Even after the pandemic, broadband is critical for rural education. $1 billion won’t be enough to reach everyone in Washington.

Brandi Jo Desautel works to print out an assignment due at Spokane Community College branch in Inchelium, Wash., on Monday. The lack of reliable internet service is one of challenges of living in rural Inchelium. She has Starlink, but the connection is sometimes inconsistent. (Kathy Plonka/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Last year, Brandi Jo Desautel installed a SpaceX-powered Starlink dish in front of her trailer outside Inchelium, Washington, on the Colville Reservation. At $700 for the equipment and $120 a month for service, it wasn’t cheap. But for her, it was the only option.

Some folks in town have basic internet through their cable provider, but the network doesn’t reach the 32-year-old’s address. A paraprofessional for Inchelium High School, Desautel is out of range of wireless towers, and cellphone coverage is spotty.

Satellite internet allows her to take online classes at night from Spokane Community College, where she is working on a special education degree. It also helps her twin daughters, grade 6, do their schoolwork from home.

“Between my school and theirs, we don’t have a choice,” Desautel said.

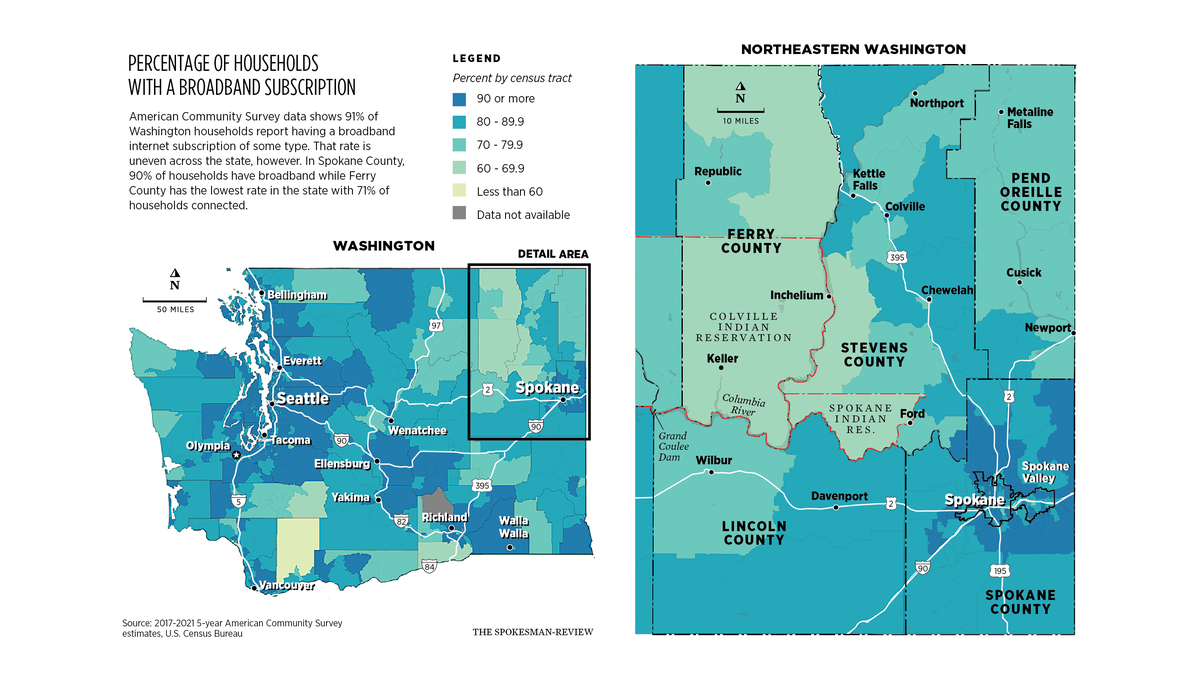

Even though classes are back in person after the COVID-19 pandemic, access to reliable home internet remains critical both for a well-rounded education and for participation in modern life. Yet some 236,000 Washington households still don’t have broadband-level speeds or internet access at all – many of them in rural areas like where the Desautels live where it is not as profitable for internet providers, according to Federal Communications Commission data.

Over the past few years, Congress has invested hundreds of millions of dollars to expand broadband infrastructure in Washington. Another $1.2 billion will begin rolling out as soon as next year. All of this federal funding will do a lot to bridge the digital divide, but it probably won’t be enough to meet the state’s ambitious goal of universal high-speed internet for every address by 2028.

Accessible by ferry across the Columbia River on the east side of the Colville Reservation, Desautel’s hometown of Inchelium has some of the worst internet coverage in Eastern Washington.

That should change soon, as the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation are expanding their network with the help of a $48.4 million federal grant to bring fiber and wireless internet to 2,867 unserved Native American households and several hundred businesses and institutions in Inchelium and nearby Keller. The grant is part of the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program, a $3 billion fund from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

The Spokane Tribe was awarded $16 million for a similar project.

