Timeline of Camp Hope

A timeline of the Camp Hope homeless camp in east Spokane.

Color Scheme

1 of 2

In late May, the city of Spokane and Washington state agreed that Camp Hope, where fewer than 20 people remained, would close by the end of June. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVI)

On Dec. 10, 2021, as the weather grew freezing, dozens of tents were erected in front of Spokane City Hall to protest the scarcity of low-barrier beds for the homeless, the kind anyone could access despite addiction, mental illness or other obstacles.

An annual point-in-time count conducted a few months later would tally 1,757 homeless people living in Spokane County, primarily living within the city, of which 823 were living without shelter. Other estimates suggest the homeless population was closer to 14,000.

When the protest began, there were 52 low-barrier beds available throughout the city, the low-barrier House of Charity had been closed due to a norovirus outbreak, and 20 hotel vouchers offered by the city had all been claimed.

It was the second time in three years that a protest camp had popped up in front of City Hall. In 2018, after the weeklong hunger strike by activist Alfredo LLamedo, two dozen tents popped up around him as others joined his protest against a lack of 24/7 shelter, as well as the enforcement of anti-camping and sit-lie laws that criminalize homelessness. They dubbed the impromptu encampment “Camp Hope,” a name which protesters would adopt in 2021.

Mayor Nadine Woodward, who had expressed deep skepticism of shelter-first approaches to homelessness while campaigning for office, included funding for a low-barrier shelter in her proposed 2022 budget. The proposal would culminate 10 months later in the opening of the city’s largest shelter in a former trucking warehouse on Trent Avenue, but at the time, few details had been worked out, save that it would be located away from downtown.

Julie Garcia, the controversial founder of homeless services provider Jewels Helping Hands, whose constant demands for better conditions for Spokane’s unhoused population had led her to clash with the city and other organizations in the past, was again leading the charge.

“What we’re asking the city is: could they provide something?” Garcia said at the time, wielding a sign that detailed Spokane’s dearth of low-barrier beds. “These guys have nowhere to safely exist, everywhere they go it’s criminalized, just sitting down somewhere.”

As the protest grew to more than 100 people and dragged on into its fourth day, city officials gave 48 hours’ notice to remove their tents. City spokesman Brian Coddington claimed the demonstration posed health and safety risks and had impacted access to nearby businesses and City Hall itself.

Coddington had argued the notice was for removal of protesters’ property, not the protesters themselves. Woodward, however, indicated she felt the protest had gone on long enough.

“This is a protest. They’ve had sufficient time to make their cause heard,” Woodward said.

On the sixth day, under threat of legal enforcement, all but a few protesters packed their tents up amid a steady snowfall. Advocates at the time suggested that the city’s notice would do little but move the campers elsewhere. Garcia offered to oversee a temporary tent city through the winter, but city officials expressed little interest.

Jewels Helping Hands helped dozens of people haul their tents and possessions elsewhere. Garcia said in an interview that she had been looking for somewhere large enough to accommodate everyone who came along, while also being as far away from houses as possible.

She settled on a barren lot near Freya Street and Interstate owned by the Washington State Department of Transportation cleared about a decade ago to make way for the North Spokane freeway. Garcia later said she thought it was city-owned. Before the day was out, the state patrol issued a 72-hour notice to vacate.

But the 72 hours came and went. Twelve days after the protest began, with 82 people at the new camp, WSDOT announced that, although it planned to disband the small tent city, it would not immediately clear it with law enforcement.

Weeks passed. In mid-January, WSDOT posted another 48-hour notice to vacate. But amid discussions with the city of Spokane to explore short-term options to rehouse the campers, the notice was rescinded.

Two weeks later, Jeffrey Brown, 53, was found dead at the camp after an overdose, according to the Spokane County Medical Examiner.

The camp continued to swell. By mid-March, the entire undeveloped block, which had by then been given the “Camp Hope” moniker of the earlier protests, was filled with tents and vehicles and the population had grown to 300. The state Legislature approved $45 million to remove homeless encampments from state right-of-ways, including Spokane’s.

Plans for Woodward’s signature homeless shelter were slowly coming together, with a 250-bed facility planned at the time, but until there was somewhere for the campers, WSDOT refused to remove the camp.

“It will be done in the most humane way possible, when we know they have a place to go,” WSDOT regional administrator Mike Gribner said.

On the surface, things moved more quietly in the spring, as city officials and politicians worked to open a shelter of some kind.

