The EPA waited weeks to test for dioxins after East Palestine derailment. Residents and advocates now demand more transparency

EAST PALESTINE, Ohio — Linda and Russell Murphy left an open house at East Palestine High School on Thursday evening with more questions than answers.

The school’s gymnasium has turned into a hub for informational forums for residents impacted by the Feb. 3 train derailment. But the sparsely attended event Thursday, intended to inform residents about preliminary soil sampling results, seems to represent a growing exhaustion felt among residents as they try to pick up the pieces of their lives.

“If you’ve been here over the past couple weeks, you’ll see that the tables are dropping off,” Linda Murphy said. “The attendance is terrible because it can feel pointless. You can’t see what the dioxins will do. You can’t see the cancer coming.”

Earlier this month, the EPA ordered Norfolk Southern to sample for dioxins, a highly toxic, cancer-causing substance, in East Palestine. Residents and advocates are now demanding more transparency around the testing process, which a Norfolk Southern contractor began about a week and a half ago.

Over 100 organizations in Ohio, Pennsylvania and across the country made their concerns known in a joint letter to the EPA. The letter, sent March 13, outlines several recommendations to rebuild public trust and comprehensively address the possible release of dioxins.

The letter, among other recommendations, asked the EPA to conduct the testing rather than Norfolk, to allow the public to weigh in on its sampling plan, to implement medical monitoring and to expand the scope of its testing beyond soil, including farm animals, wildlife and waterways.

One of the letter’s key orchestrators, Mike Schade of Toxic-Free Future, said his organization discovered that Norfolk’s contractor, a Netherlands-based consulting company known as Arcadis, had created a preliminary soil sampling plan on the same day they sent the letter. But Schade said the same problems still stood.

“The sampling plan was developed really quickly, and the EPA signed off on it pretty quickly,” Schade said. “And to date, as far as I’m aware, there wasn’t an opportunity for impacted communities to provide input. So for all those reasons, we decided to still move forward with sending the letter because these issues still remain true today.”

A myriad of questions have swarmed around several toxic chemicals the Norfolk train was carrying when it crashed, including vinyl chloride, which is associated with a rare form of liver cancer and other health effects.

But more than the vinyl chloride itself, public health experts such as Stephen Lester of The Center for Health, Environment and Justice, a Virginia-based nonprofit, are deeply concerned about the byproducts that the vinyl chloride and other chemicals created during Norfolk’s controlled explosion in five hazardous tanker cars.

“That generated a chemical that’s very toxic,” he said. “That chemical traveled in that black cloud into the community. That chemical is referred to as dioxin.”

Exposure to dioxins can cause cancer, reproductive damage, developmental problems, immune effects, skin lesions and other adverse health effects. It’s also a chemical that’s slow to break down once it is in the environment, according to the EPA’s site.

Lester believes dioxins should have been immediately tested for due to the known danger of burning chemicals like vinyl chloride, rather than six weeks later.

“They were actually dismissing it and minimizing, which didn’t make any sense, because it’s well documented that when you burn that kind of chlorinated chemical, you will generate dioxins,” Lester said. “Given that dioxins form on black particulate matter, which that cloud was packed full with, there’s no reason to think it wouldn’t be there.”’

Judith Enck, founder of Beyond Plastics, an initiative that focuses on plastic pollution, has handled environmental crises as a former EPA regional administrator under the Obama administration.

She said the EPA made two mistakes after the derailment. The first, waiting too long to test for dioxins and second, allowing a railroad contractor to lead the testing.

“I know what the EPA is capable of,” she said. “There’s no question they should have been doing this themselves, and not hand it off to the company’s contractor because there’s already deep distrust within the community. The EPA needed to recognize that.”

Schade said Toxic-Free Future did not hear from the EPA until last Tuesday after they followed up on their letter. He said the EPA agreed to meet with advocacy groups to hear their concerns. That meeting has yet to be scheduled.

For now, experts are reviewing the 117-page plan released earlier this month. One area of concern for Lester is that the plan indicated soil sampling would largely depend on “visual inspections” for ash, soot and other remnants of the derailment and chemical burn.

Lester said relying on visual inspections is a highly unusual approach, since the surface soil has been altered since the derailment first happened. Finding residuals or fragments on the ground would not be “very likely six weeks out from the incident,” he said.

Other environmental factors like rain could also push the toxins deeper into the soil, so surface soil collection wouldn’t be adequate. It’s also unclear what detection limit is being used to find the various forms of dioxin, as it can be highly toxic at very low concentrations, Lester said.

Arcadis’ plan did not note any future sampling from water or farm animals, even though Lester said this is standard procedure when looking for dioxin contamination.

“This is a standard experience with dioxin exposure,” Lester said. “Dioxin accumulates in animals. So any cow, goat or animal that would graze on land and grasses where the dioxin settled will be consuming it. That will eventually get into the milk, into the meat, into the cheese. The only way you’ll know is if EPA goes out and does the testing in the places where these questions exist.”

