Book review: In ‘How to Make A Killing,’ Tom Mueller turns a sharp eye to a broken health care system

Author Tom Mueller will be in Spokane on Monday to talk about his new book, “How to Make a Killing,” with the Northwest Passages Book Club. (Dave Yoder)

One of the scariest stories you’ll read this October, right before Halloween, is the true story about the business of for-profit health care in America.

There are no real mad scientists in Tom Mueller’s “How to Make a Killing,” but there are overbearing executives, greedy doctors and complacent politicians who fuel the Frankenstein-like corporate monster that contributes to “Blood, Death and Dollars in American Medicine.”

Mueller, an investigative journalist who has ties to Spokane, details the fraud, corruption and profit-seeking in the kidney dialysis industry. That segment serves as a precautionary narrative and symptom of what’s wrong with health care in the United States.

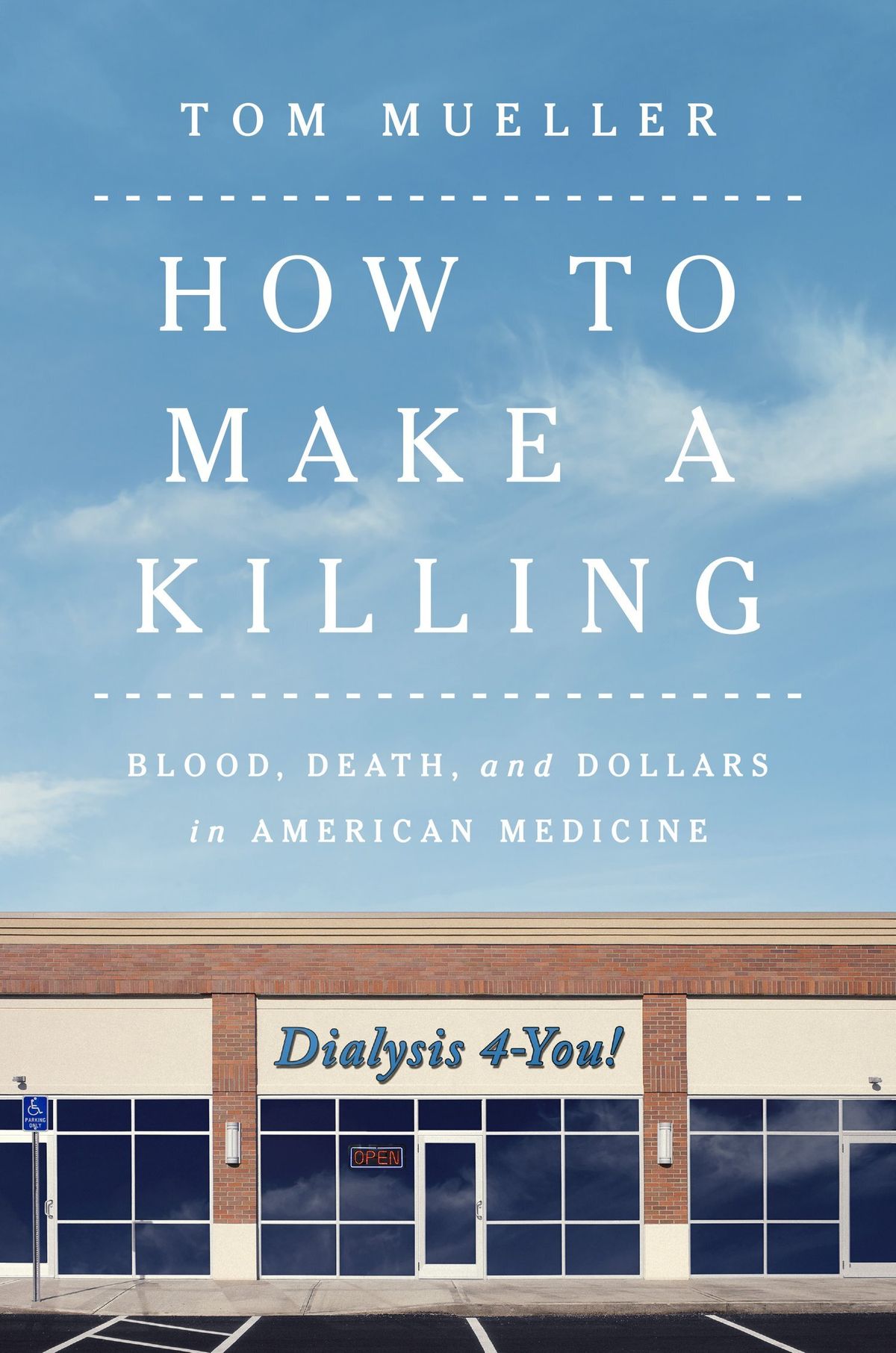

It’s an important book holding to account those who abuse the system, from the local strip mall dialysis center to the halls of the U.S. Capitol.

