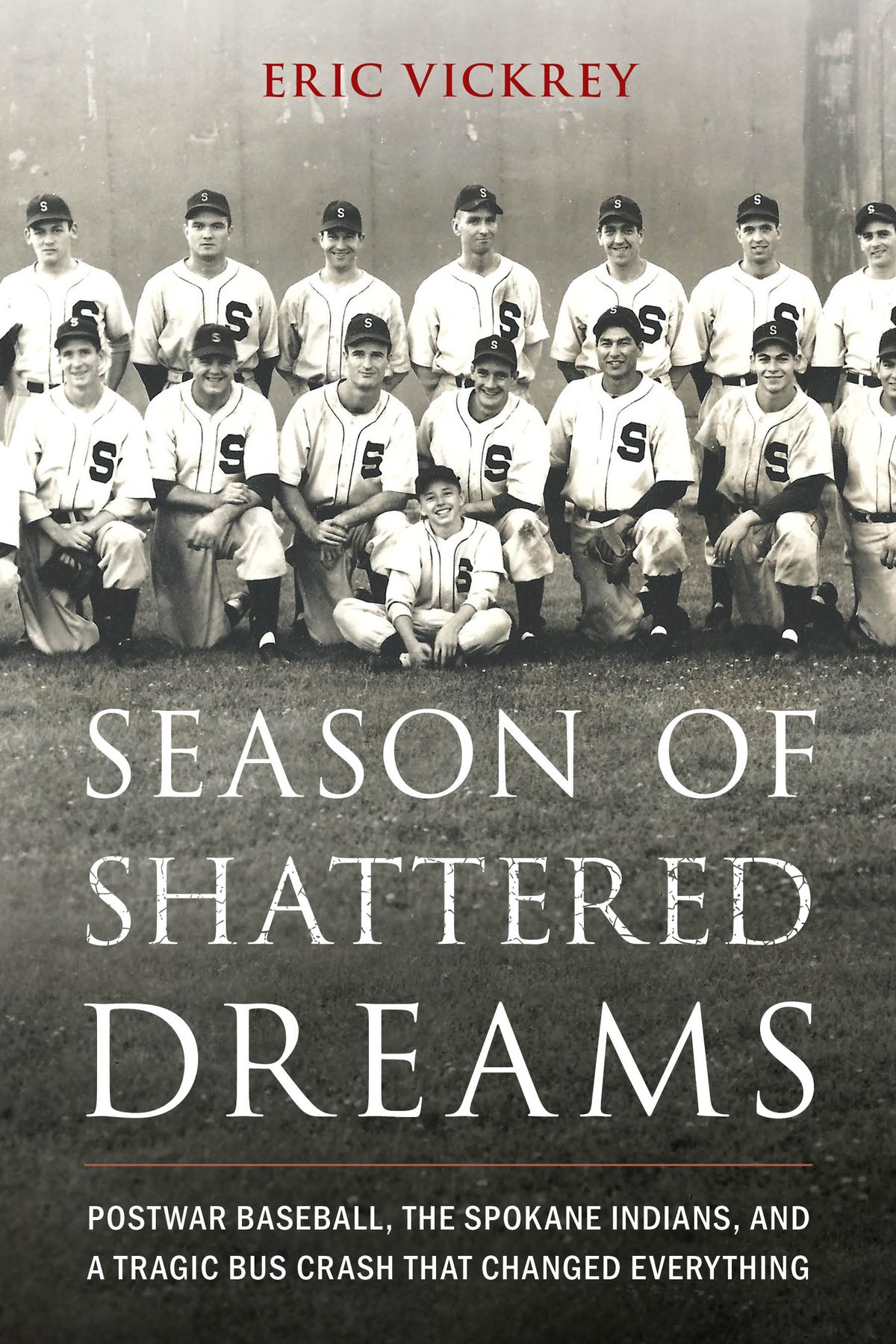

‘Season of Shattered Dreams’ expands baseball players’ stories in 1946 Spokane Indians bus crash

Big league talent spread across the 1946 Spokane Indians baseball team, until lives and dreams were shattered by a bus crash nearly 80 years ago.

That year on June 24, the bus heading to Bremerton, Washington, began descending Snoqualmie Pass on its west side when an oncoming car crossed the center line and clipped it. The bus tumbled off the highway and plummeted into a ravine before bursting into flames.

Among 15 teammates on board, nine players died. Survivors were badly injured. Three members who weren’t on the bus kept memories that never faded.

Those individual players’ stories, along with influences of post-World War II times, captivated Eric Vickrey, author of “Season of Shattered Dreams: Postwar Baseball, the Spokane Indians and a Tragic Bus Crash That Changed Everything.” Its release is Tuesday.

Vickrey, 44, is scheduled to talk about the new book at 11 a.m. Saturday at Auntie’s Bookstore, 402 W. Main Ave. A West Seattle resident, he’s a full-time physician assistant at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, but Vickrey also writes about baseball history as a hobby.

