Spokane County spending $625k on energy efficiency audit

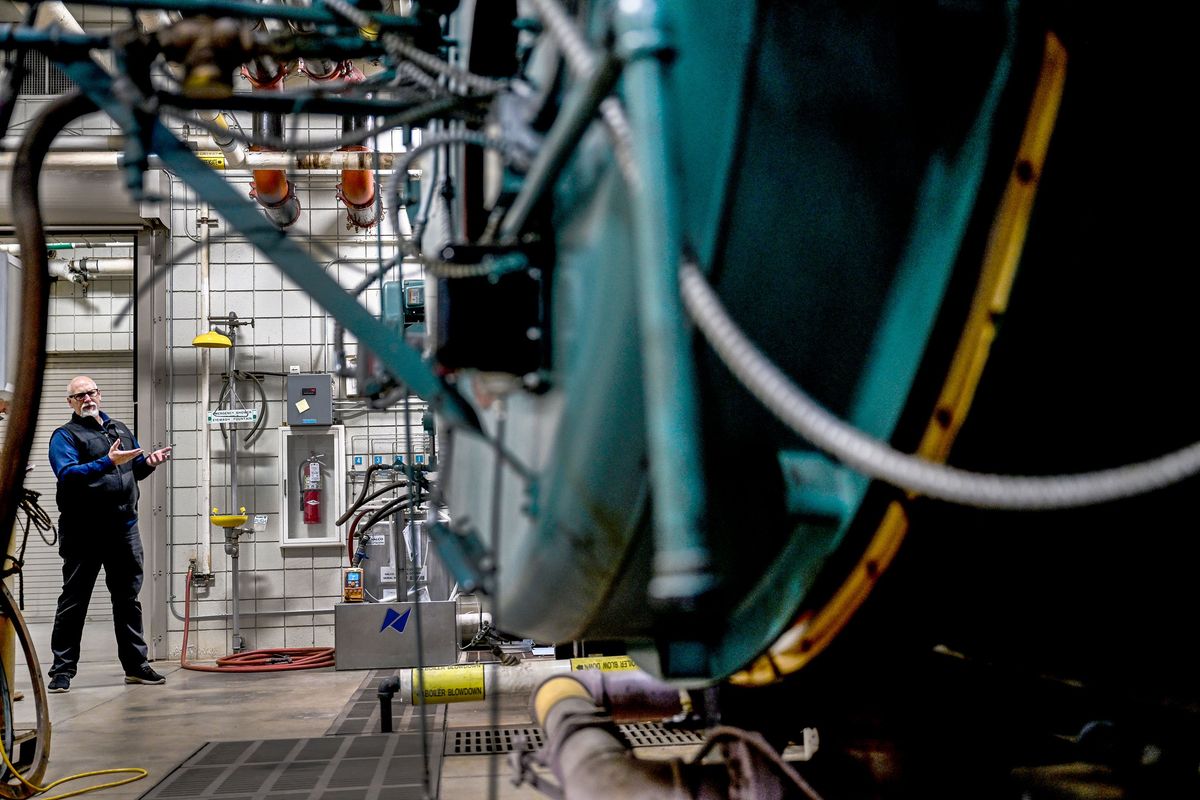

Gil Haubert, Spokane County’s facilities director, talks about the boilers that heat buildings on the county campus on Friday. (Kathy Plonka/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Four SUV-sized boilers sit in a big, plain building behind the Spokane County Courthouse.

The powder blue behemoths have sat there for decades, and they do an important job. They burn natural gas to generate heat, which converts water to steam. That steam travels via pipe through a series of underground passageways, before heating the courthouse, jail and other buildings on the Spokane County campus.

The boilers rumbling in Spokane County’s heating plant have done their job well, but their days are numbered. Not only are they falling apart, they’re woefully inefficient and the exact type of energy infrastructure the Washington Legislature was trying to discourage when it passed the Clean Buildings Act in 2019.

The law, written in hopes of reducing energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, established a set of efficiency standards for buildings larger than 50,000 square feet. The new rules go into effect incrementally over the next few years.

Spokane County will be required to increase the energy efficiency of several large buildings, including the courthouse and jail. With those upcoming deadlines in mind, the Spokane County Commission recently approved a $625,000 contract with the consultant Johnson Controls to audit the county’s buildings and develop an energy savings plan.

While the state Legislature is forcing the county to make its buildings more energy efficient, Spokane County Facilities Director Gil Haubert sees the situation as an opportunity.

The boilers and other components of the county’s heating and cooling infrastructure system need to be upgraded, Haubert said. Even if the state wasn’t requiring energy efficiency improvements, the county would have to make expensive investments in new systems soon.

Spokane County Commissioner Josh Kerns, a Republican who rarely hesitates to criticize progressive laws written in Olympia, acknowledged that the Clean Buildings Act isn’t imposing an enormous burden on the county.

“Though I don’t like when the state forces us to do things, this is something that we would have had to do eventually anyway,” Kerns said.

While Johnson Controls will give Spokane County a list of energy saving possibilities, Haubert has a good idea of what’s likely to happen.

The county will probably abandon its centralized heating plant and install separate boilers in each building.

“We see the efficiencies in going back to decentralization,” Haubert said.

Spokane County built its centralized heating plant, with the four gigantic boilers, in the late 1980s.

The decision to build the facility wasn’t one the county commission took lightly, and discussions about the proposal were front page news in March 1986.

Then, as with now, county officials were reacting to forces outside their control.

Until the late 1980s, Spokane County bought steam from Washington Water Power, the utility company now known as Avista. The steam came from the Steam Plant, an iconic two-towered building that remains a fixture in the downtown Spokane skyline.

By the mid-1980s, Washington Water Power was working toward phasing out the Steam Plant. Spokane County and other downtown property owners were going to have to find steam elsewhere.

The county opted to build a miniature steam plant of its own, a roughly $7 million investment equivalent to about $20 million in 2023 dollars.

At the time, Haubert said, heating the county campus with gas-fired boilers from one central location was the most efficient option. That’s no longer the case.

Spokane County’s boilers are only about 60% efficient, Haubert said. The boilers’ insulated linings – known as refractories – are failing, which means heat that should be captured is leaking out and being wasted.

New boiler systems are about 90% efficient. The county could buy boilers that still run on natural gas, but they’d be far smaller. Instead of clustering them in one place, Haubert’s team could put one in every building.

Buying new boilers won’t be cheap. Haubert estimates that a full energy efficiency overhaul would cost $10-15 million.

But by increasing efficiency, the county would save a small fortune on gas and electricity. Haubert said the annual savings would likely fall in the $500,000 range.

Spokane County Commissioner Chris Jordan said he hopes energy infrastructure upgrades could lead to long-term savings.

“With this audit, upgrades could be a win-win,” he said, “for taxpayers, the work force and our energy efficiency.”