Wheat Country forecast: Specter of wind turbines divides the Palouse

One of Triple Oak Power's meteorological towers off Denny Station Road southeast of Davenport. The company is using the tower to take wind measurements to determine the best positioning for wind turbines for the Great Bend Wind Project. (James Hanlon/The Spokesman-Review)

HARRINGTON, Wash. – Several energy companies are exploring major wind projects in Eastern Washington. Just don’t call them wind farms, or else some wheat farmers might take offense.

The companies are buying up leases from landowners across Lincoln, Whitman and southern Spokane counties – to the chagrin of some neighbors who want to preserve the rural skyline.

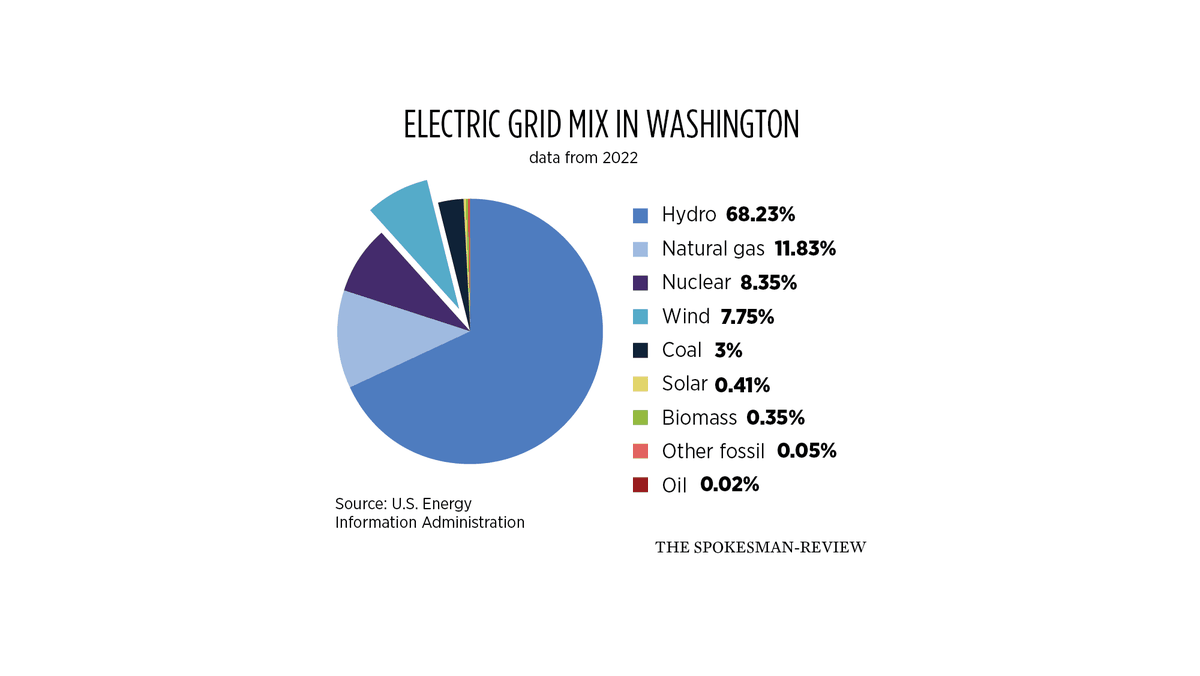

The developments are still in the exploratory phase, but together they could produce over 1,000 megawatts from hundreds of turbines and bolster Washington’s goal of reaching 100% clean energy by 2045.

Exact boundaries of each project will depend on wind conditions, setback requirements and what land they are able to piece together.

In Lincoln County, Triple Oak Power is exploring an area between Davenport and Reardan north and south of Highway 2 that would be called the Great Bend Wind Project.

The Portland-based company has leased 17,000 acres and is in discussion for at least another 8,000, CEO Jesse Gronner said. Triple Oak aims to install 60-100 turbines.

Triple Oak has also installed three meteorological towers in the area. Just shy of 200 feet tall, the temporary towers will collect data on wind speed and direction to help determine the best configuration for the turbines. Gronner said they need to take at least two years of measurements to compare four-season cycles.

Gronner told the Lincoln County Commissioners in a presentation Monday the project is in early stages and there is no proposal yet.

“These things take years,” Gronner said. There is enough wind resource and landowner interest to move forward with developing the project, he said.

Scott Hutsell, chair of the Lincoln County Commissioners, said some constituents think the county has the ability to block the projects.

“We can’t tell people what to do with their personal property,” Hutsell said. They can, however, regulate certain parameters.

