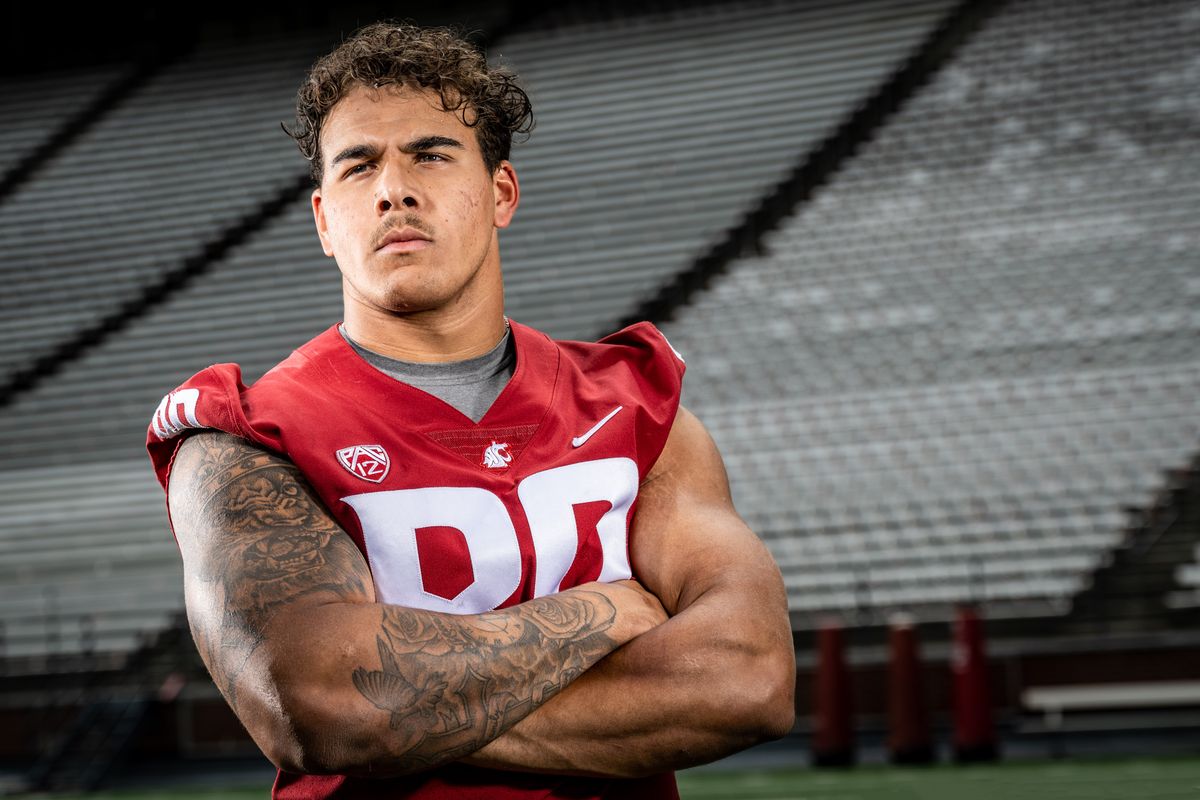

Washington State edge Brennan Jackson won’t let you outgrow him — or outwork him

Washington State edge rusher Brennan Jackson scored a touchdown on a fumble recovery during last Saturday’s upset of Wisconsin. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)

PULLMAN — Brennan Jackson had never been so happy to see someone make fun of him.

Washington State’s star edge rusher was one of the hosts for the official visit of quarterback prospect John Mateer, and even back on this weekend in January 2022, Jackson had ascended to the top of the program. He had just broken out the season prior, earning all-conference honorable mention honors, racking up four sacks, leading the Cougars to their first Apple Cup win over rival Washington in a decade.

In other words, Jackson was one of the head honchos on the team. He was a captain, a star, a 6-foot-4, 260-pound hulk of a guy. No one should have dared poke fun at him, not someone who had just met him, and especially not someone who might be lockering near him in the near future.

