‘Like an open wound’: Washington task force holds event to highlight missing and slain Indigenous women

Daisy Mae Heath is remembered in Yakama Nation and across Washington for her love of the forest, the land and the spirit of the salmon.

The youngest of nine siblings, Heath grew up in the town of White Swan, nestled in the eastern foothills of the Cascades. The beloved naturalist and athlete went missing in 1987. She was 29.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Heath was one of at least 14 Yakama Nation women who were reported missing or killed.

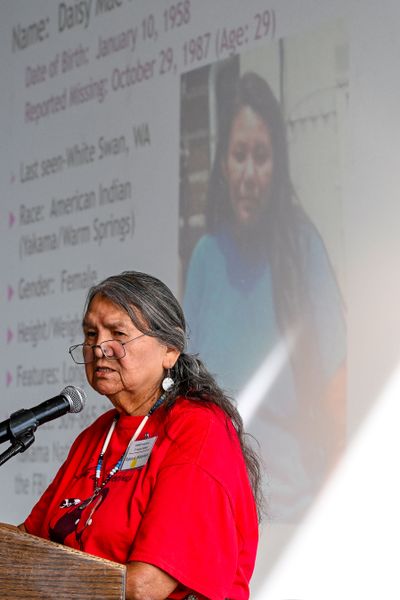

Heath’s sister, Patricia Whitefoot, spoke at an event Wednesday in Airway Heights to honor the lives of thousands of Indigenous women and people who have been reported missing or killed in the United States and around the world.

“Unfortunately, missing and murdered Indigenous Yakama women had begun earlier in the history of the tribe,” Whitefoot said. “Particularly during settler colonial intrusion and military encroachment.”

Wednesday marked the first day of National Native American Heritage Month. It also marked the beginning of Washington’s second annual Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women & People Summit held this year at Northern Quest Resort & Casino. The two-day event organized by a state task force will continue Thursday and feature more speakers, panels and talks of healing.

The event was co-hosted by the Spokane Tribe of Indians, the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Kalispel Tribe of Indians, the Coeur D’Alene Tribe, the Idaho Coalition Against Sexual and Domestic Violence, and the Washington Office of the Attorney General.

Patricia Whitefoot gave the keynote address at Wednesday’s summit.

“Not only on the Yakama Reservation,” Whitefoot said, “but throughout Indian country, it seems like Native women were like bounties. We were to be hunted for.”

Whitefoot, a citizen of the Yakama Nation, described the trauma of losing her little sister as “raw and painful like an open wound.” Whitefoot also shared her anger with law enforcement decades ago at their lack of communication and effort to find her missing sister.

“This has been a sad state of affairs with law enforcement,” Whitefoot said. “I know our family isn’t the only one who has undergone similar circumstances or resistance when talking about MMIWP.”

Heath was laid to rest on Dec. 26. Earlier that year, partial human remains found in November 2008 in a remote area of the Yakama Reservation were identified as a DNA match to Heath. Her death was declared a homicide.

“We have to continue sharing about our loved ones, our relatives who have been murdered and/or missing,” Whitefoot said. “My sister Daisy isn’t the only one. … I don’t want to be a part of the data, but it’s important that we know about the history of our people and who they are and where they come from. So say her name: Daisy Mae.”

Whitefoot said it is her goal to continue her late sister’s vision for truth, justice and healing amongst humanity.

More than 85% of Indigenous women in the United States have experienced violence in their lifetime, a 2016 report from the National Institute of Justice found. About 66% of Indigenous women in the country have faced psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetimes.

Another 56% have experienced sexual violence. And 55% have faced physical violence by an intimate partner, and 48% have experienced stalking.

‘A table that wasn’t built for us’

State Rep. Debra Lekanoff, who represents the 40th legislative district, was another speaker at Wednesday’s event.

In her speech, Lekanoff said she was the only Native American elected official in the Legislature when she took office. She said she was told to act and speak more like her white colleagues.

“Believe me: I was alone,” she said. “… What I bring to the value of the Washington State Legislature is a voice at a table that wasn’t built for us. Our governing bodies of Washington state – of the nation – weren’t built for people who look like me or sound like me. Those tables were built on the backs of our people.”

Lekanoff said she brought up her perspective not to spark anger, but to highlight the importance of pulling a chair up to the table, moving forward, to join ideas from different people.

“We’re not going anywhere,” she said. “And you’re not going anywhere.”

Lekanoff said state attorney general Bob Ferguson was the first person at the Legislature to pull up a chair to include her voice at the state level and support the MMIWP task force. Ferguson was another speaker at the summit Wednesday.

Ferguson submitted a pre-recorded video of himself to be played at the event. He apologized for not making it in person, saying he was at home watching his children. In his remarks, Ferguson commended the work already done by the state’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force, including the creation of the country’s first Indigenous missing person alert and the first state attorney general’s cold case unit dedicated to MMIWP.

“While these are important steps, much more is needed to fully address this crisis,” Ferguson said, “which is the result of generations of harmful policies and actions.”

Toward the end of her remarks, Lekanoff said, “We as Native American women and people have addressed historical trauma our entire lives. This is who we are. But we’re not victims. We’re survivors.”

The summit is set to continue Thursday, with events including a family healing circle, panel discussions, and a speech from former Wyoming State Rep. Andrea LeBeau, a member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe.

The event will be live-streamed on the state TVW website. A full event agenda can be found on the state MMIWP task force website.

More information can be found on the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center website at niwrc.org.