NASA budget woes could doom $2 billion Chandra space telescope

NASA spent $2.2 billion to build and launch the Chandra X-Ray Observatory in 1999, and it has performed brilliantly, scrutinizing deep space, black holes, galaxy clusters and the remnants of exploded stars. It sees things that other space telescopes can’t see, because it literally has X-ray vision.

It also has some old-age problems. Without careful planning, it can overheat, apparently because the reflective insulation on the telescope isn’t as shiny as it used to be. That’s just an educated guess – for 25 years it has been orbiting Earth, and no one has had a close look, much less touched it with human hands. But Chandra continues to be a scientific workhorse, delivering otherwise unobtainable views of the cosmos.

Chandra’s future, unfortunately for the astronomers who love it, is gloomy. If Congress approves the Biden administration’s 2025 budget request for NASA science missions, they say, the Chandra mission will be effectively terminated.

The old telescope’s uncertain status is part of an acute budgetary problem at NASA’s science mission directorate. There’s not nearly enough money for all the planetary probes, Mars rovers and space telescopes already built or on the drawing board. And officials have made clear to everyone that additional money is not likely to descend magically from the heavens.

The taxpayers do provide resources, including about $7.5 billion per year for NASA science missions. But the budgets haven’t been able to keep up with the scientific ambitions, including costly attempts to retrieve samples from Mars.

NASA’s strategic vision can also be swayed by competition from abroad. China and other nations are launching spaceships right and left. China could put astronauts on the moon in just a few years. There is talk in military and national security communities about the “Space Race 2.0,” and of space as a war-fighting domain.

In tight budgetary times, there are winners and losers. Chandra could be just one of several missions in the latter category.

NASA does not say it is killing the Chandra mission. But the language in the March 11 NASA budget request did not sound promising: “The reduction to Chandra will start orderly mission drawdown to minimal operations.”

The telescope has been funded at a little under $70 million per year, but the fiscal 2025 budget request cuts that to $41 million, then to $26.6 million the following year, dropping all the way to $5 million in fiscal 2029.

“We had to make some tough choices in order to keep a balanced portfolio across the science mission directorate,” NASA’s top science administrator, Nicola “Nicky” Fox, said. “Chandra’s very, very precious … but sadly, it is an older spacecraft.”

Flat budgets vs. lofty ambitions

Last spring, after a rancorous budget battle on Capitol Hill, President Biden signed the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which raised the federal debt ceiling but required limits on federal spending. Across much of the government, agencies are coping with flat budgets, at best, even as inflation makes everything more expensive.

Casey Dreier, chief of space policy for the Planetary Society, wrote in a recent column that even with a 2% bump in NASA’s overall budget in the 2025 White House request, it still represents a $2 billion loss in buying power since 2020 due to inflation.

With the Artemis program, the United States is fully committed to putting astronauts on the moon again. The Artemis mission includes lunar science. But the bulk of the dollars are going to rockets, spaceships, orbital refueling stations, lunar landers and the complexities of keeping human beings alive on a place that lacks the comforts of home, such as air.

And then there is Mars Sample Return. It is NASA’s most ambitious and costly planetary science program. It aims to haul pieces of Martian soil back to Earth for laboratory research, a priority of the scientific community, which suspects that in its warmer and wetter youth the Red Planet was an abode of life. The Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in 2021, has already dug up and stashed the samples.

But getting them to Earth will not be easy or cheap. An Independent Review Board last year said the mission was on track to go over budget and would fail to meet the launch schedule. The reviewers estimated that sample return would cost between $8.4 billion and $10.9 billion over the lifetime of the mission.

NASA responded by creating a team to review the architecture and timeline of the mission. For months, Mars Sample Return has been in limbo, but that difficult period could be about to end: On Monday, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and Fox will hold a teleconference with reporters to announce the results of the mission review, with a NASA town hall to follow.

In the meantime, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which is managing the mission, laid off about 8 percent of its workforce.

An X-ray underdog

Across the science community, people are advocating for their missions, meeting with lawmakers on the Hill, trying to explain why research that might seem esoteric to the general public deserves support.

And there are some hard conversations within the science community about which missions are worth the investment in a time of limited resources. The costliest “flagship” missions often threaten to eat the lunch of the smaller missions. And although the Webb telescope has been a great success, it came at a cost of roughly $10 billion and was slapped with the memorable tag of “the telescope that ate astronomy.”

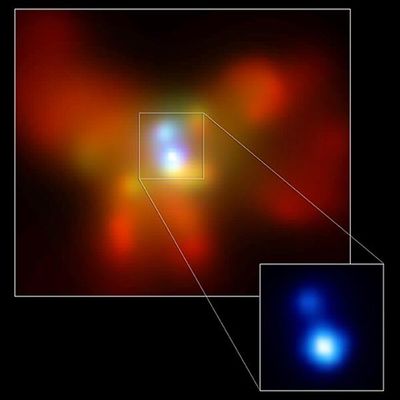

As an X-ray telescope, Chandra is not as versatile as the Hubble or Webb space telescopes when it comes to producing poster-worthy images, so it doesn’t have the celebrity status of those observatories. But it has racked up a long list of discoveries, some in collaboration with telescopes that observe in different wavelengths. In 2015 Chandra observations captured a black hole shredding a star. In November, Chandra observations were key to the discovery of a supermassive black hole in a galaxy 13 billion light-years away, claimed as the oldest, most distant black hole of its kind ever seen.

If Chandra is reduced to minimal operations, about 80 people are expected to lose their jobs.

“I started working on Chandra straight out of graduate school in 1988. It’s been my entire career,” said a wistful Pat Slane, 68, the director of the Chandra X-ray Center in Cambridge, Mass.

“We just received proposals last week for next year’s observations for Chandra, and we were oversubscribed by a factor of five,” Slane said. “We will make the case that it’s still a viable observatory.”

Grant Tremblay, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, is among the scientists advocating for Chandra’s survival. The demise of the telescope won’t end X-ray astronomy, but the United States will lose its status as the leader in the field, he said.

“I’m rooting for scientists all around the world. I don’t care what flag they carry,” Tremblay said. “But it is true that the U.S. will cede leadership in cosmic discovery.”