Except that’s when Mateer took on the challenge, ribbing Jackson over something small.

“And I just laugh and I’m like, dude, you already get it,” Jackson said. “Like, I’m not someone to be feared in the locker room, per se. I’m really just a goofy dude. I don’t mind it. I’m really comfortable with who I am because at the end of the day, if you try and conform to what other people want you to be like, then you’re never gonna really live your own life.

“So for me, I will always be goofy. I will always say things that aren’t funny that I think are funny. I’ll laugh at it. I’ll always wear my Vans that everyone tells me to get rid of. I don’t care about that. That’s who I am.”

There’s nobody better at capturing Jackson than Jackson himself, which might be his superpower. He knows who he is. He’s comfortable in his own skin. He didn’t mind when Mateer needled him back then, and he doesn’t care when anyone does it now, because he understands himself better than anyone else ever could.

Who is he, then?

“BJ is loose and fun,” WSU head coach Jake Dickert said, “and can really handle his own in a social setting just as much as anybody else.”

“He really moves to his own drum, man,” said Herschel Ramirez, Jackson’s defensive coordinator at Great Oak High in Temecula, California, his hometown.

“He’s always had the ability to laugh at himself or make fun of himself,” said Travis Jackson, Brennan’s dad. “He just likes being around people. He likes other people. He just likes making people happy.”

To understand the other part of Jackson’s makeup, though, we have to revisit the third quarter of Washington State’s upset over Wisconsin last weekend. About an hour after fellow edge Ron Stone Jr. strip-sacked Badger quarterback Tanner Mordecai and Jackson fell on the fumble in the end zone, good for his first touchdown since high school, the visitors had come all the way back — well, almost.

Mordecai had just lasered a touchdown pass, helping the Badgers draw within 24-22, and they lined up to go for two and tie it up. Jackson lined up on the edge, same as he always does. That’s when he looked up and saw Mordecai point at him, and when Jackson read his lips, he understood the directions Mordecai was giving his offense.

Read 80.

“I’m like, ha,” Jackson said. “You messed up, bud.”

Mordecai messed up the second he snapped the ball. He darted to his right, Jackson’s side, where he pitched it to running back Chez Mellusi on a speed option. Jackson tracked Mellusi down and wrestled him to the ground at the line of scrimmage. He waved his arms in front of him, as if to say no way. The Badgers never scored again.

“It’s, tell me I can’t do something, and I’m gonna show you that I can,” said Amy Jackson, Brennan’s mom. “He’s always had that mentality.”

Maybe so, but to become a face of Washington State’s program, Jackson had to take that to the extreme — with a smile on his face.

***

Jeff Maclean couldn’t conceal his smile. Jackson and his classmates had just played their year-end video for Maclean, their AP Chemistry teacher at Great Oak, and they had included a blooper section toward the end of the video.

In the video that got them an A, where Jackson and two classmates sing a goofy song to help them remember the tenets of equilibrium, Jackson sinks a 3-pointer at a local park. In the bloopers, he clanks about 20 beforehand.

“So whenever I see him now,” Maclean said, “I laugh and I go, there’s our 3-point shooter.”

For every story about Jackson obsessing over his football career in college, there’s about a dozen like these, the ones that explain why Jackson had no problem showing his classmates that his jumper needs work.

These days, Jackson finds it easy to laugh at himself. Earlier in his life, he had no choice. Throughout middle and high school, Jackson was about a year younger than his classmates, and when you’re in middle school, laughing at your younger peers might as well be in the school handbook.

Back then, Jackson explained, he didn’t always feel as confident in himself. Sometimes he would feel hurt by some of the jokes, but the more they saw him show it, the more his classmates would laugh.

“So he’s like, I’m just gonna go out and laugh it off, because I’m kind of a goofball,” Amy said. “I’m just gonna go ahead and accept the fact that sometimes I’m a goofball. If you can’t laugh at yourself, who can you laugh at?”

