With no room for asylum seekers, Washington state church turns away families

Asylum seeker Lina Ines Zacarias, from Angola, sits in a large room Monday at Riverton Park United Methodist Church in Tukwila. She is due to give birth in two weeks and has two older children who were in school at the time. The family has been in the country for five weeks. (Ellen M. Banner/The Seattle Times/TNS)

As hundreds of asylum-seekers faced the threat of sleeping outside Tuesday night, King County’s asylum-seeker crisis reached a new, more serious stage.

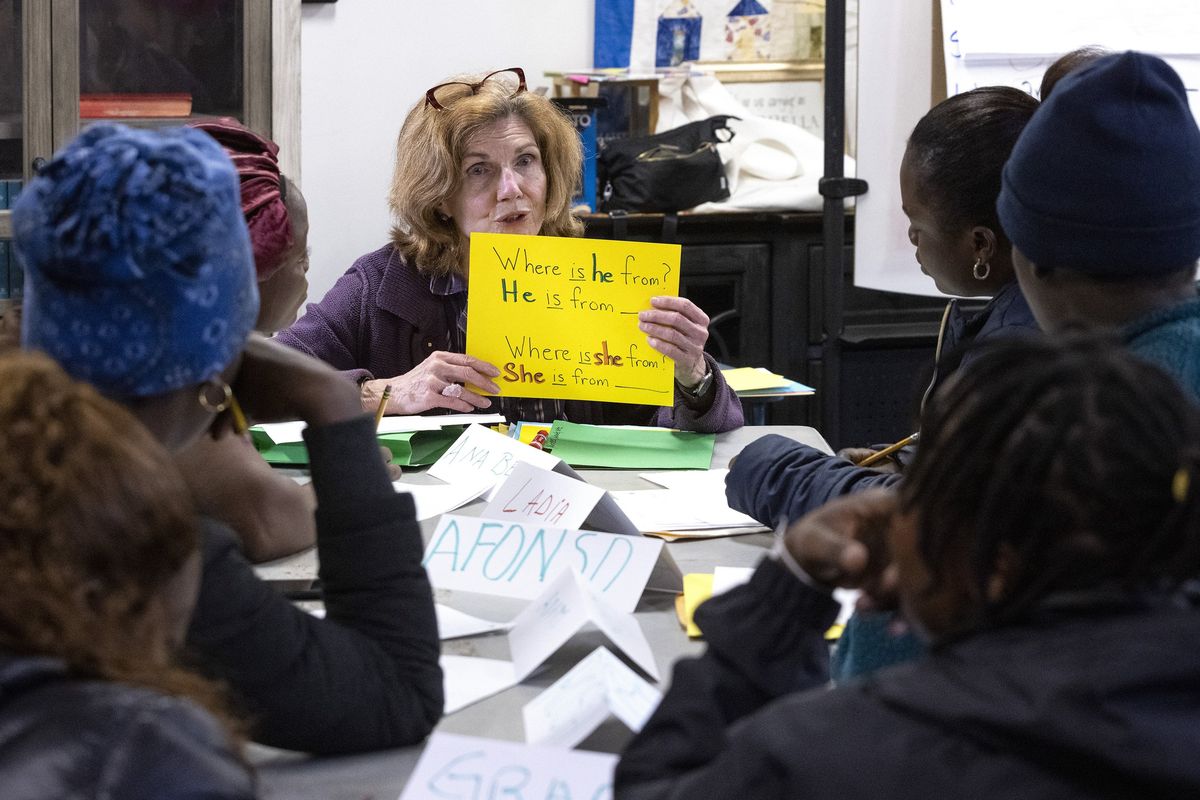

For the last sixteen months – since this crisis began – Tukwila’s Riverton Park United Methodist Church has consistently provided shelter to families seeking asylum in King County when no one else has. Until now.

Starting two weeks ago, Pastor Jan Bolerjack, head of the church, began turning families away, even families with young children, because the church’s interior and surrounding grounds are at capacity, she said.

“We are over capacity,” Bolerjack said Monday. “We have people sleeping in every corner that we could find.”

Additionally, hundreds of asylum-seekers who have been living in private rentals and at the Kent Quality Inn Hotel are facing the threat of sleeping outside, many with children, as donations to cover their stays have run out.

On Tuesday morning, around 100 people facing eviction attended King County’s Health and Human Services Committee meeting to demand that someone take action to help provide temporary housing. One of the group leaders, Adriana Medina, said those without a place to stay are gathering supplies to sleep in a Seattle city park if other housing does not materialize.