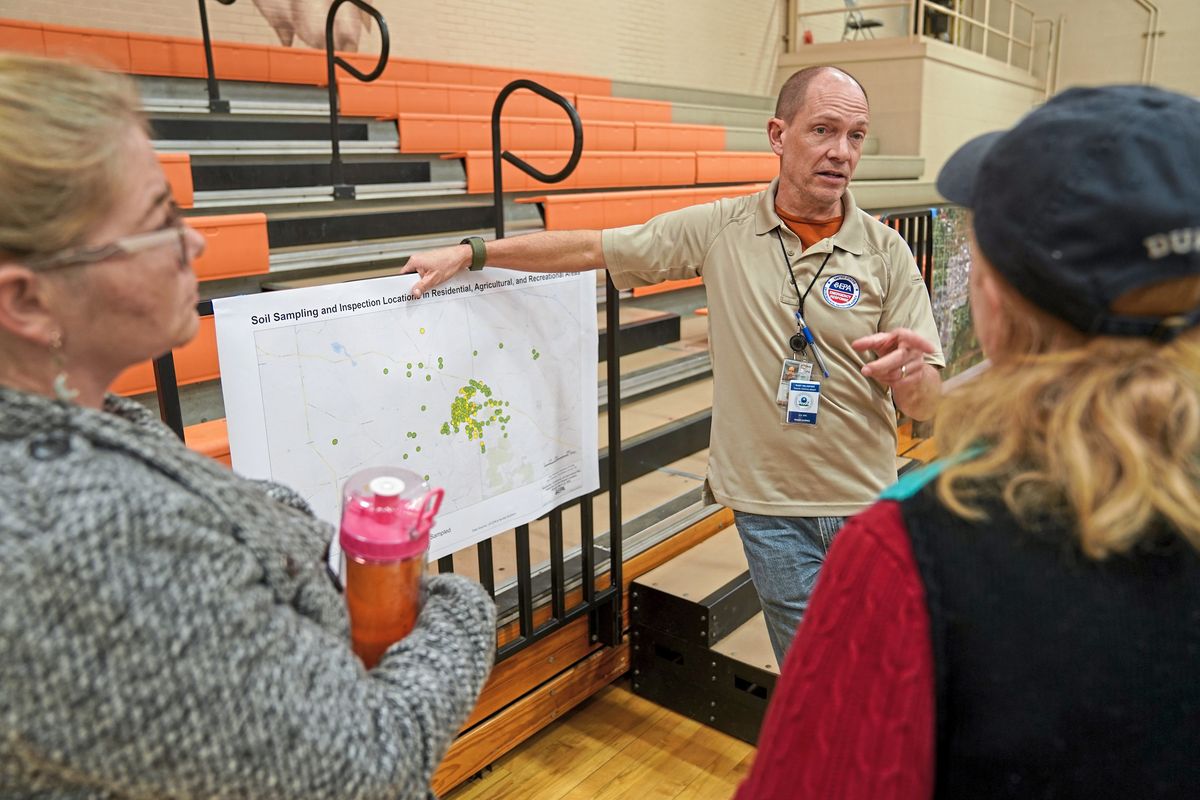

Mark Durno, response coordinator for the U.S. EPA, spent Thursday evening fielding such questions from residents to explain soil sampling efforts.

He said the sampling plan was initiated about a week and a half ago, and the agency wanted to share preliminary results for soil, which was collected mostly from the outskirts of East Palestine, including agricultural parts of Beaver County, to keep the community informed.

Durno said they expect to release the final results in the next several weeks.

“The good news is that all the levels of semi volatile organic compounds and dioxins have all come back with our preliminary results looking like typical background levels in urban and rural areas,” he said.

He said the EPA did not conduct dioxin sampling earlier because they didn’t see the primary byproducts they were looking for after the release, so secondary byproducts like dioxins weren’t a concern.

“We did some analysis to determine whether or not we thought dioxins were a concern, and we didn’t believe there would be an issue,” he said. “However, the community spoke up loudly, and so when a community has been traumatized by an event like this, you do everything you can to help them understand.”

He assured that the visual inspections are not the only determining factor for where they sample soil and that the EPA is closely inspecting Arcadis’ work.

“We don’t have a problem with this contractor,” he said. “But we have to oversee them to make sure it’s being done right. That’s part of our responsibility as a public agency. Hopefully, when all the sampling is done, we’ll be able to say we see no appreciable impacts on this area.”

The Murphys hope for the same outcome for their small community. The couple said they don’t know where to buy hay to feed their horses or whether they will eventually get sick from the grass they graze on. And as planting season comes up soon, the couple is wondering about the food they eat themselves from nearby farms, wondering if the crops will be safe.

“Their train crashed, and it derailed us,” Russell Murphy said. “They need to fix it.”