Which is exactly why Jackson is an open book about every funny story from his past. There’s the time when he was a WSU freshman and he arrived on campus wearing fake glasses, the kind with transparent lenses that don’t actually enhance your vision. He got them as reading glasses, but as he began a new chapter in his life, he figured it was time to switch up his look.

“That was a pretty odd era of my life,” Jackson laughed. “I’m glad that it’s over.”

Then there’s the time when, the day of a high school bowl game in Arizona, Jackson slipped on a bag in the hotel room and hit his head. He couldn’t play in the game. “And we had driven to Arizona for this one game,” Amy said. “He didn’t even get to play in it. He would do stuff like that all the time.”

There’s the time when, during a break in a Pop Warner game, Jackson slipped on a metal barrier and split his knee open. There’s the time when Jackson was late getting ready and had to run after Amy’s car because she had left for school without him, like she had warned him she would. The list goes on and on.

Bring any of these up to Jackson now, though, and he wouldn’t try to change the subject. He’d smile and offer even more embarrassing details. That’s the thing, though: He isn’t embarrassed by any of it. He knows he isn’t who he used to be, and he likes who he’s become, so why not chuckle about it?

“When I go on Twitter, I’ll see negative things, but that doesn’t bother me because it’s like, you don’t know me as a person,” Jackson said. “Even if you’re saying negative things about me, I only care about the ones from the people closest to me because those are going to come in a different context and come in a different tone, because they’re trying to actually make me better.”

So much of the reason Jackson likes who he is now, though, is because he made himself better.

***

By now, Jackson’s trainers might have given up on reeling him in. He’ll finish up a grueling lift, where he cranked out a bunch of reps, so they’ll encourage him to take it easy the next day. Maybe rest a little bit.

“But I think they understand with me,” Jackson said, “that feeling of having to put in as much work as possible, that’s what made me into who I am. So I can’t get rid of that.”

Take one look at Jackson, with biceps the size of dinner plates and legs bigger than saucepans, and you understand how deeply he means he’s obsessed: With lifting more than he did yesterday, with developing as a person better than he did yesterday, with treating every down of football like he may never get the chance to play again.

Mostly, that’s because earlier in his career, there was a chance he never would. He tore his ACL in 2018, his freshman season. A year later, he recovered and felt the excitement flood through his body. He was on the travel squad, which meant he was set to travel to Texas, where the Cougars were ready to square off with Houston.

Jackson broke his foot that week in practice. He never made the trip. Later in the week, as his healthy comrades boarded a plane bound for Houston, Jackson dialed his mom’s number in his phone.

“Mom,” Brennan said, “I don’t know if I can do this again.”

“And I’m like, ‘can’t’ is not a word that we use,” Amy replied. “It’s will you or won’t you? It’s not can or can’t. It’s will you or won’t you? You either will or you won’t. That’s different. I know you can, but will you? That’s the question you need to ask yourself.”

Brennan Jackson of 2023 might have felt fired up by the challenge. Brennan Jackson of 2019 had to think about it. Back then, as many across the nation do, WSU coaches cast Jackson to the backburner. They had practices to plan for, games to prepare for, and if you’re injured, well, you aren’t a part of those.

“I was in a pretty dark place for a little bit,” Jackson said.

“He wasn’t used to being put off to the side,” Amy said.

Two months later, Jackson did more than slink to the side. He flew home to Temecula because the coronavirus pandemic had just shuttered the world. There, he thought about things: About his place on the Cougs’ team, about what he wanted out of his next season.

That’s about when Jackson started to hear the noise, the pressure, the concerns of coaches and teammates and fans.

“I think some people doubted him that when he came back from the second injury, was he going to lose it? Was he going to be buried on the depth chart?” Amy said. “Because now this is a guy that’s had two injuries. I think for him, he was just like, I’m gonna go all in, and if I fail, then I fail. But I can’t look myself in the mirror and say, ‘I gave it 99%,’ and be OK with that.”

“I don’t want anybody to be able to look at me,” Jackson said, “and say I work harder than you.”

So Jackson picked up the phone again. This time, he dialed his Great Oak head coach, Robbie Robinson, and gave him an idea. Their school was shut down, too, so why doesn’t he stop by, grab some lifting equipment and turn his family’s garage into a gym?