By the end of April 2022, the Woodward administration had identified that the city’s new homeless shelter would be located in a trucking warehouse on Trent Avenue owned by Larry Stone, a local developer and major contributor to local conservative political action committees and politicians, including Woodward’s 2019 (and now 2023) campaign.

With 250 beds planned, the facility was slated to be the largest in the city.

The plan proved to be unpopular with the City Council’s left-leaning majority, which had recommended capping shelter capacity at around 100, and also called for both pallet shelter and drive-in models of housing, also capped at 100 people each. Woodward and conservative allies on the council expressed some interest in the concept of pallet shelters, but argued that following the recommendations would hamstring the city as it worked to get people indoors.

At the time, Councilman Zack Zappone said the limits recommended by the resolution recognized that warehousing 250 people together could create its own problems.

“We hear a lot from people in the homeless community who have that lived experience who say, ‘I don’t want to go to a warehouse. I don’t want to be there,’ ” he said.

Asked about those preferences, Woodward said, “I think we need to get to the point where we’re working to make homelessness less comfortable and get people connected to services.”

Just as summer began, a lease for the new shelter was approved begrudgingly by the City Council.

The council’s earlier recommendations ignored, the left-leaning majority insisted that the city should purchase the Trent Avenue warehouse before investing millions into renovating it. The Woodward administration refused, arguing that it was unwise to spend $4 million purchasing a facility when it was unclear how long it would be needed, and instead negotiated a $1.6 million 5-year lease. Negotiators included a nonbinding option-to-purchase clause in the lease agreement which would prove meaningless after the City Council exercised it a year later, when Stone would reportedly ask for over $8 million, double the property’s assessed value.

Around this time, the state Department of Commerce offered around $24.3 million in state funds to help relocate people out of Camp Hope and into “meaningfully better” conditions, part of the program authorized by the state Legislature to clear encampments.

On July 4, a second person was found dead in a tent at Camp Hope. The population had doubled since March, with upward of 600 people calling the tent city home, the largest anywhere in the state.

“This camp is growing faster than we can do anything about, mostly because they’re clearing out people from downtown, and everybody just comes here,” Garcia said at the time.

Despite growing larger than the total population of dozens of rural Washington towns, the space did not have access to city services, and had insufficient portable toilets and no hand-washing stations. All but three people staying there reported having no form of ID. After campers reported being pelted by paintballs, pellet guns and bear spray, trailers were placed as a makeshift wall between the camp and I-90.

Meanwhile, the mayor and City Council clashed over anti-homeless laws for city-owned property, including where and when homeless people could be cited for camping, sitting or lying.

“I think the mayor would be happy if she could remove anybody camping anywhere, but that’s not what the law is right now,” Council President Breean Beggs said at the time. “So the question is how far can we go under the law and how much risk do you take on having all our laws struck down and being sued for money?”

A survey of 601 Camp Hope residents released in July showed unanimous support for pallet shelters or tiny homes, while only 8% said they would go into a congregate shelter like the one being created on Trent Avenue – and even that 8% depended on which operator was managing the facility.

In the soaring July heat, Heather Morse said that her tent felt like an oven every day after 8 a.m. Still, she stated unequivocally that she would never go into a shelter.

“If that’s what happens, that’s what happens. I would never go to it,” Morse said at the time. “I would still be out here or wherever else I could be.

Around this time, the city sent its proposal for how the $24.3 million slated to help clear Camp Hope should be spent. The proposal, signed by Woodward, Beggs, Zappone and Councilwoman Lori Kinnear, included a $6.5 million line item to purchase and rehabilitate a former Quality Inn on Sunset Highway to convert it into affordable housing units for around 100 people. This would eventually become the Catalyst Project, operated by Catholic Charities.

Funding proposals for the Trent shelter suggest that the facility would operate with a capacity of 60 two-person “pods,” as administration officials acknowledge a lack of privacy may cause some to avoid coming to the shelter.

Temperatures would soon top 100 degrees. With a shelter still months away, volunteers erected a Quonset-style tent at Camp Hope to act as a cooling shelter. Like the camp itself, WSDOT does not sanction the tent’s construction but looks the other way.

Within days, Spokane Fire Department Fire Marshal Lance Dahl sent a letter to WSDOT demanding the “illegally constructed” tent be removed if the agency doesn’t take responsibility for it and acquire permits. WSDOT officials refused. By the beginning of August, City Council members, many of whom voiced support for the structure, would earmark funds to support the cooling tent’s operations.

