Builders alarmed about Spokane’s increased development fees. How do they compare?

For months now, Scott Krajack has been waiting to build new homes in Spokane.

Last summer, the land development director at Spokane-based RYN Built Homes had just finished overseeing the development of 20 lots of a projected 94-lot subdivision in the Eagle Ridge neighborhood in Spokane’s Latah Valley. The plan was for 20 homes to be erected before the end of 2022.

Without warning, however, the rug was pulled out from underneath the project. The city of Spokane, citing failing infrastructure that was increasingly burdened by population growth, approved a moratorium of all new residential construction in the Latah Valley while the path forward was decided.

That moratorium expired last Sunday and building on the 20 developed lots is likely to resume in coming weeks. But it’s unclear whether the remaining 74 will ever get built.

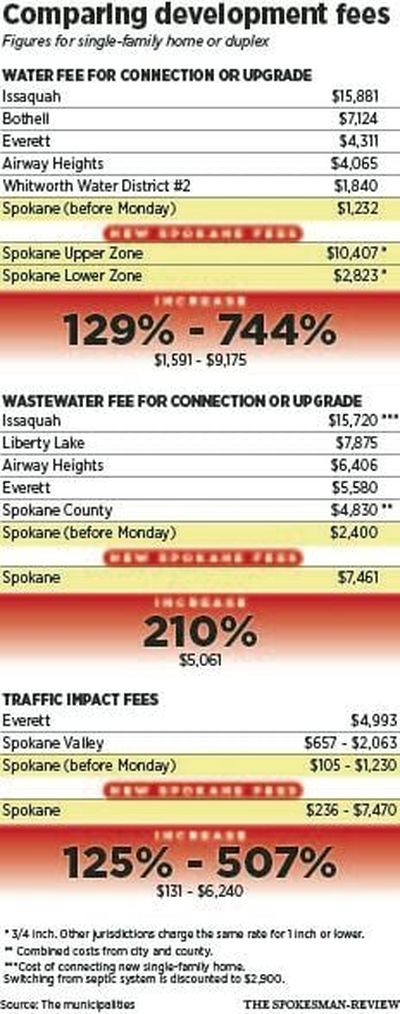

On Monday, the Spokane City Council voted to significantly raise fees for developers who help pay for improvements to water and sewer systems, as well as roads. The fees increased by different amounts depending on the area, with Latah Valley seeing the highest increases.

Developers and realtors balked, warning that the increase would cause new building to screech to a halt when Spokane is already facing a housing availability crisis.

In a Tuesday news release, the Spokane Association of Realtors warned that area builders would shut down 2,000 construction projects that had not yet been permitted, though a list of the projects was not provided.

“March 13th will forever be remembered as the day housing died in Spokane,” said Spokane Association of Realtors President Tom Hormel in the statement.

But how does Spokane’s development fees compare to other cities in the area and across the state?

Traffic impact fees

Among the jurisdictions where they are charged, Spokane’s traffic impact fees were some of the lowest in the state before Monday’s vote.

Transportation impact fees are one-time charges to developers that pay for the increased burden on area roads caused by the new development. They cannot be used to fix existing deficiencies.

The fees differ depending on the type of development and the area of the city. Impact fees collected from a certain area can only go to improve that area’s infrastructure.

After Monday, the most expensive new transportation impact fees, jumping from $1,230 to $7,500 for a single-family home in the Latah Valley, are now the highest in the region, and on par with those found in West Side cities like Bellevue and Renton.

But in downtown Spokane, where more drivers on the roads are most easily absorbed, the impact fees jumped from just $105 to $235. Though they more than doubled, they remain some of the lowest in Washington, according to the Municipal Research and Services Center of Washington.

While Monday’s vote by the Spokane City Council increased fees across the board, it also greatly increased the size of the low-fee downtown area.

In 2021, among cities that charge traffic impact fees, the state average was around $4,750 for a single-family home, which is still higher than anywhere in Spokane outside of the Latah Valley.

Many cities and counties do not charge district-based traffic impact fees, and instead conduct case-by-case analyses of how developments will burden local roads. In Spokane County, that analysis can cost somewhere between $1,000 and $25,000, on top of the actual infrastructure investments that the analysis shows will be needed.

Staff in cities like Walla Walla that rely on individual traffic impact studies are often burdened by the piecemeal nature of those analyses, however. Smaller developments are frequently exempted from that city’s impact studies, because the cost of the analysis could burden the development without significant benefit to the city.

But those waived fees can add up, and a system of transportation impact fees can simplify the calculation. In 2022, Walla Walla started eyeing a switch to that system.

It’s not just small, rural communities making the switch. Seattle and Tacoma, the largest and third-largest cities in the state, also do not have impact fees, but both are undergoing the lengthy process to implement uniform traffic impact fees.

Seattle currently pays for impacts from development through the State Environmental Policy Act and Seattle Department of Transportation permitting processes, wrote Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections spokesperson Bryan Stevens in an email.

