Bob Richards, pole vaulter who landed on Wheaties boxes, dies at 97

Bob Richards, an ordained minister who became the first athlete to appear on the front of a Wheaties box after he won two Olympic gold medals in the pole vault during the 1950s, an accomplishment he parlayed into a successful career as a motivational speaker, died Feb. 26 at his home in Waco, Tex. He was 97.

His daughter Tammy Richards LeSure confirmed the death but did not cite a specific cause.

Known alternatively as the “Vaulting Vicar” and the “Pole Vaulting Pastor,” Mr. Richards was one of the most dominating athletes of his time, leaping as high as 15 feet 6 inches with a stiff metal pole in the days before flexible fiberglass helped Olympic vaulters cross over bars nearly 20 feet in height.

In addition to the gold medals he won at the 1952 Olympics in Finland and the 1956 Games in Australia, Mr. Richards won 17 national pole vault championships and was ranked No. 1 eight times in an era when pole vaulting and other Olympic track-and-field events were chronicled on the front page of sports sections.

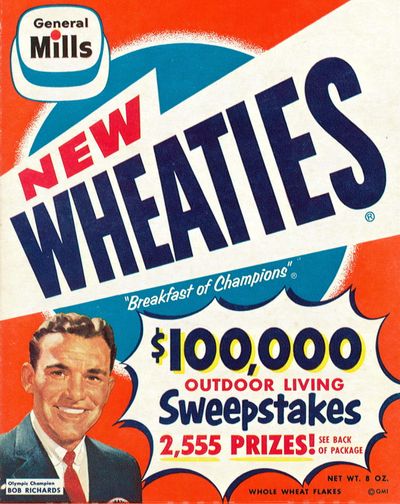

His success in the air, combined with wholesome looks and an upbeat ministerial eloquence, made Mr. Richards a fixture in American households. In 1957, he played himself in “Leap to Heaven” on ABC’s “DuPont Cavalcade Theatre” in a dramatization of his life. A year later, General Mills tapped him as its pitchman on the front of Wheaties cereal boxes and in television commercials.

By then, Mr. Richards was hopscotching around the country delivering what would add up to more than 25,000 motivational speeches at sales conferences, awards dinners and corporate retreats.

“One recent night,” Sports Illustrated wrote in 1968, Mr. Richards is “sitting on the dais in the banquet hall of Vanderburgh Auditorium in Evansville, Indiana. It is a Monday night, and he is to address the annual awards dinner of the Evansville Sales and Marketing Executives Club, attended by some 200 salesmen and their ladies.”

Eighteen salesmen received awards. Then, for the next hour, the floor was his.

“In a matter of minutes he has the Evansville salesmen in his grip. His eyes shut tightly, his hands knifing through the air, he carries the salesmen to successive peaks of grim determination,” Sports Illustrated noted. “Bobbing and weaving, his forehead glistening with perspiration, he is Rocky Marciano on the attack against Archie Moore. He is Bart Starr on third down.”

Mr. Richards told them, “I want to set you on fire; I want to get you to go, to act.” And: “You’ve got to go through that line, you’ve got to figure out ways to beat the opposition. The salesman is on the field! He’s out there in the middle of the fight.”

Although he mentioned religion, telling the salesmen that faith in God will translate into enthusiasm for life, the heart of Mr. Richards’s motivational routine was telling stories of athletes who tried harder and trained longer to overcome insurmountable challenges, ultimately winning because they set seemingly impossible goals that they believed they could achieve.

“I say this and don’t say this to be humble,” Mr. Richards said in a recorded speech sold as “There’s Genius in the Average Man,” “but I reckon that there were over a million guys in America who could have beaten me in both Olympic Games.

“A million guys stronger, faster,” he continued. “But they didn’t believe they could win the Olympics. They had never gotten on a track. They had never tried. Your capacity is only discovered, ladies and gentlemen, in challenge. And the bigger your challenge, the bigger you become as a person. If you’ve got a little tiny goal, a little tiny challenge, you’ll never make it.”

He brought up the boxer Cassius Clay, later known as Muhammad Ali, who was famous for saying, “I’m the greatest!”

“You know how important it is to feel that way about yourself?” Mr. Richards said. “To feel that you’ve got it? Most of us say, ‘I’m the worst. I can’t do anything. I’m terrible.’ We wonder why we don’t do anything when we don’t believe we can. Can you imagine going into a boxing ring thinking, ‘Maybe I’m not the greatest?’”

The third of five children, Robert Eugene Richards was born in Champaign, Ill., on Feb. 20, 1926. His father worked as a telephone lineman, and his mother was a homemaker.

Growing up, he excelled in sports. He dove. He played basketball. He started at quarterback for his high school football team. But pole vaulting, which he took up in junior high, was his obsession. He built a pit in his backyard, jumping over a crossbar set between a tree limb and phone pole.

He got into some typical teenage troubles in high school, but was set straight by a minister of the Church of the Brethren. With the minister’s help, Mr. Richards enrolled at Bridgewater College, a Brethren-affiliated school in Virginia, where he dominated collegiate pole vaulting.

When he turned 20, Mr. Richards was ordained in the Church of the Brethren. He transferred to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he graduated in 1947, the same year he tied for first in pole vaulting at the NCAA championships.

The next year, he competed with the U.S. Olympic team in London, winning a bronze medal. In 1951, he became the second pole vaulter to clear 15 feet. (The first was Cornelius “Dutch” Warmerdam.)

Mr. Richards started but didn’t complete a doctorate in philosophy. In between pole vaulting competitions, he taught at LaVerne College, a Brethren-affiliated school in Southern California. After winning a second goal medal, Mr. Richards’s career as pitchman took off, buoyed not just by Wheaties but also his popular 1959 autobiography “Heart of a Champion.”

During his travels, Mr. Richards became frustrated that the American Dream was slipping away for farmers and blue-collar workers struggling to buy homes and hold steady jobs. In 1984, saying the country “must work to get rid of these tyrants who rule us,” he ran for president on the Populist Party ticket.

The Populist Party sought to abolish income taxes and the Federal Reserve Bank. But it also came to be known for the far-right extremist views of one its founders, Willis Carto, a Holocaust denier and neo-Nazi hero. Mr. Richards’s daughter said her father regretted running on the Populist Party ticket “given the extremism that developed in the party.”

Mr. Richards’s 1946 marriage to Mary Leah Cline ended in divorce. In 1970, he married Vonda Joan Beaird. She died in 2019.

Survivors include three children from his first marriage, Carol Stasiewicz of Reno, Nev., Robert Richards Jr. of Garden Grove, Calif., and Paul Richards of Waco, Tex.; three children from his second marriage, Brandon Richards and Thomas Richards, both of China Spring, Tex., and Tammy Richards LeSure of Mansfield, Tex.; a brother; and 31 grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Mr. Richards is still the only Olympic pole vaulter to win two gold medals, but he’s not the family’s lone record holder. Several of his children and grandchildren became competitive pole vaulters, surpassing his 15 feet 6 inches by several feet - though they weren’t vaulting with a metal pole.

“If you want to get a clear picture,” Mr. Richards once said, “give today’s vaulters a stiff pole.”