Neighboring residents and business owners complain of a spike in crime around Camp Hope. Cameron-Reilly LLC, a contractor hired to complete reconstruction of Thor and Freya streets, claimed the camp had led to vandalism and theft, and would receive a $70,000 settlement from the city.

Meanwhile, Jewels Helping Hands complained that, despite near-constant law enforcement presence near the camp during the day, they are unable to receive assistance from police to remove troublemakers from the camp. These complaints would persist.

The Spokane Police Department launched drones to surveil the camp, and reported one was taken out of the air by a homeless person piloting a drone of their own.

The state contracted with Empire Health Foundation in early August to coordinate services at Camp Hope, including those provided by Jewels and Compassionate Addiction Treatment.

Neighbors protested plans to convert The Quality Inn on Sunset Highway into a homeless facility, saying they weren’t consulted before the site was chosen. Woodward, who had signed off on the plan, tells angered residents that the fault lies with the state Department of Commerce for giving the city so little time to craft proposals for state funds. Woodward tells residents to complain to then-Commerce Director Lisa Brown.

The city readied contracts with the Guardians Foundation to operate the facility. The facility opened with 75 beds on Sept. 6, and 36 people stay there the first night, 13 of whom said they came from Camp Hope.

The next day, the city resumed arresting and citing the homeless for sitting or lying on sidewalks in downtown Spokane.

Though the city did not have enough shelter for all of its homeless, the administration begins enforcement under a favorable legal interpretation of the Martin v. Boise circuit court decision, case law which limits how cities can criminalize the homeless if there isn’t shelter available but isn’t clearly defined.

Another day later, Woodward threatened legal action against the state if Camp Hope didn’t close by mid-October. In response, the state accused Woodward of valuing optics over action.

Enter former Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich. After nearly a year of being largely absent from the political brawls over Camp Hope, Knezovich declared that the sheriff’s office would assist with clearing Camp Hope if it wasn’t closed by the city’s October deadline. For months to come, the sheriff would be a regular figure in the ongoing controversy, appearing several times on Fox News to insinuate wrongdoing, and often appearing shoulder-to-shoulder with Woodward and accusing state and local officials of keeping the camp open due to politics and graft.

As tensions over crime and safety boiled over, WSDOT enacted security measures at Camp Hope, including erecting a fence and creating a badge system that keeps track of campers and prevents unregistered people from entering the lot. An 8 p.m. curfew was put in place, as well as a “good neighbor agreement,” a set of rules to mitigate the impact on neighbors.

Less than 450 people receive badges, and camp managers report the population had dropped noticeably from the peak of 623 people. Between 40 to 70 had gone to the Trent shelter, depending on reports, and city officials began to claim that the facility’s capacity was not 150, or 250, but nearly limitless, using floor mats to accommodate overflow.

“In theory, you could put everybody in there,” Coddington said on Sept. 27.

In early October, Spokane County announced its intentions to sue WSDOT over Camp Hope, hoping to get a judge to support Knezovich’s deadline for the camp, which had been pushed back to mid-November.

Woodward said she had requested the extension, wanting to stand up additional shelter for the hundreds staying at Camp Hope. Around this time, 24-year-old James Rackliff was arrested after he was accused of a drive-by shooting, firing into Camp Hope, though he caused no injuries.

As the November election approached, Camp Hope animated the campaigns for county sheriff, prosecutor, commissioners, and other races. Spokane ended its contract with the Guardians amid accusations of embezzlement, and entered into a contract with the Salvation Army.

Camp Hope residents and service providers filed suit against the city and county to block them from sweeping the camp before the residents were placed into housing. Meanwhile, state agencies worked to get Camp Hope residents ID cards.

After the mid-November deadline came and went, Woodward said it had always been aspirational, not an ultimatum. Knezovich, disbelieving the reported census at Camp Hope, authorized the use of helicopters and infrared imaging to survey the site. The county approved the use of $500,000 to replace 250 wooden beds at the Trent shelter with 350 metal beds, though city officials continued to maintain hundreds more could be sheltered at the facility in a pinch.

Temperatures plummeted. A trailer at Camp Hope caught fire, displacing two residents. At the anniversary of Camp Hope’s opening, Woodward cast blame at the state Department of Commerce for the camp’s continued existence. Spokane police and county sheriff’s deputies handed out flyers at the camp warning: “This camp is to be closed,” though no new deadline was issued.

