New generation leads growth of Spokane Tribe’s Labor Day Powwow

Dancers perform during the grand entry at the Spokane Tribe’s Labor Day Powwow in Wellpinit, Wash., on Friday. (Orion Donovan Smith/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

WELLPINIT, Wash. – As hundreds of dancers from across North America poured into the dance hall for Friday’s grand entry at the Spokane Tribe’s Labor Day Powwow, circling the floor to the rhythm of drummers who had traveled 1,500 miles to be there, organizers celebrated the event’s long history while embracing changes they hope will ensure a bright future.

One hundred nine years after the first Labor Day celebration on the Spokane Reservation and following years when wildfires and a pandemic forced the tribe to scale back and cancel the gathering, the powwow committee announced more than 350 registered dancers, a one-third increase from a year earlier. Longtime members of the committee attributed that growth to a new generation of leaders who have built connections with other Indigenous people through years of traveling to other powwows across the continent.

“I’m extremely proud that we have a younger generation getting involved,” said Margo Hill, an associate professor at Eastern Washington University and powwow organizer in years past. “When we did grand entry, I was just so emotional. It was so powerful.”

Derek Abrahamson, who chaired the powwow committee in his second year as an organizer, said he was driven to get involved by memories of bigger powwows in his childhood.

“When I joined the committee, I just wanted it to be big again, like I remember it being,” he said, adding that everyone – Native or not – is welcome at the celebration. “Our powwow is our way of giving back to the circle and letting everyone come and see our land and witness our culture.”

Warren Seyler, a former member of the Spokane Tribal Council and student of the tribe’s history, said that hasn’t always been the case. The first Labor Day gatherings in Wellpinit, he said, were organized by the federal government as part of an effort to break reservations into individual plots of land and force Native people to become farmers and ranchers.

Starting around the the 1930s and ’40s, Seyler said, the Spokane people reintroduced their traditional dancing to the annual gathering, which they called the war dance. They adopted the term “powwow” in the 1970s, as members of the Spokane and other tribes traveled across the land that is now the United States and Canada and shared their cultures with each other.

“What people don’t realize is that up until probably the mid-20th century, they still didn’t want us to be Indian,” Seyler said. “Racism was alive and well, and so we understood that in order to hold onto our culture, we had to come out into the open in that celebration of who we are.”

This year’s powwow, which continues through Monday, brought people from as far away as Florida, said Dave Madera, a powwow committee member and emcee. The increased registration is partly due to record cash prizes for the winners of each dance contest, he said, some of which are sponsored by families in honor of their loved ones.

“As Natives, we like to give away,” Madera said. “We have more honor in giving away than receiving.”

After the government forced Native Americans onto reservations, it changed course in what is known as the termination era in the 1950s and ’60s, enacting policies that scattered tribal members to cities across the country. The Labor Day Powwow in Wellpinit, Seyler said, helped the Spokane people maintain the tradition of gathering they used to do to harvest salmon, berries and camas.

“There’s no more salmon in the river to gather. We can’t go to the root fields anymore to gather. We can’t go to the berries in the mountains to gather. We can’t go anywhere else to do what we used to do at these large gatherings. The powwow has taken that place,” he said.

“It’s really helping maintain, openly and publicly, our culture and our traditions – and sharing that with multiple generations.”

At 20, Sophia TurningRobe is the youngest member of the powwow committee. The Whitworth University student said she had never missed a Labor Day Powwow in Wellpinit, which she called “a place that I hold really near and dear to my heart.” While she travels to participate in dance contests at powwows across North America and has danced at Wellpinit in past years, she decided this year to focus on helping to organize the gathering.

“We are really wanting to make this celebration really big and we just wanted all hands on deck for that, so it was just on my heart to do it,” she said. “Being able to come together and celebrate brings a lot of healing. After COVID, seeing everyone, seeing new faces, seeing old friends, it’s really heartwarming.”

Ronald “Buzz” Gutierrez, also known as Su-ull-lu-lu-stu, is TurningRobe’s grandfather and a longtime member of the powwow committee.

“It’s inevitable, change,” he said, sitting at his campsite between travel trailers. “See this trailer? We used to live in teepees.”

While he lamented some of the changes the annual celebration has undergone over his 76 years, Gutierrez said he was heartened to see younger generations carrying on the most important traditions.

“What keeps my heart floating,” he said, is seeing his granddaughter’s commitment to the celebration. “She gave up dancing this powwow to help with it. Man, I was just so proud. She knows what this is all about.”

