Book World: A guide to Cormac McCarthy’s bloody, brutal fiction

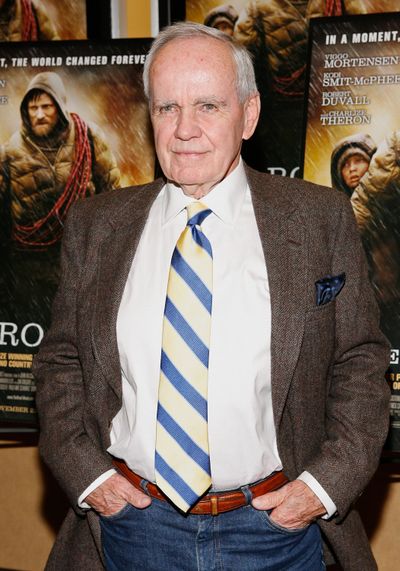

Cormac McCarthy, who died on Tuesday at 89, was a great American novelist who tackled what he regarded as great American themes: history, violence, the nature of evil, the myth of the West. His 12 novels, which remodeled the cheap set pieces of genre – especially the Western and the crime thriller – were exceptionally bloody. He wrote in two stylistic modes, per New Yorker critic James Wood: His prose could be flat or ornate, terse or maximalist. (In all cases, he tended to eschew commas.)

McCarthy stayed out of the limelight. In 2022, he published his first novel in 16 years, “The Passenger,” which he’d long alluded to working on. Its contents marked an unusual departure for him, in some respects. “I was planning on writing about a woman for 50 years,” he once said. “I will never be competent enough to do so, but at some point you have to try.” The Washington Post’s Ron Charles warned fans: “Prepare to be baffled.”

Here’s a quick guide to McCarthy’s essential work:

The essentials

“Blood Meridian” (1985). It would be hard to decide on McCarthy’s most violent novel, but this one is a strong contender. It’s arguably his most renowned novel, featuring his most (in)famous character, Judge Holden, who leads a gang in massacres across the Mexico-Texas borderlands, dancing all the while. In his review for the Post, Jonathan Yardley summarized the plot this way: “A bunch of men ride around for a while, they camp for a while, they philosophize for a while, they kill for a while. It’s all in a day’s work, but it sure makes for a slow day.” The critic Harold Bloom, though, once declared it “the ultimate western,” solidifying McCarthy as “the worthy disciple both of Melville and of Faulkner.”

“Suttree” (1979). In his fourth novel, McCarthy in part draws on his own life, turning his eye to often-dissolute river-dwellers in Knoxville, Tenn. Though contemporary critics were sometimes skeptical, it attracted attention in part for its often expansive language. “At times Mr. McCarthy’s picture of hell becomes bloated and strained with thick, gassy language,” Jerome Charyn wrote in his review for the New York Times, before adding: “But the bombast disappears as quickly as it arrives, and Mr. McCarthy creates images and feelings with the force of a knuckle on the head.” The Post’s review, meanwhile, compared the novelist to “some latter-day Virgil with an unabridged dictionary” who “guides us with his images through the netherworld.”

“All the Pretty Horses” (1992). The first installment of the Border Trilogy, this is McCarthy at his most accessible and his most classicizing: There’s a 16-year-old boy (John Grady Cole), his horse and the road to Mexico; there are friends who die, and a girl who breaks his heart. The Post’s reviewer said at the time that it “has as much action and excitement as a Zane Grey story,” without sacrificing literary ambition: “In an age of TV, he is its antithesis. He is moonshine whisky, clear and raw and potent, in a world more accustomed to Lite Beer and Diet Coke.”

“The Crossing” (1994). The sequel followed a different group of teens – this time, brothers Billy and Boyd Parham – on their journey south. This novel explores ecological themes as expressed in encounters between humans and animals: Its richest, strangest central relationship is between Billy and a pregnant wolf. “Some women found ‘Pretty Horses’ boringly macho, too much a boys’ adventure,” the Post’s Michael Dirda wrote in his review. “This one may remind them, at times, of a magic-realist issue of Field and Stream.”