Robinson agreed, so Jackson drove to Great Oak, threw on a mask and walked into the school weight room and came back with enough equipment to make his garage look like Planet Fitness.

He adopted a routine to make Arnold Schwarzenegger blush. He would wake up at 5 a.m., run a mile, return for a workout, then eat — “I would just be really, really strict on my eating,” Jackson said. He would spend time with his family, then toward the end of the day, he’d return to the garage for a core workout. Then, after another run on the treadmill, he’d hit the hay.

“I did that for three months,” Jackson said.

Even when months passed and he returned to Pullman, Jackson kept up the same routines, making himself look like a man possessed. Back then, Washington State’s strength and conditioning coach was Scott Salwasser, who might have thought Jackson really was. Jackson would meet up with Salwasser at 3:30 a.m., sometimes right on the dot, ready to hit the gym for a lift.

Make no mistake, though: Jackson put in so much of this work before he saw any meaningful playing time. So his physical gains may have helped him become a star on the field, but really, they helped him feel at ease talking about his embarrassing moments away from it.

“It kinda came with me transforming my body in a sense,” Jackson said. “When I look in the mirror, it’s like I’m in love with the person that I see. It’s not just like how I look, but it’s how I feel on the inside, what I put my energy towards. I don’t really waver off my course.”

In that way, it should come as no surprise that Jackson has built a career accordingly. Last fall, he started all 13 games for WSU, totaling 41 tackles, including 12 for loss and six sacks. As the Cougs earned their seventh straight bowl bid, Jackson earned All-Pac-12 second team honors, and by the end of the season, he became a semifinalist for the NFF William V. Campbell Trophy, which goes to the best football scholar-athlete in the country.

Across the first two games of his swan song season, Jackson has only done more of the same. In the Cougs’ win over Wisconsin last weekend, Stone recorded two strip-sacks and Jackson recovered each fumble, including one for a touchdown that will live on WSU highlight videos for decades. In short, Jackson has established himself as a program cornerstone, the kind of player who coaches rave about years after they leave.

After last season, Jackson could have. He had his degree. He had completed four years of college ball. He was high on NFL Draft boards. Just not high enough. He wanted to boost his draft stock. He also wanted to finish his master’s degree.

He could have gone elsewhere to do that. He could have hit the transfer portal and landed at a bigger school, maybe even one that survived the Pac-12’s dismantling. Instead, he chose to return to Pullman, the small town that feels so much like his hometown.

“All the people I’ve met here, all the connections, it’s so different from anywhere else I’ve ever been,” Jackson said. “At the end of the day, I wouldn’t see myself going anywhere else or being at a different school than Washington State. I think it really defines who I am, and it makes sense for what I believe in and what my priorities are.”

***

Jackson leaned back in the office chair, the very same one he sat in to chat with reporters after delivering the game of his life in WSU’s upset of Wisconsin, and he had to smile.

“Gosh,” he said. “I’ve been here for a long time.”

In large part, that’s why Jackson gets the opportunity to consider the question he was thinking about: What kind of legacy does he want to leave at Washington State?

Two things came to mind for Jackson: One, he wants to crack the list of program’s all-time sack leaders. “I’m like five away,” Jackson said, “so gotta get jump-started on that here pretty soon.”

That’s the irony about Jackson, though. Even if he torches every offensive line he sees the rest of this season, piling up sacks and ascending up the leaderboard like a man possessed, if that’s all he’s remembered for, he wouldn’t be happy with his career.

He might even prefer to be remembered for wearing fake glasses.

“I want people to remember me as a great character for Washington State,” Jackson said. “More so than on the field, I want to be remembered as an amazing individual in the community, somebody that any Coug fan that saw me out and like was willing to say hi, they felt like I gave them everything I had to be engaged in that conversation.

“I don’t know. When I leave here, I don’t want people just to be like, oh, number 80 was a great player. It’s like, Brennan was awesome. He was a true Coug.”