Despite protest, the Catalyst Project opened Dec. 8. In batches, around 100 Camp Hope residents would eventually find their temporary homes there, as well as various services, including job training. A federal judge blocked efforts to sweep Camp Hope before Christmas. A Camp Hope resident was arrested with hundreds of fentanyl pills, stolen credit cards and clothing, and handguns.

Shortly before Christmas, temperatures dropped into the negative teens. Woodward pledged anyone who needed shelter from the cold would have refuge at the Trent shelter. City officials blamed a miscommunication when residents were turned away on Dec. 21.

In January, the county withdrew its lawsuit over Camp Hope in a show of good faith, hoping to allow breathing room for negotiations and coordination of the camp’s closure. By February, the population in the camp was just over 100. On the first day of March, Brown, who had clashed repeatedly with Woodward over the correct path to address Camp Hope, announced her bid to become Spokane’s mayor.

Just before the official start of spring, a propane explosion burned two people living at the tent city.

Citing the recent fires and a belief that clearing Camp Hope had not been proceeding quickly enough, the city of Spokane filed suit, asking a judge to force the state to agree to a deadline. Superior Court Judge Marla Polin agreed that the site could be considered a nuisance under the city’s municipal code, and required both parties to work on a closure plan. Both sides declared victory.

In mid-May, another fire destroyed an RV at Camp Hope. Another miscommunication is blamed as people are turned away from the Trent Shelter.

By the end of the month, city and state officials declared in a joint statement that they had come to an agreement accepted by Judge Polin: Camp Hope would be closed by June 30.

On Friday, just a day shy of the 18-month anniversary of the beginning of the Camp Hope, the last person was moved into housing, the last tents were removed, the gates were locked, and the camp was closed.

A timeline of the Camp Hope homeless camp in east Spokane.

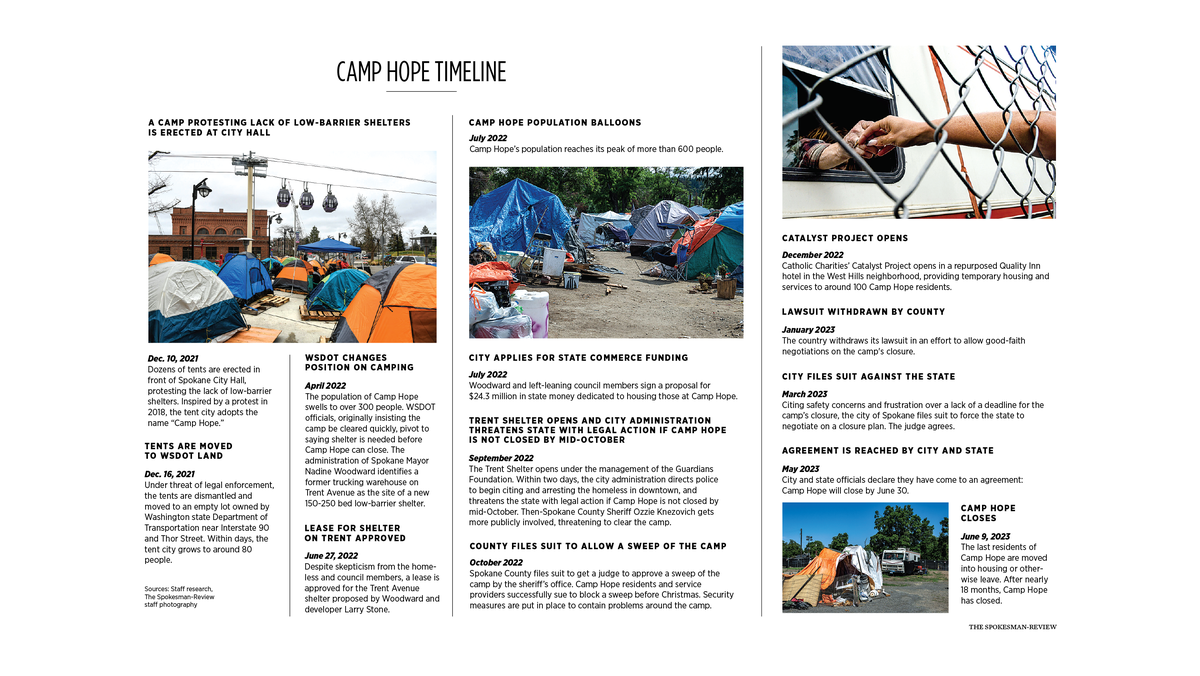

Dozens of tents are erected in front of city hall, protesting the lack of low-barrier shelters. Inspired by a protest in 2018, the tent city adopts the name "Camp Hope."