“In the modern world, internet access is critical,” Colville Business Council Chairman Jarred-Michael Erickson said. “It is especially vital for our youth and their education.”

Although she is not an enrolled member, Desautel is a direct descendant of the Colville Tribes. She lives near extended family several miles down a dirt road in an area northwest of town called Seylor Valley, or simply “The Valley” to locals.

Her satellite service cuts out sometimes. Other times, she loses internet because of power outages.

“The hardest part is convincing teachers to let me turn in late work,” Desautel said.

Starlink is becoming more popular among Desautel’s neighbors, but many cannot afford it. It could be a few more years before residents like Desautel get connected.

Growing up in a digital ‘desert’

Nearly every public school building in Washington has broadband ethernet through the state’s K20 Education Network overseen by the Office of Financial Management. The network includes K-12 school districts, public libraries and colleges.

The challenge is to bring that same level of access to students’ homes.

During the pandemic, many school districts used COVID relief money to provide hotspots for students, but much of that funding has run out.

School districts with less internet access tend to adjust homework requirements accordingly.

John Farley, superintendent of Republic School District in Ferry County, said his district accommodates students by not demanding work that would require internet at home.

“We want to make sure they are getting everything they need at school,” he said.

Farley noted the growing importance of technology in education and teaching online literacy and safety. The internet becomes more important as students apply for college or jobs, he said.

Rob Clark, superintendent of Washtucna School District in Adams County, said most of his students live in town, where they have internet access. Washtucna was awarded a Washington state Public Works Board grant in 2021 to build fiber to the homes in town.

“I can’t say it is a real big issue here,” Clark said. “It is a problem, but it is a minor problem.”

Washtucna is a tiny district with about 70 students where everyone can take home a Chromebook. The district is capable of going fully remote again in case of bad weather or another outbreak, Clark said.

Internet levels vary from district to district. Most incorporated towns in Eastern Washington have basic broadband options, and ongoing grant projects will make those options better. The larger challenge will be to reach those in unincorporated areas, especially those who don’t live near major highways.

Margaret Kidwell, supervisor of Spokane Community College’s center in Republic, said some students don’t have internet at all, and a few don’t even have electricity.

With mountainous terrain, many places in Ferry County don’t have cell service, so hotspots don’t work. Kidwell said she knows one person who uses a solar panel just to power their hotspot.

“We live a lot differently up here,” Kidwell said.

Students without internet will do their homework at the college office or the local library. Running start students – high schoolers who take classes for both high school and college credit – do their homework at the high school.

Teri Ford-Dwyer, a business instructor at Spokane Community College in Newport, Washington, teaches students across the state’s three northeastern counties.

She teaches “flex” classes, which are more flexible than hybrid classes by giving students a choice to attend each class in person, live on Zoom or to watch the recorded lectures later. This option is helpful for working parents, like Desautel, and those who live far away with spotty internet.

Bandwidth is a constant struggle for her live video classes. Many students turn off her video feed and just listen. Most students keep their cameras off. If they can’t even use audio, they will type in the chat. Students will often lose connection in the middle of class, then rejoin.

Students miss out when they don’t have fast enough internet to fully participate, Ford-Dwyer said.

They don’t get the same level of interaction with their fellow students during discussions. Peer relationships are an important part of the college experience because students learn from each other.

With the help of the internet and branch centers, SCC is able to reach rural students in a way it couldn’t before. Universal broadband would make it even easier.

“The course offerings are there, but the infrastructure hasn’t caught up,” Ford-Dwyer said.

Michael Gaffney, assistant director of Washington State University Extension, said internet access is not only important for college students, but for adult education and workforce development.

WSU Extension offers a 30-hour remote work certificate. As a prerequisite, some students have had to figure out how to get a high-speed internet connection, Gaffney said.

During the pandemic, WSU introduced 24-hour Wi-Fi at more than 30 extension offices. With the state broadband office, WSU Extension maintains a map of hundreds of free drive-up Wi-Fi locations across Washington.

For some, this remains the only way to access the internet.

Allen Pratt, executive director of the National Rural Education Association, said reliable internet is essential for K-12 students, too.

Although they might get by, growing up without the internet could leave these children behind their urban and suburban counterparts. Faster internet means more capabilities and educational opportunities.

And if a student has to ride a bus for an hour or more and they come home to slow internet, it will take them longer to get their work done.

“This is an equity issue,” Pratt said. “If we don’t have communities with the same access, it’s not equitable. We’ve got to do something as a country to make that equal for all.”

While many school districts lend devices and hot spots, one Whitman County school district has taken an extraordinary step of providing broadband infrastructure directly to its students.

Pullman Public Schools’ technology director, Garren Shannon, spearheaded a $1 million grant from the state broadband office to build four wireless internet radio towers in Pullman, Albion and Tekoa.