“I’d never heard of the Spokane Indians bus crash until a few years ago when I was actually researching a player who was playing for the Bremerton Bluejackets that year and I came across a newspaper article,” Vickrey said.

“I thought, this is quite a story. I’m surprised I never heard about it. That stuck in the back of my mind.”

Vickrey, a decadeslong Cardinals fan, grew up in Illinois with a love of baseball. He now cheers for the Mariners. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he began writing for the Society for American Baseball Research and later completed his first book: “Runnin’ Redbirds: The World Champion 1982 St. Louis Cardinals,” released in 2023.

He picked up the thread for the Indians book by late 2022, and Vickrey credits groundwork laid by Jim Price, a retired Spokesman-Review sports reporter. Price wrote several articles about the 1946 Indians crash and interviewed survivors in the years later.

The crash’s death toll remains the largest in the history of American professional sports, said Price, who reviewed Vickrey’s manuscript. He also advised on a 2006 book, “Until the End of the Ninth,” set around the tragedy.

“I admire the fact that Eric took this on and was able to succeed, because it is an extraordinary story about an extraordinary team,” Price said.

Vickrey dove into more research, reading Spokesman-Review and Spokane Daily Chronicle archives, while reaching out to surviving relatives of players.

“A couple of the family members still had scrapbooks, which included letters and mementos of players involved in the accident,” Vickrey said. “I was able to gather first-hand accounts of players describing their feelings about everything from their baseball career and their aspirations in the game to what was going on in day-to-day lives.

“I feel like that added a lot to the project, being able to add the voices of those players.”

Vickrey decided to focus on a few players who stood out, including Vic Picetti, the youngest player and a talent at first base.

“He was widely considered by baseball scouts to be the best prospect on the West Coast.”

Picetti, 18 when he died in the crash, had played for Esquire Magazine’s high school All-Star Game in New York. There, he met legends such as Babe Ruth and Mel Ott. All 16 major league teams expressed interest in signing him.

“Ultimately, he signed with the Oakland Oaks,” the author added. “He played for Casey Stengel, the manager who sent him to Spokane so he could gain more experience.”

Picetti likely would have joined baseball greats, he said, but his family story also is painful.

“Vic not only had dreams of playing baseball, but his father had passed away a year before, so he was the sole provider for his mother and two younger siblings.”

The book includes parts about outfielder Bob Paterson, who also died and had big league promise. A family member shared his letters about going pro in baseball.

The life of survivor Jack Lohrke sounds like a Hollywood movie, Vickrey added. He fought in WWII, landed on Normandy a month after D-Day and was in the Battle of the Bulge.

Returning after the war, Lohrke got bumped off a flight from New Jersey to California by a higher-ranking officer, Vickrey said, and that plane had later crashed.

“He had already had multiple brushes with death before the bus crash,” Vickrey said. “He was pulled off the bus in Ellensburg when he found out he was being called up by the San Diego Padres, then he hitchhiked back to Spokane while the rest of his teammates carried on.”

Lohrke went on to play for the New York Giants and Philadelphia Phillies, but an early nickname made him uncomfortable.

“After his close call with the Spokane Indians bus crash, it was shortly thereafter he was given the nickname, Lucky, and that stuck with him the rest of his life,” Vickrey added. “He often said he wasn’t comfortable with that nickname; I think because it was a reminder of his fellow soldiers and teammates who were not so lucky.”

Survivor Ben Geraghty aspired to be a baseball manager and had played before the war for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He briefly managed the Indians, then eventually held that role for the Milwaukee Braves’ farm team in Jacksonville, Florida, when Hank Aaron played for him. Aaron often credited Geraghty’s influence, Vickrey said.

“Aaron always said that Geraghty played a pivotal role in helping him navigate that difficult season in the Jim Crow South,” Vickrey said. “Aaron always called Geraghty the best manager he ever played for. He thought Geraghty should have been given a shot at managing for the major leagues.

“What ultimately happened was Ben had fear of bus travel, so kind of the way he coped with that was by drinking alcohol. His heavy drinking ultimately had negative consequences on his health, may have been what prevented him from managing in the major leagues and probably contributed to his early death at the age of 50.”

After the crash, the Indian’s roster was filled in from other organizations. Two Indians players who had driven separately, Milt Cadinha and Joe Faria, stayed on the team. Pitcher Gus Hallbourg returned after recovering from injuries. Until his 2007 death at age 87, he was the last survivor still alive.

The close-knit 1946 team had a good shot at winning that year’s league pennant, Vickrey said. After the accident, the reframed group finished seventh out of eight teams.

Vickrey’s book includes postwar factors, when baseball saw an influx of players returning from military duty.

The U.S. struggled with inflation, poor infrastructure and lack of materials. The charter bus had its own troubles. Driver Glen Berg had complained of brake and engine trouble.

“A lot of talented players from the New York Yankees and two Pacific Coast League teams ended up in Spokane that summer. My goal with this book was really to tell the stories of the players who lost their lives, and also the impact that the crash had on the survivors. It had ripple effects through families and across future generations.”