The planning commission is working on a zoning code update for wind and solar facilities that could establish requirements for windmills to be placed a certain distance from roads and residences.

“A lot of people don’t want it in their back yard,” Hutsell said. “But the next guy has extra property, would love to do this. There’s a lot of money in it.”

Tenaska, an Omaha, Nebraska-based energy company, is developing several projects in the area for a Canadian company called Cordelio Power, which would sell the electricity to local utilities. Tenaska is searching west of Harrington south to the Adams County line and another area that overlaps with Triple Oak’s Great Bend project.

Gronner said the companies are aware of each other, but have no partnership plans at this stage.

Tenaska is also investigating southern Spokane County.

Commercial wind facilities are not allowed in Spokane County’s zoning code. A wind company would need to apply for a text amendment to be reviewed by the planning commission, said Martee Snyder, associate planner for Spokane County land use.

The next opportunity for a review is fall 2025, and the process takes about a year, Snyder said. Once an amendment is adopted, wind companies would still need to apply for a conditional use permit, which would go through public comment.

Farther south in Whitman County, Steelhead Americas is developing Harvest Hills Wind Project, a 25,000-acre area between Colfax and Palouse. Steelhead is the North American development arm of Vestas Wind Systems, a Danish wind turbine manufacturer.

The project plans to generate 200 megawatts from 45 turbines by 2026.

Shane Roche, Vestas development manager, said the actual impact would only take up about 45 acres, since each turbine requires about an acre for the foundation and turnaround area for service trucks. That leaves plenty of room for landowners to continue farming.

Steelhead has three meteorological towers in the area and has collected 1½ years of data . Roche said the consistent breeze and access to transmission lines make the area a good fit.

The project needs to complete an environmental assessment and a final permit from the county, but could begin construction as early as this fall.

Lease terms are 30 years. After that, they could be renewed, or the turbines would be removed. The county ordinance requires the company to pay a security deposit up front to cover the cost of decommissioning.

A local opposition group worries this project will ruin the view of Kamiak Butte, a county park recognized as a National Natural Landmark. A Change.org petition to stop the project has more than 1,200 signatures.

For comparison, the closest existing wind facility in the area is the Palouse Wind Farm, owned by Onward Energy, which generates about 104 megawatts from 58 turbines near Oakesdale. The electricity is sold to Avista Utilities and is enough to power 30,000 homes.

Oakesdale Mayor Dennis Palmer said he hasn’t heard any complaints about the project since it was built 12 years ago. Noise hasn’t been a problem, he said.

Renewable energy projects can apply for a site certification agreement through the Washington Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council, which has siting authority with approval from the governor.

Local objections, including some by the Yakama Nation, over threats to ferruginous hawks and interference to fighting wildfire from the air, have delayed and reduced the size of what could become Washington’s largest wind facility, Horse Heaven Hills Wind Farm near Tri-Cities.