“There’s no other option,” she said, standing a block away from the King County Courthouse Tuesday.

The recent surge in asylum-seekers – more than 1,000 people have registered with the Tukwila church since April of last year – has created a great need for temporary housing. Asylum-seekers can’t legally work and earn money to pay for housing while they wait months for the federal government to approve work permits.

So far, local government leaders have not offered immediate solutions to fill the gaps. In the meantime, more and more families are likely to become dispersed across the county without a safe place to sleep at night.

Most officials have pointed to more than $32 million in state funding, included in the new adjusted state operating budget signed by Gov. Jay Inslee last week, as a potential solution. But the vast majority of that funding will not be available for three months.

“The city of Seattle understands the urgency and severity of housing needs for the migrant individuals and families who are staying in Kent,” said Rodha Sheikh, finance and operations manager for the Seattle Office of Immigrant and Refugee Affairs.

“We urge the group to work with the state of Washington, who have the authority and resources to address this ongoing humanitarian need,” Sheikh added.

At the same time, the state Office of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance said state funding is unavailable to cover extended housing costs for now.

“Unfortunately, state funding to support this work is not available until July 1, 2024,” said Sarah Peterson, head of the state Office of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance. That’s because the state Legislature allocated most of it for next year’s fiscal budget, which begins July 1.

Meanwhile, more and more families are arriving at Bolerjack’s door, pleading for help.

“So today, I’ve already told 10 people that they need to leave,” Bolerjack said from a small room lined with books that functions both as the church’s library and as sleeping quarters for about seven people. There are mattresses stacked in the corner and belongings stashed on chairs.

“They just looked at me like, ‘Where am I going to go?’ And I say, ‘I don’t know, but you can’t stay here,’” Bolerjack said.

She estimates more than 300 people are living on church property now. It’s not the most people they’ve ever held. Around 500 people lived on the property in December, but many lived outside in individual camping tents. And that arrangement has since changed.

It started when emergency winter weather hit the region in January, forcing hundreds sleeping in tents outside to seek temporary refuge in hotels. Many never returned to the church and have spread across South King County hotels and private rentals.

By the end of February, the city of Tukwila announced it would set up a large, industrial-strength tent to provide a better shelter alternative for the families living outside.

It was a welcome addition, Bolerjack said. But part of the church’s agreement with the city was that once the industrial tent went up, the church wouldn’t continue to add more individual camping tents on the property, she explained.

“At this time, the city remains focused on working with the church to maintain healthy, safe and more sustainable conditions on-site. A large component of this is limiting the number of people on church property,” said Brad Harwood, spokesperson for the city of Tukwila.

Tukwila, home to about 20,000 people, estimates that by the end of 2024, the city will have spent at least $1.4 million on the crisis.

Without better options to offer, Bolerjack said she’s advised some families to return to the SeaTac Airport, where they first arrived, to sleep because it’s safe and warm. But a spokesperson for the aiarport, Perry Cooper, said only people with “airport business” are allowed to sleep at the airport. And people could be arrested for trespassing charges if they don’t leave.

Families that show up at the Tukwila church are also connected to King County’s family emergency shelter line, Bolerjack said.

Nonprofits Mary’s Place and the Low Income Housing Institute have been providing shelter to some asylum-seekers when space becomes available, but it’s limited and not enough to meet the current need.

An average of 40 to 50 families call the intake line daily, and only two or three are able to receive a shelter bed, said Linda Mitchell, Mary’s Place spokesperson.

During Tuesday’s King County Health and Human Services Committee meeting, one woman told the committee, through an interpreter, that those seeking housing aren’t singling out King County when asking for help. She said she’s tried the resource phone numbers she’s been given, without success.

“We are actually calling several places,” she said. “We are actually trying.”

Last month, Metropolitan King County Council members worked to find local funding to extend the stay for people living in the Kent Quality Inn. More than 240 people were estimated to be facing eviction from the hotel on Tuesday, according to a press announcement released by a mutual aid group.

Councilmember Sarah Perry was able to secure enough funding from two faith organizations, the Muslim Association of Puget Sound and Plymouth Church Seattle United Church of Christ, to cover the group’s hotel stay for a month.

This time, Metropolitan King County Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda said she’s reached out to several places including the city of Seattle, King County Executive Dow Constantine’s office, the King County Regional Homelessness Authority and more.

“We should see this as a call for all of our jurisdictions to work on a triage plan,” Mosqueda said.

As of Tuesday night, no solutions had materialized.