Defending Ukraine’s ‘highway of life’ - the last road out of Bakhmut

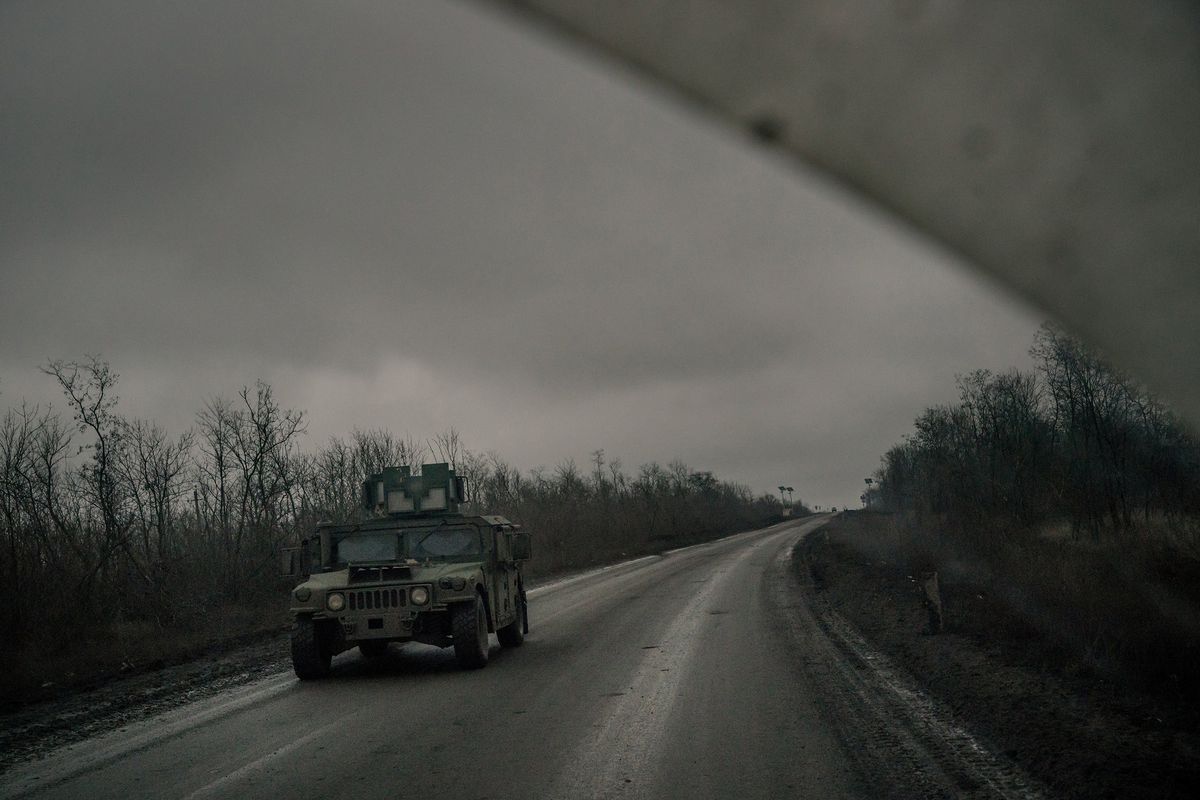

KOSTYANTYNIVKA, Ukraine – The battle for Bakhmut raged behind them, but the tank crew had a more immediate concern: finding a patch of asphalt on the last viable road out of the embattled city to fix their clattering T-64 without falling into a quagmire of thigh-high black mud.

The tank engine quit its smoky growl on a solid chunk of Highway T0504, and two crewmen leaped off to inspect the tracks. They had run over an explosive in the neighboring village of Ivanivske, a soldier explained, adding a string of expletives, and needed to make quick repairs to return to the fight. With thwacks of a spade and clinks of a hammer, the crew popped off a few teeth inside the tread. One soldier suggested slowly driving forward to check the gears were properly seated.

“What do you mean slow?” another snapped back. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.” The driver smoked a cigarette as armored vehicles raced past them toward the razed eastern city, where the war’s bloodiest battle churns on.

Russia has committed hordes of soldiers and mercenaries to capturing Bakhmut. Those fighters have pushed Ukrainian troops to the city’s western edge and, like an alligator’s maw, are closing in from the south and north, aiming to encircle and annihilate them.

The maneuver has cut off virtually all roads – except Highway T0504, a two-lane hardball that connects to Bakhmut’s southwestern edge and is so vital that troops have branded it “the highway of life.”

“It’s the only road left in which we can evacuate the wounded, evacuate the dead,” said Maj. Oleksandr Pantsernyi, the commander of the 24th Separate Assault Battalion, one of the units responsible for defending the corridor. Just as important is the road’s role in sustaining the fight, he said, by enabling the movement of ammunition, water and fresh troops east.

“If we don’t do our job, the defense of Bakhmut will last for a day or two,” Pantsernyi, 26, said. “And all people who are there will stay there forever.”

Russia’s forces also know the road’s importance, Ukrainian soldiers said, and have tried to shred it with artillery and force their enemy into the mud. Although there is another pathway that branches off from T0504 and curves northwest out of the city, soldiers said that road hems too close to enemy lines and indirect fire. Using it, they said without irony, is “Russian roulette.”