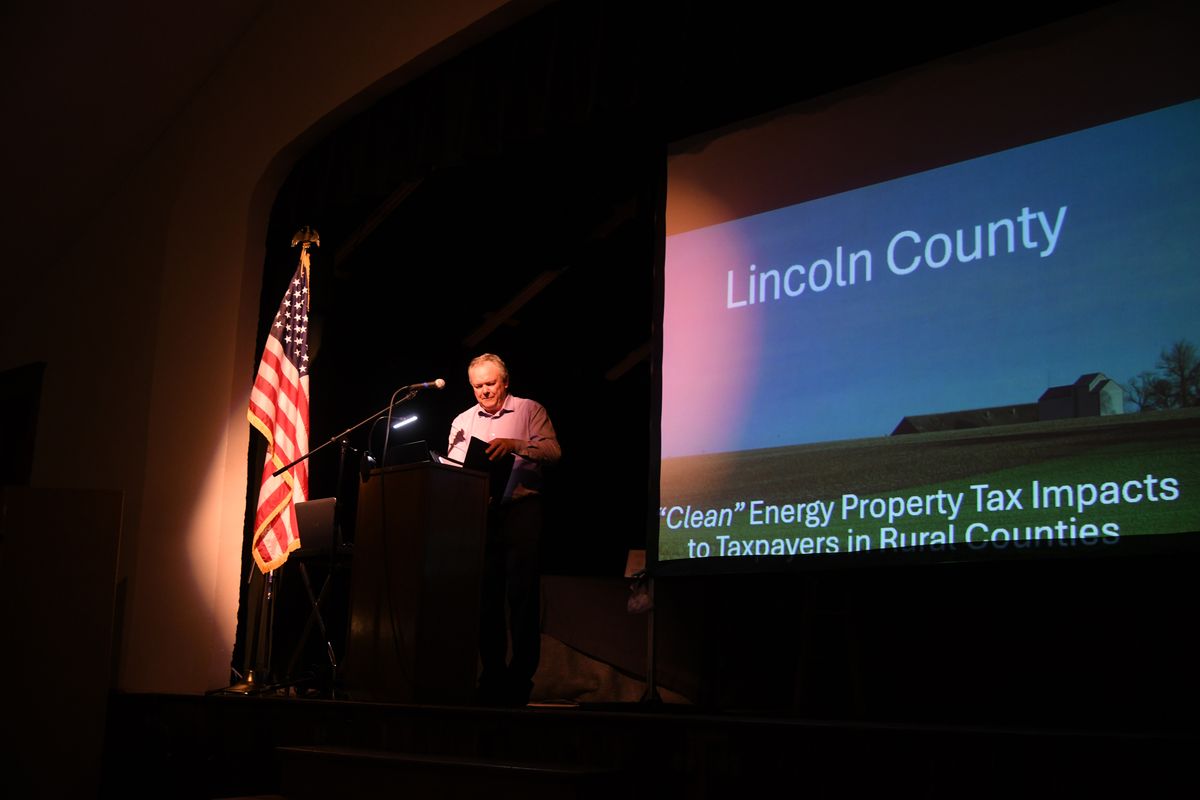

Another opposition group called Save the Lincoln County Skyline organized a community meeting that filled the Harrington Opera House late last month.

Speakers and those in attendance worried about windmills killing birds and bats, lower property values and simple distaste for windmills as an eyesore on the landscape, while espousing doubts about climate change.

David Boleneus, a retired geologist, gave a 40-minute talk on supposed health effects from low sound frequencies.

Others speculated the push for wind is to justify replacing another form of renewable energy: hydroelectric dams from the Columbia and Snake rivers.

“I personally believe that the whole what I call ‘dirty green energy revolution’ is one of the biggest scams ever perpetrated on the American people,” Lincoln County Commissioner Rob Coffman said, pointing to what he called hypocrisy by those supporting renewable energy for allegedly ignoring child labor and environmental damage in extracting materials to build turbines and electric vehicles.

On the other hand, Coffman said he is a proponent of property rights.

In an interview, Brian G. Henning, director of the Gonzaga Institute for Climate, Water, and the Environment, said it is important in these conversations to ask, “Compared to what?”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates land-based wind turbines kill about 230,000 birds a year, which is small compared to 600 million birds estimated to be killed by building glass or 215 million killed by vehicles.

“People assume that to do something different than the status quo, the impact has to be zero,” Henning said. “But a better question is, is it better than what we are doing today?”

It is worth paying attention to the harms from producing wind turbines, Henning said, but again, these are low compared to other forms of energy. Fossil fuel extraction also displaces habitat, and its pollution kills humans and animals.

Henning said he hasn’t seen any good evidence to support claims about health effects from sound.

Aesthetic complaints are fair and should be part of the conversation, Henning said, yet they are impossible to quantify since it is subjective. Open-pit coal mines are ugly too, Henning said.

In a presentation on local tax implications at the Harrington meeting, Coffman said the county would benefit from a large tax increase from the wind companies at first, but a quirk in Washington’s personal property tax law would shift the burden onto existing taxpayers over time. As the turbines depreciate, the wind companies would pay less property tax every year, but the new baseline would remain and increase tax for the rest of the district to make up the difference.

A recent report by the Washington State Association of Counties shares Coffman’s concern. Examples from other counties show that over half of the property tax for renewable projects can depreciate over 10 years, amounting to millions of dollars.

Gronner, the Triple Oak CEO, said he is open to working with the county and discussing reforms to the tax code in Olympia.

In the meantime, the issue is dividing neighbors.

Jason Bishop, a fifth-generation wheat farmer near Edwall, was approached by one of the companies with a lease proposal, and he’s conflicted.

“It’s tempting because the price of wheat is so low right now, Bishop said. “It wouldn’t have been such a tough choice two years ago.”

After the Harrington meeting, Bishop said he has a lot to think about. He is weighing the relationship with his neighbors, as well as consequences for the legacy of his family farm. He wonders what his great-grandparents might have done.

“This is a major decision,” Bishop said.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that wind facilities are required to have approval from the Washington Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council. Renewable energy projects can opt to apply for a site certification agreement through the council in lieu of applying through the county.