty, sweltering stadium on the other side of the world, Lyles bawled in front of reporters. He called the bronze medal “boring.” He said he wished his brother, Josephus, another track standout, had been there instead of him. He shared his struggle with depression in hopes that others would seek help.

“The journey started after 2021,” Lyles said Sunday. “I got to change. I got to evolve.”

When he returned home, he met with his therapist. She told him something that startled him.

“I don’t think you should have won that medal,” she told him.

“Wow,” he replied. “You playing me like that?”

She explained what she meant. Had Lyles won a haul of golds, he would have been bored by the sport. Motivated by disappointment, he would reach his fullest potential. He thought about it and decided she was right.

Three years separated Tokyo and Paris, but Lyles’ transformation was not a long arc. It happened in a matter of weeks. The pressure from the Olympics dissipated. At the urging of Brauman, he traveled to Eugene, for the Prefontaine Classic a few weeks after the Olympics. A roaring crowd made him feel lighter. His brother, also a professional sprinter, raced alongside him. Lyles won the race in 19.51 seconds, at the time the second-best time of his career.

“OK,” Brauman thought. “This is the normal guy back.”

Normalcy and time helped Lyles so much. A switch flipped.

“And then we went into training that next year and haven’t missed a beat,” Brauman said. “He’s special.”

Long before Paris, Lyles had cemented himself atop the track world. He set the American record in the 200 at the 2022 world championships. He won gold in the 100, 200 and 4x100 relay at worlds in 2023. He starred in “Sprint,” the popular Netflix documentary series. He had shown how to ask for help, and he had shown how to use that help to get better.

But the Olympics, he knew well, are how the wider public would judge him. Lyles still thrives on a crowd. Stade de France provided the best any American athlete here has seen. Before Brauman and Lyles parted ways before the final Sunday night, Brauman reminded him, “A showman shows up when the show’s on.”

When the public address introduced him in Lane 7, Lyles bounded some 30 meters down the track, screaming and waving his arms for more noise. As he stood in the blocks in the impossibly tense moments before the starting gun, Lyles mouthed: “Thank you, God. Thank you, God.”

Afterward, he ran to the crowd and found his mother. In his early childhood, Lyles suffered from asthma. His lungs filled with mucous at night with such intensity he often would be rushed to the hospital and hooked up to a nebulizer. At night, Caine Bishop would sleep sitting up, back-to-back with her son, so his lungs could drain.

On Sunday night, that boy sprinted to her, an American flag around his back. He had just become the first American man to win the 100 since Justin Gatlin in 2004, ending the longest drought in U.S. history.

“You’re so blessed, Noah,” Caine Bishop told him. “I’m so glad. I’m so glad. I’m so proud.”

When the race splits were released, they showed Lyles, the champion, had been the slowest of the eight runners out of the blocks. How, he was asked late Sunday night, had he chased down the other seven fastest men in the world?

“To be honest,” Lyles said, “I just believed in myself.”