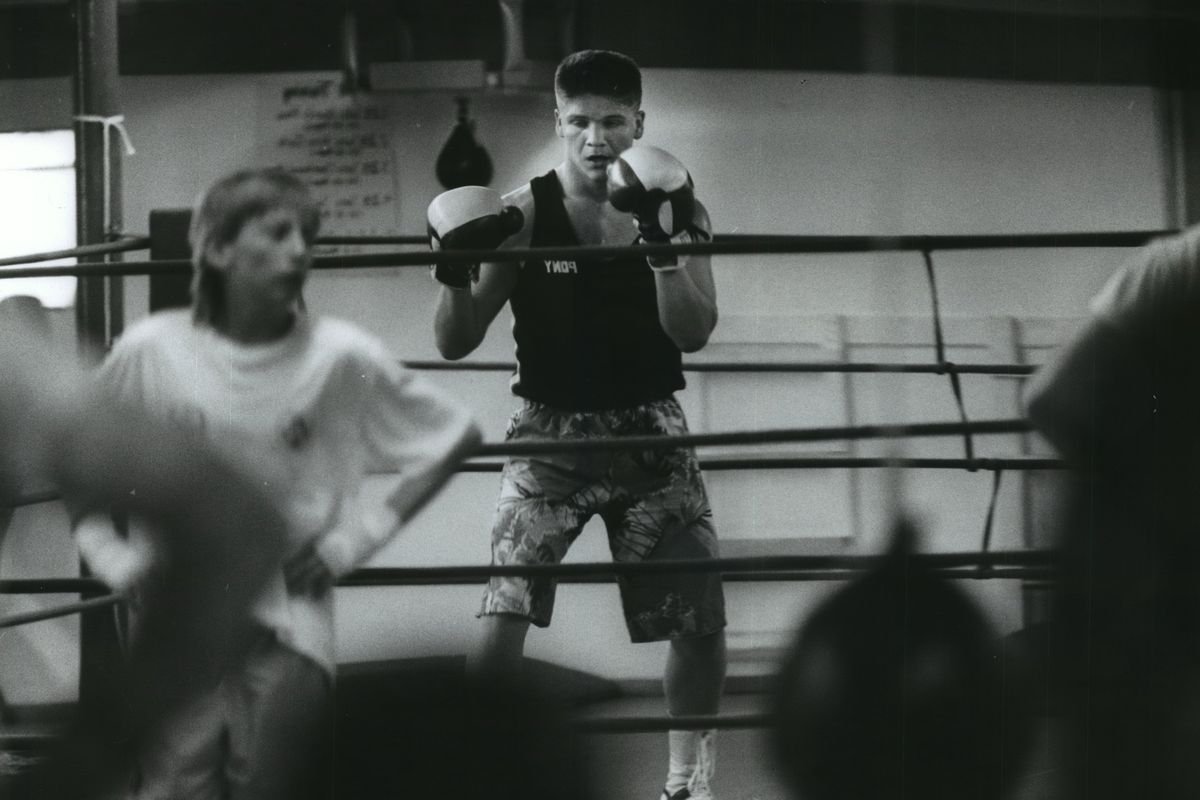

‘Bringing new life to me:’ Retired from his decorated military career, Spokane native Frank Vassar focuses on life as a boxing trainer, just like his dad

Frank Vassar recently visited Spokane, watching his nephew play football for West Valley High and checking out local boxing gyms to gauge the sport’s popularity. (DAN PELLE/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)

Frank Vassar is again following in the footsteps of one of his heroes.

First, as a boxer, he emulated his older brother Dan Jr., a highly successful amateur fighter who helped push Frank on his journey to becoming a 1990 National Golden Gloves winner, a four-time national amateur champion and a solid professional light heavyweight with only one defeat.

Now, the Spokane native is leaning again on the extensive ring knowledge passed down by his father and trainer – Dan Sr., who died in 2010 from cancer at age 64 – in his quest to mold a raw, former NFL player into a heavyweight champion.

“My dad was brilliant,” said Vassar, a 1987 graduate of West Valley High School now living in Choctaw, Oklahoma, just east of Oklahoma City. “I would say probably 80% of (what I teach) came from him and I put a twist on it.”

In addition to training his sons and helping to create a local Northwest boxing scene that thrived for decades, Dan Sr. was a legend in the world of amateur boxing, coaching Olympic hopefuls and national teams. But while his father preferred coaching amateurs – he even dissuaded Frank from turning pro for many years – Vassar prefers coaching professional fighters because of their singular focus.

“As a pro, the guys are out there and in many cases, it’s to get that title,” said Vassar, now 54.

As a trainer, Frank has had that same focus. It’s why he stopped training groups of students earlier this year and devoted himself to just one fighter, former Miami Dolphins defensive tackle Calvin Barnett, who stands 6-foot-3 and weighs a rock-solid 256 pounds.

Vassar said Barnett has shown big potential despite just five fights – all wins – under his belt, including a 3-0 professional record.

“I really like the fact that he listens to everything I say and he tries to do it,” Vassar said.

It’s how Frank thrived under his dad’s tutelage more than 40 years ago, first climbing into the ring at the Spokane Eagles at age 7 .

While training alongside Dan Jr., who also was a four-time national champion and finished with 159 amateur fights, Frank eventually eclipsed his brother’s boxing exploits, thanks to vicious left hooks and overhand rights that left opponents in pain – and in awe.

“I had big shoes to fill trying to keep up with my brother Danny,” Vassar said.