As the dancing continued late into the night, Gutierrez sat across the powwow grounds where people played stick game, a traditional game between two teams in which a “hider” conceals a bone piece in each hand – one white and the other marked with a dark band – while the other team tries to guess which hand holds the white bone. Each team drums and sings as they try to distract the other, while spectators bet on who will win.

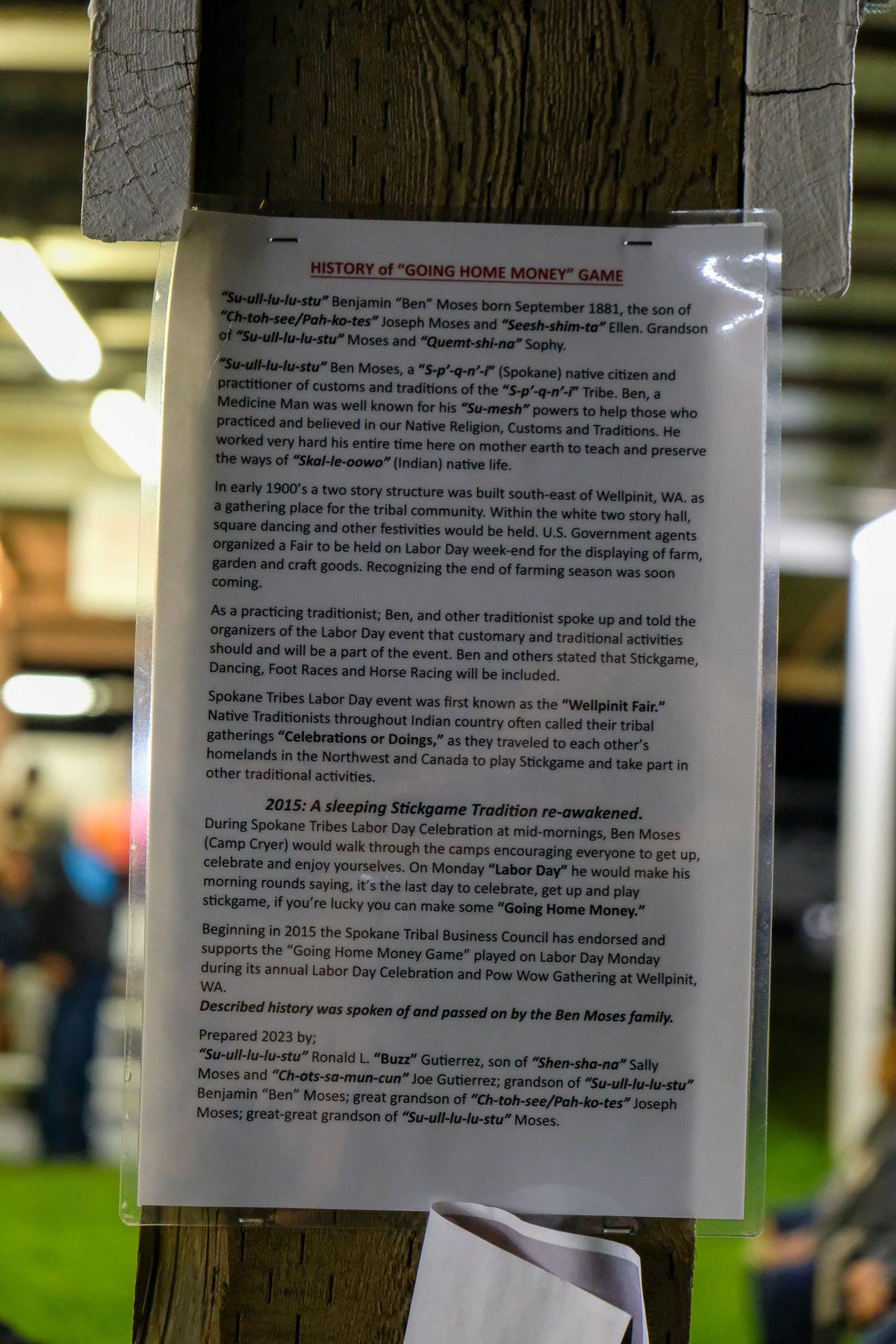

Gutierrez said his grandfather and namesake, Su-ull-lu-lu-stu, also known as Ben Moses, encouraged people to play stick game in the early years of the Labor Day celebration in Wellpinit. The Spokane Tribal Council endorsed the game and officially brought it back to the powwow in 2015.

It’s a seemingly simple game, Gutierrez said, but one that involves much more than simply guessing. He explained that each team, many of them from families he has known for decades, has its own style, songs, tricks, sense of humor and more that a strong player will remember.

Like so much that goes on at the powwow, he said, it’s really about coming together and knowing each other deeply.