The stark divide during the pandemic between students who had quality internet and those who didn’t inspired him to do something about it. The district will distribute 60 specialized Chromebooks in the coming months for students to connect to the closed network.

West Plains companies New J and Peak Industries designed the retractable telescoping towers, which range from 65 to 120 feet tall and can be relocated if needed.

Some questioned why Pullman, home of Washington State University, needs such a program.

“If you drive 2 miles out of town, it is a desert, digitally speaking,” Shannon said.

Albion, just northwest of Pullman, is a part of the school district with cheaper housing and many low-income residents. Town clerk Starr Cathey said students sit outside the library in the winter using the Wi-Fi to do their homework, since the small branch is only open a few hours a week.

Stories like that make Shannon want to expand the pilot program to more districts. That’s why the program also includes Tekoa, a small town with its own school district in the northeast corner of the county with a similar profile to others across the Palouse, whose rolling hills make long-range wireless difficult.

“If we can make it work there, we can make it work anywhere,” Shannon said.

What $1 billion can do

Scott Hutsell, a hands-on Lincoln County commissioner, used a forklift on a recent Monday morning to unload 20,000-foot spools of fiber-optic cable from a delivery truck into a semi-cylindrical warehouse. The spools, along with dozens of pallets of related hardware, are temporarily stored at the fairgrounds in Davenport until contractors pick them up and string the fiber, mostly along telephone poles, across the county.

It’s part of a series of projects from more than $20 million of federal and state grants to connect the county’s eight incorporated communities with fiber. The projects, overseen by the county’s recently created broadband office, also will build redundancy into the network by creating more connections between towns.

Some internet providers are expanding their networks, but the free market falls short in low-density places like Lincoln County.

“No one else was going to come here,” Hutsell said. “They would have been here already if they could make money.”

The model is a little different from other counties, which mostly operate their broadband projects through a port or public utility district. Instead, Lincoln County owns and oversees the project directly. The goal is to run it as a self-sustaining business where internet service providers will be allowed to use the network for a fee, then the county will reinvest the profit to maintain and expand the network.

The Federal Communications Commission defines broadband speed as at least 25 megabits per second for downloading and 3 megabits per second for uploading. This is abbreviated as 25/3 Mbps.

Some say that is too slow.

A household’s bandwidth needs depend on the type of use and the number of people using different devices at the same time. Email and web browsing require minimal bandwidth, video streaming requires a little more, and video conferencing and gaming require a lot.

Washington’s stated goal is for all businesses and residences to have 25/3 Mbps by 2024 and 150/150 Mbps by 2028.

To date, the federal government has invested $705 million for broadband projects in Washington, while the state has invested $68 million. Another $1.23 billion will soon be coming from the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program, which was funded by the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

That will almost certainly fall short of the state’s goal.

The Washington State Broadband Office estimates it will cost at least another $2.02 billion to serve every remaining location with fiber. Even with BEAD’s 25% match requirement, there is still a gap of nearly $500 million.

Fiber is the preferable broadband technology because it is most reliable and has the most bandwidth. But fiber is harder to deploy over large, low-density areas.

Broken down per household, the average cost across the state for a fiber connection is estimated at $8,825. That average is much higher in rural counties, where it can exceed $20,000.

Hutsell said the state’s goal is ambitious, if not overly optimistic, at least for Lincoln County.

“Getting fiber to every home is going to be tough – not that it isn’t a long-term goal,” Hutsell said. “A certain amount of that is going to have to be fixed wireless.”

The broadband office has drafted a Five-Year Action Plan and Digital Equity Plan to help inform how the BEAD money will be allocated. The office is accepting public comments on these plans through Oct. 15 and 31, respectively.

While the countryside takes much of the focus, urban areas aren’t completely connected either. Urban counties with some of the highest rates of subscription, including King and Spokane, also have the highest number of households without broadband, the Five-Year Action Plan points out. These households are often in lower-income or marginalized neighborhoods.

Spokane County last year formed a regional broadband public development authority called Broadlinc to improve access in rural and urban parts of the county.

There are other barriers for people adopting broadband besides infrastructure. It also needs to be affordable, users need devices, and users need to want to and know how to use the internet.

The federal Affordable Connectivity Program subsidizes $30 a month for low-income families and $75 for households on tribal lands. The program’s future is uncertain, as its funding is set to run out sometime next year, unless Congress renews it.

Some 307,000 Washington households are enrolled in the program, according to the Universal Service Administrative Co. ACP Enrollment and Claims Tracker.

Advocates say broadband should be a universal utility, comparing it to New Deal-era investments in the electric grid, telephone lines and the public road system. Some go so far as to call it a human right.

Michael Gaffney said broadband for everyone is a worthy a goal, even if it isn’t 100% achievable.

“As technology advances, we’ve got to recognize broadband is not a luxury, it is a necessity,” Gaffney said. “It’s like water or electricity.”

Reporting conducted for this article was completed with funding from a Center for Rural Strategies and Grist grant program.