As an amateur, Vassar knocked out 117 fighters while cruising to a 249-39 record, falling just short of making two Olympic teams.

Vassar visited Spokane recently and watched his nephew’s football game – during which his alma mater beat rival East Valley 41-21. He also visited several boxing gyms around the city, and said he was sad to see the boxing community has diminished since he last boxed in the Lilac City 25 years ago.

It’s the same story everywhere, he said.

“We (used to have) 600 people entering a tournament here,” Vassar said. “Today you’d be lucky to have 100.”

A lot of that success was due to his father, he said. Dan Sr. would hold multiple amateur cards each year and would also take his Spokane-area boxing teams to events around the country.

“(Dan Vassar) was pretty much the Obi-Wan Kenobi of boxing,” Spokane Boxing owner and trainer Rick Welliver said.

In a 2010 story in The Spokesman-Review, former Central Valley High School girls basketball standout Andrea Kallas talked about Dan Sr.’s influence in her fighting career.

“In all my years involved with elite-level athletics, I have never had someone inspire me as much as Dan,” said Kallas, who earned Golden Gloves titles . “I will always remember him in my corner, calm as can be, looking me in the eye saying, ‘You got this. This is your fight.’ I would look back and say, ‘I got this. This is my fight.’

“There was never anybody in my life that I wanted to work harder for and win harder for. Dan Vassar taught me to not only be a champion in the ring, but also in life.”

His influence was an equally strong force for Frank, who held off on his professional ambitions for many years and many reasons, among them was that his father preferred him to remain an amateur to protect him, he said.

“Family was the most important thing to my dad,” Frank said. “He passed that on to me.”

Frank delayed his pro decision until he graduated from Eastern Washington University in 1993 with a degree in government, and fulfilling his commitment to the U.S. Olympic Committee, which helped pay for his education as long as he continued fighting as an amateur.

Finally in 1996, he made the move.

“After college (is) when I decided I was going to go pro no matter what, with my dad’s support or not, I wanna go pro,” Vassar said.

With his dad in his corner – literally and figuratively – he won his pro debut and reeled off 12 consecutive victories, most in front of boisterous, family-friendly crowds at the Coeur d’Alene Casino.

“It’s not every day that you get a chance to spar with a national-level fighter,” said Welliver, who fought on many of the same professional cards as Frank at the Worley casino in the mid- to late 1990s. “(He) taught me a lot, showed me a lot and beat me up a lot. It improved me and I was a better fighter because I was in the ring with him.”

On April 1, 1998, in Worley, he lost to Ed Dalton while defending his IBA Continental Light Heavyweight title. Vassar went on to win three more fights, the last as a heavyweight in 2000, but his heart wasn’t in it anymore.

Vassar – who spent his college years in the Army National Guard before transferring to the Army reserves in 1997 – turned his full attention to the military, entering the Air Force full time in December 2000 as a first lieutenant.

And much like in his fighting career, he soared.

The first deployment came in 2004 to Baghdad, where just weeks into his tour, he was part of his first firefight. That year, he was a recipient of the Air Force Combat Action Medal.

“During my deployments, I learned to think quickly and act accordingly,” Vassar said in a text message. “After being caught in a complex attack by enemy forces, I realized how important boxing was for my survival.

“I have been in a ring most of my life, and it allowed me to process everything like it was in slow motion. Everyone in the convoy got out safely. There’s not a day goes by that I am not thankful to God for allowing me to live another day.

“Later that day, I called my dad and told him about the attack. I explained how I was completely relaxed during the attack and concentrating on my breathing.”

His second deployment sent him to Kandahar, Afghanistan, and his third sent him back to Baghdad, where he served as an anti-terrorism officer of the Green/International Zone.

He earned the Army’s Combat Action Badge in 2010.

Along the way, he never strayed too far from the ring. In 2004, he was the officer in charge of the Air Force boxing team that earned the most medals in competition up to that point. In 2009, he trained an army sergeant to a second-place finish in a boxing event held in Balad, Iraq.

By 2013, he’d earned 100% disability for his military service after sustaining injuries in 2004 and 2009 in separate operations in Iraq. He retired with a rank of major.

Still, the itch to train boxers remained.

Soon after, he began working with two fighters in Oklahoma, an amateur and a pro. Two years later, the number of fighters with whom he worked was up to 40.

It wasn’t until 2022 that he limited his training to professionals, including Barnett. His work with local boxers in Oklahoma – as well as his rich history as a fighter in Washington state – caught the eye of former boxer Ronnie Warrior, a Tulsa, Oklahoma, native who fought 20 times and watched Vassar many times in Worley. Warrior was starting an Oklahoma Boxing Hall of Fame and made Vassar part of the inaugural class in June.

“That came as a big surprise,” Vassar said. “I didn’t even know this was being done behind my back.”

That’s not the only effort to gain recognition for Vassar. American Professional Boxing Association President Richard Jackson, who watched Vassar from his first days in the ring, recently nominated Vassar for the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

“It’s a wonderful situation, because now (Vassar’s) not only coaching, he’s mentoring,” Jackson said.

Just like his dad.

“Calvin is bringing new life to me,” Vassar said by text message of his heavyweight prospect. “We have a strong trust for one another.”

Vassar said that’s partially why he’s only training Barnett. Both are aiming for him to be the next heavyweight champion.

“That’s why I’m focused with the man I have,” he said. “(Barnett has) all of the tools.”

Sports editor Ralph Walter contributed to this story.