Spokane and Washington state face high and rising cases of syphilis from heterosexual activity

Cases of syphilis in Spokane County and statewide are at historic highs and are rising, driven by a surge in cases among those who engage in heterosexual sex.

Until recent years, syphilis was a sexually transmitted disease that predominantly affected men who have sex with men. Gay and bisexual men in Spokane who contracted the disease often got it while traveling to a larger urban area.

Before 2016, few individuals in the Spokane area were infected by the sexually transmitted disease. But syphilis began to spread that year in Spokane’s heterosexual network. As of 2023, approximately 75% of cases in Spokane County are among self-identified heterosexual men and women.

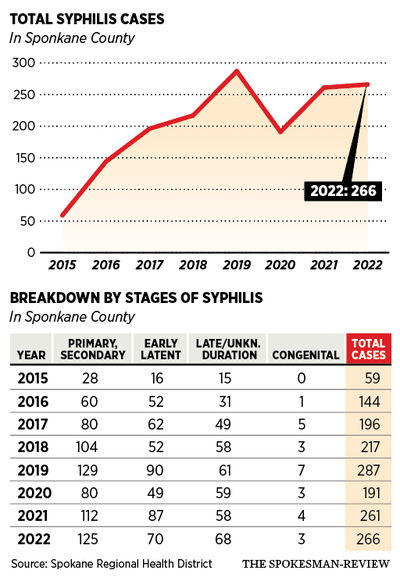

This spread among straight people corresponded to the overall rise in Spokane County cases – rising from 59 cases in 2015 to a peak of 287 cases in 2019.

The number of diagnosed cases fell in 2020, but Spokane Regional Health District STD Prevention Specialist Kirsten Duncan noted that decline likely came from more cases being undiagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Syphilis really requires a physical examination to really understand the diagnosis. So we saw that drop in cases during COVID as we went to telemedicine. And now we’re trying to catch up from the cases that were missed at that time,” she said.

Cases returned to the high prepandemic levels in 2021 and 2022, which saw 261 and 266 cases. Cases are already 40% higher in 2023 compared with the number of cases diagnosed through October 2022.

For much of syphilis’ rise of the past decade, Spokane County has led the state in diagnosed cases. But in recent years, other areas of Washington have had higher rates of syphilis transmission.

While case rates were rising in Spokane, there were 9.2 syphilis cases per 100,000 residents statewide in 2017, according to a 2021 report from the Washington State Department of Health. That number remained relatively constant through 2020 until statewide figures jumped to 19.2 cases per 100,000 in 2021 – compared to just 10.9 per 100,000 a year earlier.

By that point, the rise in cases was driven not only by Spokane County but by the Seattle and Yakima areas. In 2022, Spokane County had 22.7 cases of syphilis per 100,000 residents. King County had 29.2 and Yakima County had the highest rate of transmission of 90.4 cases of syphilis per 100,000 residents, according to the Department of Health.

Duncan said it was unclear if syphilis in Spokane County contributed to increasing syphilis cases in other parts of the state. But the statewide increase was also driven by transmission within the heterosexual community.

Although the number of cases among men who have sex with men rose 38% statewide from 2020 to 2021, the majority of syphilis cases are among straight men and women starting in 2021.

Because much of the nationwide medical guidance for syphilis is targeted toward the gay and bisexual community, there is much less awareness of the sexually transmitted disease among heterosexual individuals.

“There is not really great awareness among (heterosexuals),” Duncan said. “If folks don’t know this is out there and they could potentially come into contact with it, it does make it a lot harder to convince someone that they need to be tested.”

National CDC guidance on syphilis recommend that men who have sex with men get tested for syphilis annually or up to every three months, depending on their risk factors. But with exceptions, straight men and women are not urged to receive regular testing.

In 2021, the Spokane Regional Health District changed its local recommendation, urging all sexually active, nonmonogamous individuals be tested annually.

The health district has four full-time employees and one part-time employee focused on syphilis who do case investigations, screening events and education with health care workers so they are aware of the new testing recommendations.

Syphilis and pregnancy

The heterosexual spread of syphilis also presents another public health concern: a pregnant woman spreading syphilis to a child. These congenital cases of syphilis can be much more severe than the symptoms that occur among infected adults.

Syphilis is spread via the placenta during fetal development. If someone contracts syphilis during their pregnancy or has had an untreated infection in the past five years, there is significant risk to the fetus.

Approximately 20% of congenital cases result in a stillbirth or miscarriage, and there is an additional 9% chance that the infant will die within the first month of their life. Children who do survive are at risk of long-lasting symptoms.

“Syphilis tends to eat holes in things,” Duncan said. “If we don’t get babies treated – and the treatment is a 14-day course of IV antibiotics – then there can be really devastating consequences to the child as they grow. We see things like hearing loss, vision loss and motor-function disability that can all take a few years to show up.

Seven babies were born in Spokane County with syphilis in 2019. Two of those were stillbirths, Duncan said. There have been 26 cases of congenital syphilis since 2015.

Washington has a law requiring providers to conduct a blood test for syphilis at a pregnant person’s first prenatal checkup. But some do not receive prenatal care.

“Our peak of congenital cases was in 2019. But we’ve been a little bit better recently. We’ve been able to treat women while they are pregnant and avert congenital cases,” Duncan said.

What is syphilis and how is it treated?

Syphilis is a bacterial infection that can be spread wherever sexual contact occurs.

Throughout infection, syphilis moves through a series of stages. It will first materialize as a painless lesion where sexual contact occurred that will heal four to six weeks later. It will then move into secondary syphilis, which is a systemic bacterial infection that can affect any part of the body. The most common symptom is a nonitchy rash, which is not infectious.

Syphilis is spread in its secondary phase through red, white or gray mucus patches – most often in the mouth or genitals.

“You can have those symptoms anywhere on your body, even if you only had oral sex. Because at that point the bacteria is moving through your whole body and impacting it anywhere it can take hold,” Duncan said.

Other symptoms during secondary syphilis include hair loss, low-grade fever, chills, malaise, sore throat and fatigue. Symptoms in this phase will come and go for a period of six to eight months.

After secondary syphilis, the disease becomes latent and without symptoms – where it can hang out in the body and do damage that shows up 10 or 30 years later, Duncan said.

Symptoms in this long-term tertiary phase of the disease can include open wounds, neurologic conditions, brain lesions and gait instability.

In the modern day, infected individuals rarely reach the tertiary phase without receiving treatment. Most of these symptoms are associated with “scariness we think about from long ago before we had medication to treat it,” Duncan said.

If they acquired the disease in the past 12 months, syphilis can be treated and cured if an individual receives a one-time shot of long-acting penicillin. If the infection occurred more than a year ago, there is a regimen of three injections over three weeks.

Condoms and other forms of barrier protection can be effective in preventing syphilis, Duncan said, but only if used for oral sex as well as anal and vaginal sex.

The most important way to guard against the disease is regular testing, she added.

“The symptoms can be really hard to notice. They’re very nonspecific. The best way to know if you have syphilis is to get tested,” Duncan said.

Tests for syphilis require a blood draw, so if getting STI testing, make sure to give blood in addition or instead of a urinary test or swab. Testing for syphilis may not pick up a recent infection.

Duncan expects syphilis to continue to rise in Spokane in the short term before a gradual decrease.

“I think we still have cases that are not yet diagnosed from the pandemic. And so as we work with our health care providers to have them do all the screenings, we’ll likely find more cases before we start to see that decrease.

“But if we catch cases sooner, and we treat them before transmission occurs, then I expect to see a decrease over time,” she said.