Traffic impact fees can be implemented citywide, which allows funds to be pooled for particularly expensive projects, or by district, which focuses the revenue in the area where the development occurred.

Everett, for instance, has a citywide traffic impact fee of $4,993 for a new single-family home. Spokane is now broken up into six districts – seven including airport-controlled land, which is treated differently – with fees ranging from $236 downtown to $7,470 in the Latah Valley.

While Spokane’s districts collectively cover the entire city, Spokane Valley’s three districts cover less than 25% of the city’s land.

Facing failing intersections projected to worsen, Spokane Valley created the three districts in 2021 to staunch the bleeding. Spokane Valley’s fees range from $657 for a single-family home in the Mirabeau area to $2,063 in the North Pines Road area.

General facilities charges

Like the old impact fees, Spokane used to have unusually cheap general facilities charges for new development.

Though those rates increased dramatically Monday, they are for the most part still comparable to similar communities. The Spokane City Council is also considering a possible delay of full-implementation of the rate increase at its March 27 meeting.

Similar to how traffic impact fees pay for improvements to local roads, general facilities charges pay for new facilities that expand water and wastewater systems in the city, such as pump or lift stations. They are one-time fees paid when the development is connected to the city water and sewer system, and cannot be used to address existing deficiencies or pay for ongoing costs.

While builders and developers have balked at the total price tag of Monday’s increases, most of their concern has been pointed at general facilities charges, not impact fees.

Since 2002, the water connection fee had been $1,232 and the sewer connection fee has been $2,400 for a 1-inch water pipe or smaller, which account for 94% of all connections in the city. Charges for both water and sewer connections are calculated based on the size of the water tap pipe.

Not only were these exceptionally low rates for the state, they were also low for the immediate area. Airway Heights charges $4,065 for the water connection and $6,406 for the sewer connection.

Even Spokane County charged more for sewer connections, at a rate of $4,830 for a single-family home through a slightly different calculation than Spokane uses.

Spokane’s general facilities charges increased dramatically Monday. The sewer connection charge jumped to $7,461, a 310% increase, though it remains lower than the $7,875 charged by nearby Liberty Lake. Spokane’s rate is also still significantly lower than those in faster growing cities on the West Side, such as Olympia, Bellevue or Redmond.

Spokane’s water connection fees are now more complicated.

The city has been split into two zones, upper and lower, roughly depending on elevation and the relative cost to provide water and wastewater services.

In the upper zone, including southern and northwestern Spokane, as well as a smattering of smaller areas to the east, fees skyrocketed with Monday’s vote.

From a cost of $1,232 for the smallest connection, connecting a three-quarter-inch pipe now costs $10,407. Connecting a 6-inch pipe for commercial or multifamily buildings jumped from around $18,000 to nearly $470,000.

In the lower zone, fees will increase to $2,823 for a three-quarter-inch connection, but the rate hike won’t take effect until 2024.

Despite the sharp increase, fees in the lower zone remain relatively low for the state and comparable for the region.

Neither Spokane County nor Spokane Valley make developers pay for new water facilities, as they do not provide those services. Instead, developers have to navigate the patchwork of water districts in the area, which have differing rates.

The Whitworth Water District No. 2 north of Spokane, for example, charges $1,840 to connect a single-family home.

The upper zone’s increases are a different story, however. At over $10,000 for the smallest connection, it will cost more than double to connect a single-family home to city services in those areas of Spokane than in Olympia or Everett. Few cities can boast higher rates, among them being Issaquah, Kirkland and Redmond.

Bottom line

Though Krajack has too much money invested in the empty lots on Eagle Ridge to pull out now, he isn’t sure whether the subdivision’s remaining two phases and 74 lots will ever get built.

“If we lose money on phase 1, then we won’t move forward with phase 2,” he said.

The developer is looking tentatively towards the March 27 meeting of the Spokane City Council, when the recently passed increases might be deferred until 2024, with much smaller rate hikes implemented for the rest of the year.

A delay to the beginning of the full fees would at least give developers and builders the opportunity to complete projects already in the pipeline, such as Krajack’s 20 lots.

Still, he isn’t particularly optimistic that the delay will mean any less pain for developers come next year.

“A lot of builders around Spokane are saying we’re going to close up shop,” Krajack said. “Their calculation is, it simply doesn’t pencil anymore to build homes in Spokane.”

Monday’s fee increases tally up to roughly $7,000 more to build a single-family home in downtown Spokane and $16,000 more to build the same home in the Latah Valley.

Realtors emphasize that the fee increases will be passed on to homebuyers, who will almost always pay them with interest through a mortgage.

For a $400,000 home with a 6% down payment, based on current interest rates, a $7,000 increase for developers in downtown Spokane could translate to around $15,000 more in costs during the life of a 30-year fixed rate mortgage, according to the Spokane Teachers Credit Union home loan calculator.

In the Latah Valley area, an additional cost to developers of roughly $16,000 could translate to a nearly $35,000 cost increase during the life of a similar mortgage.