Inland Empire Paper Co. seeking millions from feds to maintain ‘working forests’ as development pressure builds

Thousands of acres of conifers cover the Inland Empire Paper Co.'s lands east of Mount Spokane on Nov. 21. The company is hoping to receive money from the federal government in exchange for agreeing never to develop its property. (Colin Tiernan/The Spokesman-Review)

Spokane County’s largest private landowner is seeking millions of dollars from the federal government in exchange for conservation easements that would permanently protect from development thousands of acres of forest next to Mount Spokane.

The Inland Empire Paper Co., which owns roughly 120,000 acres in Eastern Washington and North Idaho, is asking the U.S. Forest Service for multiple conservation easements. Inland Empire is owned by the Cowles Co., which also owns The Spokesman-Review.

Congress created the Forest Legacy Program in 1990. The goal is to conserve “working forest” – typically timberland owned by logging companies. By giving loggers a financial incentive not to sell their land to developers, the federal government hopes to protect wildlife habitat, maintain recreational opportunities and preserve jobs tied to timber or paper production.

In the last 33 years, the Forest Legacy Program has paid for about 450 conservation easements on 3 million acres. The program in 2023 invested $188 million in 34 projects.

Idaho has about 100,000 acres protected by Forest Legacy Program conservation easements. Washington has about 70,000 acres in eight counties protected by more than $50 million worth of easements.

The Forest Service prioritizes timberland near large population centers, where urban sprawl is most likely. Peter Dykstra, a consultant for the nonprofit Trust for Public Land, said only a small fraction of Forest Legacy Program applications receive funding.

Conservation easements aren’t all alike, but the general concept never changes. The U.S. government is paying property owners for a legally binding promise: keep the land forested and undeveloped in perpetuity. The easement remains in effect no matter who owns the land.

The Forest Service has funded several conservation easements in North Idaho.

The Stimson Lumber Co. about five years ago agreed to a $9.5 million conservation easement in Bonner County. Clagstone Meadows, which covers more than 13,000 acres, would have otherwise become the site of two golf courses and 1,200 homes.

Washington loggers have gotten conservation easements through the Forest Legacy Program dozens of times, mostly in the Puget Sound area of the Cascades.

But the federal government has never funded a Forest Legacy Program conservation easement in Eastern Washington.