Under threat of legal enforcement, the tents are dismantled and moved to an empty lot owned by WSDOT near I-90 and Thor Street. Within days, the tent city grows to around 80 people.

The population of Camp Hope has swelled to over 300 people. WSDOT officials, who had originally insisted the camp must be cleared quickly, pivot to saying shelter is needed before Camp Hope can close. The Woodward administration identifies a former trucking warehouse on Trent Avenue as the site of a new 150-250 bed low-barrier shelter.

Camp Hope's population reaches its peak of more than 600 people. A lease is signed for the Trent Avenue shelter, despite skepticism from the homeless and councilmembers. Woodward and left-leaning councilmembers sign a proposal for $24.3 million in state money dedicated to housing those at Camp Hope.

The Trent Shelter opens under the management of the Guardians Foundation. Within two days, the city administration directs police to begin citing and arresting the homeless in downtown, and threatens the state with legal action if Camp Hope is not closed by mid-October. Former Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich gets more publicly involved, threatening to clear the camp.

Spokane County files suit to get a judge to approve a sweep of the camp by the sheriff's office. Camp Hope residents and service providers successfully sue to block a sweep before Christmas. Security measures are put in place to contain problems around the camp.

The Catalyst Project opens, providing temporary housing and services to around 100 Camp Hope residents.

The country withdraws its lawsuit in an effort to allow good-faith negotiations on the camp's closure.

Citing safety concerns and frustration over a lack of a deadline for the camp's closure, the city of Spokane files suit to force the state to negotiate on a closure plan. The judge agrees.

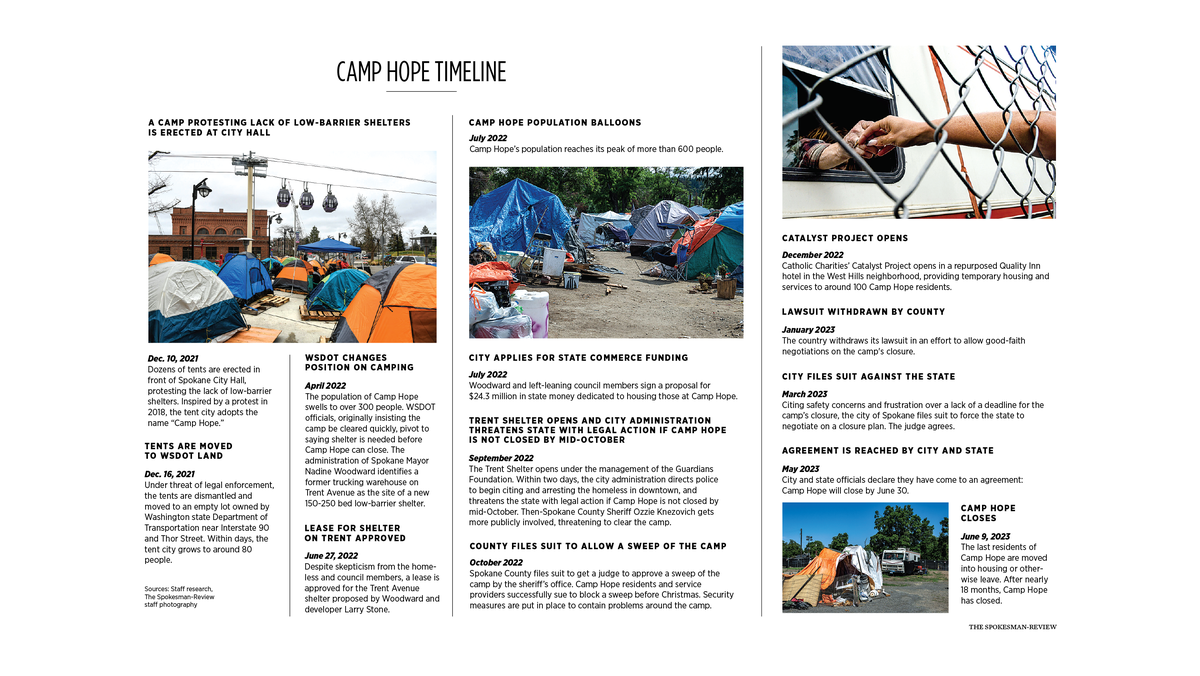

City and state officials declare they have come to an agreement: Camp Hope will close by June 30.

The last residents of Camp Hope are moved into housing or otherwise leave. After nearly 18 months, Camp Hope has closed.