Lewis-Clark State College removes artwork about abortion, citing a state law

Artwork about abortion is, historically speaking, vanishingly rare. And the future display of such work seems dimmer after a small public college in Idaho removed six works about abortion and birth control from an exhibition, citing a state anti-abortion law.

Lewis-Clark State College in Lewiston removed the works days before the opening this month of “Unconditional Care: Listening to People’s Health Needs.” The school’s Center for Arts & History described its show as an exploration of “today’s biggest health issues” through the stories of those affected, including “chronic illness, disability, pregnancy, sexual assault, and gun violence and deaths.”

Several national civil rights organizations have criticized the school’s decision or the state law it was trying to navigate.

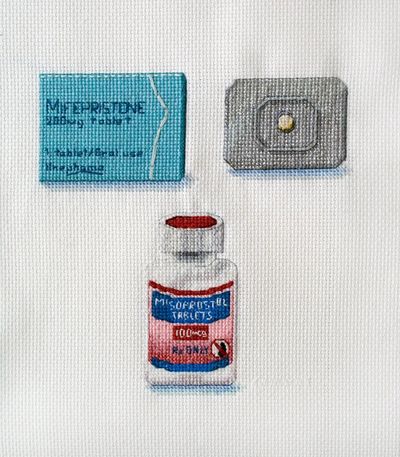

Three artists had their work taken down, including Katrina Majkut, the show’s guest curator. Her censored work is an embroidery that depicts bottles of mifepristone and misoprostol, medicines taken in conjunction to end a pregnancy; accompanying wall text explains their efficacy and state laws governing their use.

“I’ve shown this work in red and blue states,” Majkut said. “I’ve never had a problem. Never heard a peep.”

Majkut says the college also informed her, hours before the opening, that exhibiting wall text explaining Idaho’s abortion laws was not permissible.

“You can be against or for abortion, but the goal of the artwork, and the exhibit at large, is to discuss difficult topics with mutual respect and empathy,” she said.

Idaho’s No Public Funds for Abortion Act, which was enacted in 2021, a year before the U.S. Supreme Court overruled Roe v. Wade, prohibits state funds from being used to perform, “promote” or “counsel in favor of” abortions. Penalties include fines and jail time.

A Lewis-Clark spokesman said in a statement that the school “became aware of concerns” about the exhibition on Feb. 26 and was then informed by its legal counsel that “some of the proposed exhibits could not be included.” The spokesman did not answer questions about who raised the concerns over a show that was not yet open to the public. Emily Johnsen, director of the Center for Arts & History, did not respond to a request for comment.

The artists Michelle Hartney and Lydia Nobles also had works removed from the show at Lewis-Clark.

Hartney’s work is a print of a handwritten transcription of one of the thousands of letters written a century ago to the Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger by women pleading for information about birth control at a time when federal Comstock laws prohibited using mail to circulate material defined as “obscene and illicit.” Contraception was singled out as an example.

“The letter writer simply mentions having had an abortion in the 1920s,” Hartney said, “but the larger project that it’s part of, called ‘Unplanned Parenthood,’ is not about abortion, and that is by design. It’s about the history of birth control access in the U.S.”

A series by Nobles, “As I Sit Waiting,” presents video and audio of interviews with women about their experience with access to abortion, as well as sculptures that resemble abstracted waiting room chairs. Three videos and an audio recording were removed from the exhibition.

Nobles said she was not sure how to answer when Johnsen, the center’s director, asked her in late February whether her work promoted abortion. “My work presents unbiased, first-person accounts,” she said.

Criticism of the school’s decision was pointed. The Idaho Statesman published an editorial decrying “a regime of censorship,” and PEN America called the removal of Nobles’s work “a slap in the face to artistic and academic freedom.” The American Civil Liberties Union and the National Project Against Censorship sent a letter to the school’s president, Cynthia Pemberton, that says the decision to remove Nobles’s work threatens a “bedrock First Amendment principle.”

Pemberton did not respond to a request for comment.

Scarlet Kim, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU who signed the letter, said in an interview that Idaho’s law was “deeply troubling and scary” and was chilling speech at its public universities. She compared it to a wave of legislation against discussing critical race theory in schools, which she fears could be used to censor artworks about race.

“Speech that is favorable to abortion can be a part of academic discussions about science, medicine, philosophy and gender equality,” she said.

Hartney, one of the affected artists, said, “Sanger did get arrested for giving people information, and in the same way, the government is trying to silence us now.” She continued, “These women’s voices from the past are important.”