How Is soufflé linked to flatulence? Ask the linguist, not the doctor.

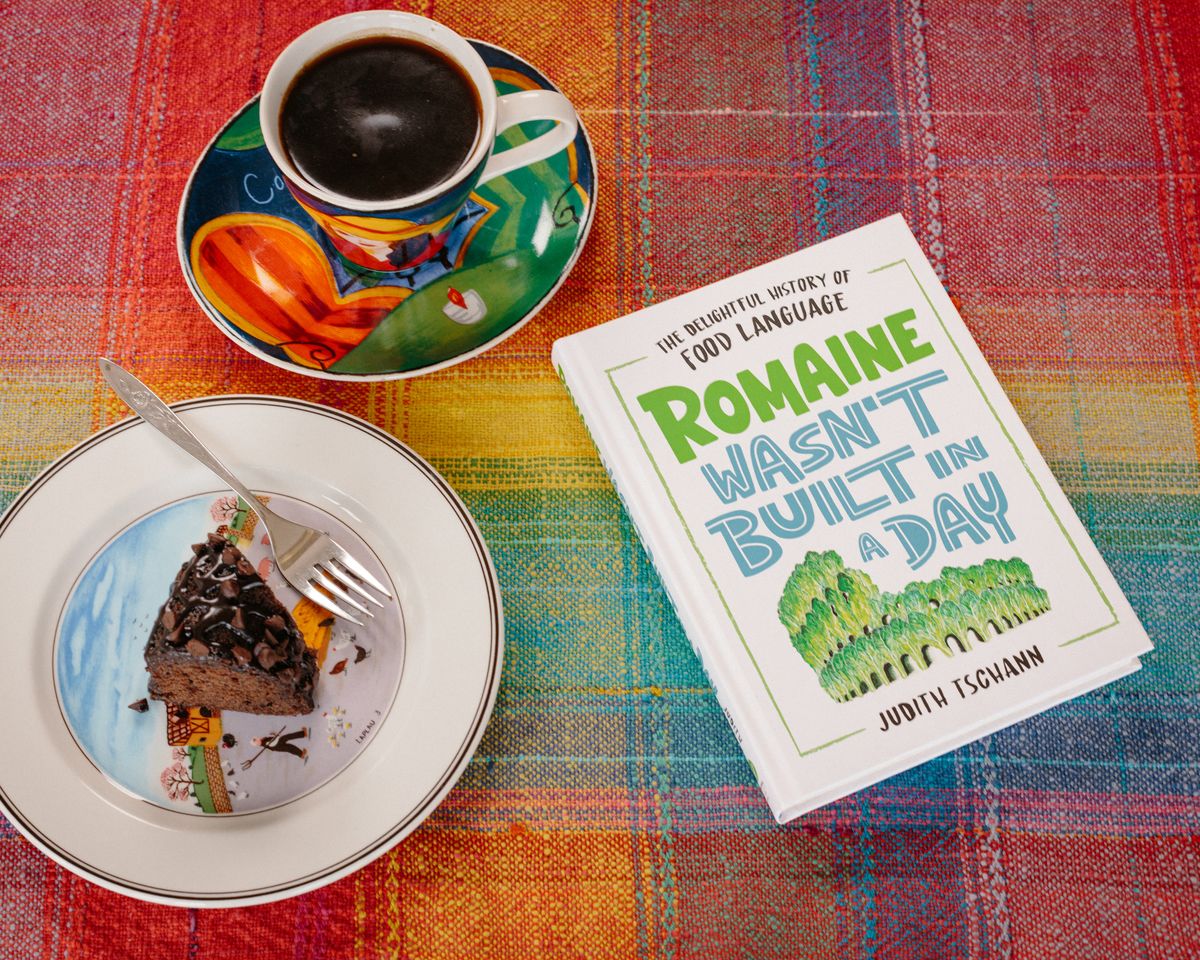

Used judiciously, the snappy tidbits of food etymology in “Romaine Wasn’t Built in a Day,” a new book by the medieval scholar Judith Tschann, could make you a hit at dinner parties.

Say someone shows up in a seersucker suit. You could inform her that the British took the word seersucker from the Hindi sirsakar, which itself came from a Persian word meaning milk and sugar. The smooth stripes are the milk, the bumpy ones the sugar.

Over the Caesar salad, you could casually mention that the English word romaine comes from the medieval French laitue romaine, or Roman lettuce, which possibly arrived in France along with the popes who moved to Avignon from Rome to escape some nasty politics in the early 1300s.