What at first might seem to be a heavy book actually is a breezy read of 204 pages, made compelling by Mueller’s detailed research (with 59 pages of end notes) and the real-life stories of patients, advocates and people who have fought to bring care back to the business of health.

Mueller also provides vivid history of science and technology and its efforts to overcome kidney disease, one of the deadliest diagnoses for humans until the mid-20th century. It’s fascinating to learn how the first dialysis machine emerged in the battle-worn corners of Europe using a bathtub, sausage skins and a sewing machine motor – and it worked.

The author takes us through the development of cannulas and shunts, using Teflon to prevent clotting, at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, innovations inspired by a patient from Spokane.

Those steps would make dialysis available to all and provide the promise of a true medical miracle by the 1960s. Then in the 1970s, Congress would slash through the cost barrier with Medicare and Medicaid, making dialysis available to anyone who needed it in America’s first foray into providing health care for all.

If only medicine had stayed along that high-minded path.

It was only a matter of time until big business realized there was money to be made and ways to make the care cheaper and more profitable.

Mueller takes us through the rebirth of a 19th century economic theory favoring free markets and government deregulation. Forgotten after the Great Depression, President Ronald Reagan and economics advisor Milton Friedman brought back what would become known as Reaganomics, trickle-down economics or even voodoo economics.

It was really a philosophy called neo-liberalism that conservatives and right-wing politics embraced.

Still, government grew instead of being contained and corporations, especially in the business of medicine, fed at the public trough. Nowhere was this as evident as in the growing business of private dialysis centers. These businesses eschewed slower home treatments embraced by Europe, Australia and other industrialized countries in favor of quicker, more aggressive – and more lethal – methods that were more cost effective and higher profits.

We hear Kent Thiry, chief executive of DaVita, one of two firms (along with Fresenius) that control the dialysis market in the U.S., bragging in a speech at UCLA how he ran a business on which people’s lives depended as if it were a Taco Bell. A former employee of Thiry’s, meanwhile, compared the corporate culture inside DaVita to growing up in Communist Romania.

“Do no harm” gradually gave way to “show me the money.” The ones suffering the most were the patients for whom the treatments were invented.

“Neoliberalism has created a system in which the government collects money with taxes, but instead of using that money to provide health care directly to patients, the government hands the money over to private corporations, which have insinuated themselves between the population and the Treasury. The corporations become toll booths that collect economic ‘rents – unnecessary profits that provide no additional services – from the practice of medicine,’ ” Mueller writes.

Even economists who believed in the free-market system changed their minds upon being exposed to the dialysis business.

Economist Ryan McDevitt decided to study the business, confident he would find an example of business efficiency and economies of scale. Instead, he and colleagues found big chains preferring profits over patients and quantity over quality. “Trying to get more turnover, like you would in a fast food restaurant, leads to a direct sacrifice in patient care and to bad outcomes,” he says.

There are heroes, such as Arlene Mullin, an advocate for dialysis patients who lived in a trailer home in Georgia and developed a nationwide network to help patients who suffered in an unfair system.

We also meet John Agar, Australian nephrologist who has been building a working model that prioritizes patients. His patients administer their own treatments at home and instead of slowly degrading, as in the U.S., they go hiking and longboard surfing.

“For many years, I’ve been telling my American colleagues, ‘You have to stop killing your patients.’ ” Agar says.

And there are others who buck their bosses and maintain fight for both health and care.

“Despite the negative environment that the company’s culture can create for patients, in any given center, one strong, principled nephrologist, nurse or tech can make a huge difference in a patient’s life,” Mueller writes.

But money, power, and politics still rule the day, continuing to put America at the bottom of the world in health care outcomes. That’s especially true with kidney disease, where dialysis and transplants were among the first treatments to offer real hope.

Mueller provides a cautionary tale that exposes an underbelly of greed in the medical industry, one where people willingly sell off ethics and care to the highest bidder.

The question remains, is it too late for the medical world in America to heal itself?

Ron Sylvester has been a journalist for more than 40 years with publications including the Orange County Register, Las Vegas Sun, Wichita Eagle and USA Today. He lives in rural Kansas.