The 24th has pummeled Russian positions with aging Soviet howitzers and fought soldiers inside trenches at fisticuff range. The unit also trains at nearly every available moment. It helped support a massive operation involving thousands of soldiers Thursday and Friday, as machine-gun fire and howitzer shell explosions rolled across the coal-packed hills in service of a crucial objective: to pry the alligator’s jaw open.

The laser focus on Bakhmut has drawn skepticism on both sides. Russia is intent on taking it to claim a victory after a row of setbacks, while Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has turned the stubborn defense of the city into a rallying cry.

While Bakhmut sits along key roads and railways in the Donbas region, control of the city is unlikely to tip the war’s outcome. The benefit to Ukraine of killing waves of Wagner mercenaries and Russian soldiers may not outweigh the cost of its own steep losses, given that Kyiv needs resources for an anticipated spring offensive.

But orders are orders, and the 24th is here to fight until Russia retreats, or until everyone is dead.

A lieutenant with the call sign Hook held court with a platoon of soldiers wielding plastic airsoft guns to teach them how to assault buildings in open terrain. Teams of two took cover in the rubble of a chemical factory, then ran into a garage. “Move! Move! Move!” Hook shouted. The soldiers quickened their steps, suppressing phantom gunmen with volleys of plastic pellets.

Like most troops in Ukraine, he and other soldiers interviewed are being identified by their call signs because they were not authorized to disclose their full names to journalists.

Some troops in Hook’s command have little combat experience, he said, although the battle in and around Bakhmut has provided quick and brutal wisdom. A former sales manager, Hook, 33, constantly analyzes how Wagner forces order their attacks and flanking maneuvers, then prepares his men to zig when they zag.

“I love to fool them,” he said, “and make a fool of them.”

But Hook and others in the battalion also voiced frustrations over ammunition and weapon shortages.

While Western backers proclaim that they are streaming equipment into Ukraine, soldiers said the supply becomes a trickle when the gear is doled out – even at the epicenter of fighting closely watched by senior Ukrainian officials. This has made their task of holding the road and stifling Russian advances harder and riskier, they said.

A surveillance-drone operator called Aviator said the battle for the skies has come down to commercial equipment often sourced from China. He uses a DJI Mavic 3 drone to search for enemy positions and patch in live video for artillery commanders so they can refine strikes in real time.

The Russians, in turn, have a DJI device that can detect his drone’s flight path and launch location – information used to fire at Ukrainian positions, he said.

Russian troops also wield a Chinese-made device that can sever the link between his controls and the drone, Aviator said, forcing him to get close to enemy positions to maintain a strong signal. That puts him in range of mortars and snipers, were he can feel the organ-rumbling crash of howitzer strikes.

Aviator and other drone operators pipe their feeds to a dimly lit farmhouse turned command post in the Donetsk region. Inside, soldiers rest their Kalashnikovs against the wall, drink coffee from plastic cups and comb over videos on two big-screen TVs.

Chichen, 26, an artillery battery commander, his brow furrowed and pierced, constantly shifts between his phone, tablet and the aerial shots of Bakhmut’s apocalyptic landscape, looking to turn more Russian positions into smoldering rubble with his set of four D-30 howitzers.

The Bakhmut battle has taken a toll on the unit, he said. Of about two dozen assault operations in the area, only one ended without casualties. The darkest day, he said, involved an operation northeast of the city in the fall that left more than 150 soldiers dead, wounded or missing. “Even if you win, you still lose,” he said. “You go in knowing it will be hell.”

Compounding the difficulties, Chichen said, was the condition of the artillery pieces, which are twice as old as Chichen, ground down from use and repaired at least 10 times already, making them less reliable with every volley.

Then there is the ammunition. Artillery is a delicate skill, with cannoneers assessing topography, air pressure and even the weather at the top of the round’s parabolic arc before taking a shot. Another variable, Chichen said, is the shell’s fuze and explosives, which vary according to where they are made. The unit has had shells from Pakistan, the Czech Republic and elsewhere, soldiers said.

And there are not enough shells. At the start of the invasion, Chichen said, he would fire about 300 rounds a day. Now, it’s closer to 10 a day, with far more targets than the ammunition needed to hit them.

But Chichen and his men did not dwell much on limitations Friday, or become distracted by Zelenskyy’s honoring of 24th soldiers as heroes of Ukraine. His howitzers were trained on the southwest edge of Bakhmut, where the T0504 cuts into the city. Drones buzzed in the air, hunting for the enemy.

Clear setbacks were present during the mission. The drone feed captured an enemy strike on Ukrainian forces, and there were soon reports of wounded. “Oh, (no),” a soldier cursed, with the resignation of someone who had seen such a moment before.

Another explosion flashed on screen at a house where Russian forces took shelter. The soldiers watching erupted in cheers twice; during the initial hit, and again after a second feed on a delay showed a different angle, like a touchdown replay.

A soldier who watched it all, known as Happy for his joyful demeanor under fire, described the euphoria. “What better feeling is there,” he asked, “than killing a Russian?”