But here’s a pro tip: When sharing food lore at a meal, it’s easy to cross the line. Do your friends dipping into a bowl of guacamole need to know that the word avocado started out as ahuacatl, a Nahuatl term that the Aztecs likely used as slang for testicles? Or that soufflé comes the French word for blown, which stems from the same root as the word flatulent?

“Language is just so amusing. It has playfulness built into it, and so does food,” said Tschann, who taught English and linguistics for many years at the University of Redlands, in California.

The etymologies of food words, she said, are a path through the history of how we eat and cook.

Take the word recipe. It’s the imperative form of the Latin verb recipere, which means to receive or take. In Western medieval and early modern manuscripts, it was used to instruct people how to take medical prescriptions: “Recipe honey with codfish oil,” for example. (Rx is a medieval abbreviation of the word.)

Mushroom first appeared in English at the end of the 14th century, borrowed from the Anglo-French musherum and the Central French moisseron.

“The English lexicon is fat from centuries of sucking up words from other languages,” Tschann said.

Relish came from the Old French relaisser, to release, which came from the Latin relaxare, to relax. The idea is that relish releases flavor, she said.

And that Starbucks mocha you just ordered? Mocha is a toponym – a word derived from a place. In this case, Mukha, a port city in Yemen that handled coffee shipments in the 18th century.

Other toponyms include vichyssoise, from Vichy, France; Tabasco peppers from the Mexican city; bialy from Bialystok, Poland; and lima beans from Lima, Peru (not Lima, Ohio).

Conversely, some geographic names started with food. Topeka may derive from a Dakota word meaning a place for digging potatoes. Chicago comes from the word for wild leek in Miami-Illinois, another Indigenous language.

Food and drink names also slip into common use through a process Tschann calls “coining,” in which a marketing term becomes a generic name. Granola, which today refers to a crunchy cereal with grains and nuts, started as a proprietary name invented by John Harvey Kellogg in the late 1800s.

Compounding is another way food language grows. Bibimbap comes from the Korean pibim (to mix) and pap (rice). The espressotini is a mix of espresso and vodka.

The martini, by the way, was originally named for Martinez, a town in California where the drink was developed for Gold Rush miners. At some point, the Italian vermouth maker Martini & Rossi elbowed its way in and the “ez” fell away.

Food words are sometimes adopted by pursuits that have nothing to do with food. Consider the world of computing, which uses a menu to navigate selections. The first portable computer, introduced in the late 1980s, was called a lunchbox. Some developers of the 1990s programming language claim they called it Java because of all the coffee they drank while creating it. Cookies, chips, hosts and servers have all settled nicely into computer language and, increasingly, social media.

Tschann is careful to offer caveats when caveats are due. No one really knows if balls of fried cornmeal batter are called hush puppies because they were tossed to howling hounds to shut them up, or if pie came from cooks who observed magpies filling their nests with a collection of disparate objects.

Was the Reuben sandwich named for Reuben Kulakofsky, a Nebraska grocer in the 1920s and ’30s? Or was it based on the Reuben’s special, which Arthur Reuben created in 1914 at his New York City delicatessen?

Whatever the case, there are plenty of established facts to hang one’s dinner napkin on.

Taco is a 20th-century word from Mexican Spanish that means plug or wad, a reference to part of an explosive used in silver mining.

Ceviche is likely from Quechuan, the language of the Inca Empire, where people used the word siwichi to describe fresh or tender fish.

Barbecue comes from barbacoa, a word in the Arawakan language of the Caribbean that describes a wooden frame for sleeping on and drying food.

Fans of the Broadway musical “Six” might like to know that the Bloody Mary is named after Mary Tudor, the daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. (As Queen Mary I of England, she burned Protestants at the stake in an effort to reverse the Reformation, initiated by her father.) The first recorded use of Bloody Mary to describe a drink was in 1939, when a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune declared it “the new pick-me-up.”

The evolution of the word cocktail is one of Tschann’s favorites in the book. It comes from the docking of a horse’s tail, which then stood up like a rooster’s and was referred to as a cock-tail. Thoroughbred racehorses did not have their tails docked, but if a horse had docking in its lineage, it was considered of mixed breed. By the 19th century, cocktails had come to mean mixed drinks.

She is also fond of junket, like the kind of trip a politician might take. It derives from the French jonquette, a sweet made with boiled milk, which has connections to the medieval Latin joncata, a type of soft cheese. In English, junket came to mean sweetened curds.

She can’t pinpoint exactly how cocktail made the leap to a beverage and junket made the leap from food, though. Language is always changing, and accounting for semantic evolution is not always possible.

That can be challenging for Tschann when she finds herself at a party.

“When you’re studying the history of food words, people can pepper you with questions,” she said. “They ask me the etymology of a word, and I have to think about it way too long. I feel oddly tongue-tied.”