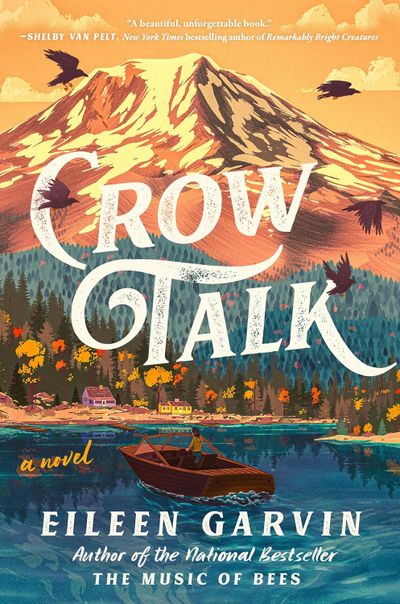

Book review: Crows talk and us humans should listen, says Eileen Garvin’s latest ‘Crow Talk’

Eileen Garvin uses wildlife to comment on the human condition.

As she did with “Music of the Bees,” Garvin deftly uses nature to tell the story of people in her latest novel, “Crow Talk.”

Now, I admit, I started this novel as a skeptical reader. The title at first made me roll my eyes. “Music of the Bees” followed by “Crow Talk.” What’s next, “Dancing with Deer?”

Garvin forced me to, well, eat crow. And I devoured it like a rich dinner on the Las Vegas Strip. “Crow Talk” continues Garvin’s storytelling along the banks of her home in Hood River, Oregon.

Garvin continues to introduces us to characters who some might see as broken but are full of quiet strength.

That’s certainly what we find when graduate students Frankie, Anne and the latter’s 5-year-old son, Aiden, are brought together in the Oregon wilderness of the 1990s.

Frankie O’Neill is an excelling student in the University of Washington avian program. Even with her academic success, she can’t live up to her own family’s expectations. Despite being the pride of her father’s eye, she can’t get past her mother’s steely-eyed disapproval and her milquetoast brother, Patrick. She’s headed to spend time alone at the family’s cabin on fictional Lake June, running away from something.

Anne Ryan is a teacher of the folk music from her native Ireland in Seattle. She’s also mother to Aiden and a disappointment to her socialite in-laws from the wealthy and haughty family of her husband, Tim Magnusen. Aiden is a boy who doesn’t speak and is uncomfortable with the closeness of people. To the Magnusens, Aiden is simply an undisciplined child, and the blame Anne for that.

Her husband, Tim, loves her deeply but doesn’t know how to handle his child. He also doesn’t know how to do anything but agree with his parents.

To get away, the family end up at their own lake house on June Lake.

Garvin’s storytelling evolves mystery and plot twists from everyday occurrences. It’s what makes her stories magical.

She also lets the characters be themselves, without the labels other people may put on them. We know other people see Aiden as different. We know about an assessment being done at the UW pediatrics school that hints at a diagnosis is coming. But rather than letting that drive Aiden’s story, Garvin allows the boy to live his life.

Anne sees Aiden as a growing boy finding himself. Her husband and in-laws see the boy as someone with a problem who needs fixing.

Above it all, there are the crows.

Frankie grew up in the woods in the shadow of Mount Adams, listening to the birds sing and watching their habits, leading to her research studies propelling her towards a doctorate.

She’s especially fascinated by the crows, seen by many as a nuisance, but depicted in fairy tales, folklore and literature as magical.

Crows, we learn, can recognize faces. They know their friends and enemies. They talk to each other and live in communities. They stay put and do not migrate.

Because of Frankie’s unjudging relationship with the birds, she also does not judge Aiden. This helps her form a bond the boy’s parents cannot attain. It leads to a friendship with Anne. They find they have pain in common, both having experienced heartbreaking losses and fighting the disproval of family.

Garvin’s writing power is her empathic approach of giving strength to what some might consider character flaws. Garvin can find power in the fear of broken dreams and the self-doubt of a parent.

The stories behind the crows are based on real research, including that of John Marzluff, a professional of environmental services at the University of Washington. Garvin even includes Dr. Marzluff as a character in the novel.

Garvin combines the myths of popular folklore of the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen and Aesop, as well as science, cited in notes at the end of the book, to help us understand the struggles of Frankie, Anne and Aiden. The birds themselves become living characters in the story.

Garvin makes us aware that the crows are trying to tell us something, if only we are wise enough to listen.