“The Road” (2006). Arguably McCarthy’s first, oblique foray into science fiction, this brief, bleak novel follows a father and son’s struggle to survive after an unnamed apocalypse. “ ‘The Road’ is a frightening, profound tale that drags us into places we don’t want to go, forces us to think about questions we don’t want to ask,” the Post’s Ron Charles wrote in his review. Many readers might dismiss McCarthy’s grandiosity, he continued: “At first I kept trying to scoff at it, too, but I was just whistling past the graveyard.” For his part, director John Hillcoat, who adapted “The Road” for the screen in 2009, read it as a story of hope, he told the Post’s Travis M. Andrews in January. The novel won the Pulitzer Prize in 2007.

The early novels: “The Orchard Keeper” (1965), “Outer Dark” (1968), “Child of God” (1973). McCarthy’s first three novels had, if possible, an even darker, more harrowing vision of humanity and its place in the universe than his later work did. “Child of God,” in particular, which James Franco adapted into a feature film that the Post called “nauseating” (but also “mesmerizing”), will test a reader’s stomach for staring into the void.

For the hardcore fans and determined completists

“The Gardener’s Son” (1977). McCarthy tried writing for television long before it became a respectable (and these days, coveted) pursuit for novelists. What was initially pitched as an episode of the series “Visions” ended up as a TV movie about a young man who becomes enraged at the boss of a local cotton mill.

“The Counselor” (2013). Though many of his novels were made into movies, this crime thriller about a lawyer in way over his head was one of McCarthy’s few screenplays. You can read an excerpt, which ran in the New Yorker – but it undersells the luridness of what ended up on screen under the direction of Ridley Scott, including an indescribably lewd scene starring Cameron Diaz. Still, the florid dialogue is unmistakably McCarthy.

“The Kekulé Problem” (2017). Many novelists pursue a sideline in reviews or nonfiction; McCarthy wasn’t one of them. But he had a long-standing connection with Santa Fe Institute, where he had an office, and enjoyed talking about science and philosophy with the researchers over lunch and tea. This odd, ponderous essay, contemplating the unconscious mind, grew out of conversations with one of those colleagues, evolutionary biologist David Krakauer.

The interviews and profiles

McCarthy rarely spoke on the record. The two major profiles – one from 1992 in the Times, and another from 2005, which ran in Vanity Fair – were both by Richard B. Woodward, whom McCarthy got to know over the decades. (He attended Woodward’s wedding.) A third, which ran in the Telegraph in 1994, is an epic write-around, ending with reporter Mick Brown finally finding the writer eating soup at a family restaurant in El Paso, only to be told: “I’m sorry, son, but you’re asking me to do something I just can’t do.”

In 2022, two scholars, Dianne C. Luce and Zachary Turpin, made headlines when they unearthed at least 10 interviews McCarthy gave to local papers in Kentucky and Tennessee between 1968 and 1980. He told the Maryville Alcoa Times in 1971: “My ideal would be to be completely independent. If I could, I’d have a small mill to generate our electricity. But you have to compromise.”

Here is what’s out there:

His appearance on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” 2007: On the occasion of “The Road” being selected for Oprah’s Book Club, McCarthy sat down with the television host and opened by saying he didn’t make such appearances often. “You spend a lot of time thinking about how to write a book, you probably shouldn’t be talking about it. That’s my feeling,” he told her, with a small smile. “You work your side of the street, and I’ll work mine.”

His interview with the Wall Street Journal, 2009: McCarthy, promoting the movie adaptation of “The Road” alongside the director, revealed, among other things, that the only signed copies of the novel – some 250 in all – belonged to his son John, who was free to sell them one day to fund his adventures.

”Couldn’t Care Less” (2017). This documentary captures the writer speaking at length (an hour and 15 minutes!) with Krakauer about math, architecture and more.

Jacob Brogan and John Williams contributed to this report.