Review: Biography details what ‘Rulebreaker’ Barbara Walters did to get to the top

On May 15, 1953, TV Guide ran a profile of Barbara Walters, young producer of a 15-minute children’s program called “Ask the Camera.”

By the time she died, almost 70 years later, Walters had bypassed or broken down lots of barriers. The first woman to co-host a network morning program, first female co-host of a network evening news program and creator of daytime talk show “The View,” Walters interviewed everyone who was anyone in politics and entertainment and was on a short list of individuals who have had the greatest impact on television news.

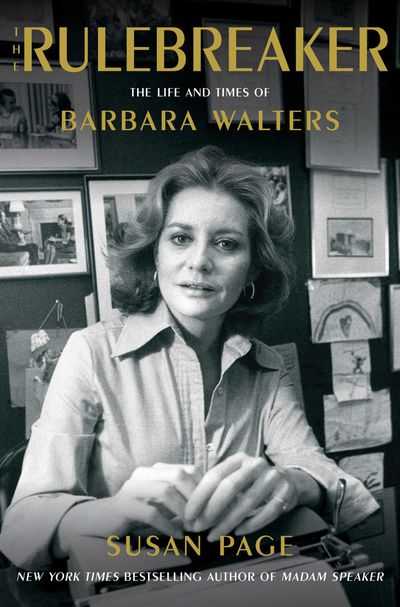

In “The Rulebreaker,” Susan Page (the Washington bureau chief of USA Today also wrote biographies of Barbara Bush and Nancy Pelosi) draws on archival research and more than 120 interviews. She creates an often-riveting account of a smart, demanding, competitive and thin-skinned broadcaster who once confessed that she was doing what she knew “how to do better than anything. Not life, not how to handle life. I don’t know how to do that.”

Page probes Walters’ complicated and conflicted relationships with and decades-long financial support of her father, Lou Walters, a nightclub impresario, who made and lost fortunes; Dena, her often disgruntled mother; Jackie, her special needs sister; and Jacqueline, her adopted daughter. Barbara’s three marriages failed, Page demonstrates, because her career always came first. And Page examines her friendships and romantic attachments with among many others, lawyer and fixer Roy Cohn, U.S. Sen. Edward Brooke, and economist Alan Greenspan.

Most important, Page documents the sexism Walters faced in network newsrooms. Frank McGee, her co-host on NBC’s “Today Show,” we learn, insisted on asking politicians the first three questions and lobbied producers to assign his colleague to “girlie” interviews.

Walters, however, did not call herself a feminist or join colleagues in lobbying for an end to systemic gender discrimination. The path she paved for the women who followed her, Page writes, was, “first and foremost, one that she was cutting for herself.” Her rivalry with Diane Sawyer was an especially nasty example of Walters’ view that getting on-air interviews with A-listers was a zero-sum game.

Page also implies that Walters’ approach to “the get” and the interview itself was gendered. Several public figures, including Fidel Castro, flirted with her.

In sharp contrast to the aggressive, confrontational, “gotcha” style made famous by Mike Wallace, she probed the emotions and motivations of her subjectsc. Audiences loved it, but one critic complained that Walters had turned interviewing into “weepily empathetic kudzu.”

That said, Page emphasizes that Walters inspired generations of girls and women. As a high school student in Virginia, Katie Couric watched her on television and said to herself, “Hey, if my face doesn’t stop a clock … why not?” The first female solo anchor on a network newscast in 2006, Couric thanked Walters for rattling cages “before women were even allowed into the zoo.” Walters, Connie Chung declared, “earned the right to be a diva.”

Walters died in 2022. Her cremated remains were buried next to her parents and sister in Lakeside Memorial Park in Miami.

Page implies her marker, which doesn’t mention familial relationships, is disingenuous.

“No regrets,” it reads. “I had a great life.”