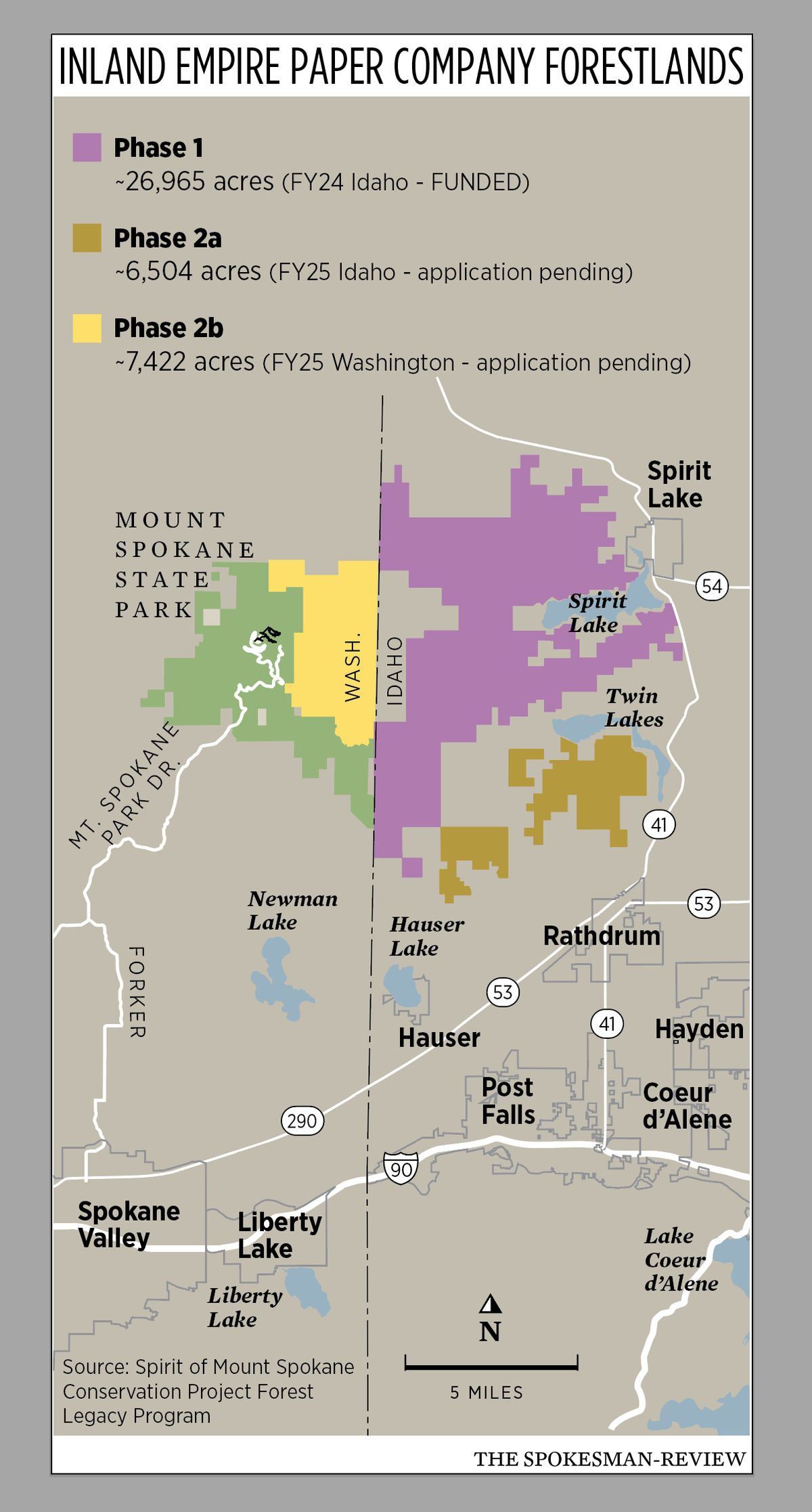

The Inland Empire Paper Co.’s application is a multiphased, multistate proposal. The Trust for Public Land is handling the application process on Inland Empire’s behalf.

In total, the company is hoping to secure conservation easements for more than 40,000 acres of conifer-covered land in Eastern Washington and North Idaho.

Inland Empire Paper Co. President Kevin Rasler said he was unaware of the Forest Legacy Program until a couple of years ago when he heard about the Stimson Lumber Co.’s Clagstone Meadows project. Rasler said Inland Empire wanted to explore the program, regardless of whether it ultimately signed any conservation easements.

The Forest Service has already agreed to pay $13 million for one 27,000-acre chunk of Inland Empire land in North Idaho, although easement negotiations haven’t begun. The property roughly lies between Mount Spokane and Spirit Lake.

On the Washington side, Inland Empire is seeking $5 million for 7,400 acres directly between Mount Spokane State Park and the Idaho border. The Spokane County Commission and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife have both publicly supported the project.

“It seems like these are usually considered win-wins from all political spectrums,” said Jeff McMorris, Spokane County’s community engagement and public policy adviser.

In its letter of support, the Department of Fish and Wildlife said protecting the land from development would be a boon for moose, elk, wolves, deer, westslope cutthroat trout and grouse.

Even if the application is successful, the Forest Service might not offer $5 million. Independent appraisers set the price.

To determine the value of a conservation easement, the Forest Service asks two questions. First, what’s the value of the land if it could be developed? Second, what’s the value if it can’t be developed?

The value of the easement is the difference between those two numbers. In other words, the conservation easement is an attempt to compensate the property owner for the money they’re foregoing by not developing their land.

The federal government only pays 75% of the conservation easement’s value, although sometimes another entity will pay the property owner the remaining 25%.

If Inland Empire’s application succeeds, public access to the 7,400 acres probably won’t change much.

Today, the general public can use the company’s lands for hunting, berry picking, fishing, firewood gathering, Christmas tree cutting and more, but access comes at a price. A permit costs $55 a year.

Numerous agencies have suggested that nonmotorized access to Inland Empire’s lands would become free if the conservation easement happens. Rasler said that’s a possibility, and noted that the company’s nonmotorized use permits only cost a few dollars.

Lacy Robinson, the Forest Legacy Program coordinator for the Idaho Department of Lands, said she thinks conservation easements can help protect the Inland Northwest’s rural character.

“A lot of people like to live in places like North Idaho and really don’t want to see subdivisions popping up everywhere,” she said.

Robinson also said she believes development is a real threat in Inland Empire’s forests.

Rasler agreed. He pointed out that development is exploding on the Rathdrum Prairie, near the forest’s edge. People call Inland Empire on a nearly daily basis hoping to buy property, he said.

“We get bombarded with those requests,” he said.

Rasler said Inland Empire wants to ensure its forests remain covered in trees and not buildings.

“Our primary mission here is to make sure the forest is perpetual,” he said.