Seventy-five years ago Wednesday, President Harry Truman issued a pair of executive orders involving Civil Rights for African Americans in the wake of World War II. One of those called for ending the military's policy of keeping white and African American servicemen in segregated units.

Sgt. Major Cleveland points out North Korean positions to the machine gun crew he leads near the Chongchon River in Korea in 1950.

The Awakening of Harry Truman

On Feb. 12, 1946, 23-year-old Isaac Woodard Jr. was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army after serving in the South Pacific during the Second World War. He was mustered out at Fort Gordon in Augusta, Georgia, and caught a Greyhound bus to his home in Winnsboro, South Carolina, when he drew the ire of the bus driver for asking if he could use the restroom at a rest stop near Aiken, South Carolina.

The bus driver reported him to the police chief in the next town. The police removed Woodard from the bus, arrested him and beat him repeatedly, gouging out his eyes. He wasn't permitted medical treatment for two days.

“My God,” exclaimed President Harry Truman when he read about the incident in newspapers. “I had no idea it was as terrible as that. We've got to do something!”

And that's how a Missouri Democrat who had a family history linked to the Confederacy and no particular interest in Civil Rights became a believer.

Truman created the President's Committee on Civil Rights to look into lynchings and other atrocities that were committed throughout the South and to see what could be done to cut down on racial violence and to begin equalizing Civil Rights.

His committee released its report in October 1947. The next February, Truman invited the wrath of his own party — especially Southern Democrats, an in an election year — by setting into motion a number of its recommendations.

Among them was banning the military's policy of keeping Black and white servicemen segregated during the two world wars. African Americans had fought with distinction in both conflicts but had been treated poorly and given sub par equipment and housing by their own leaders. That had to end.

With Southern Democrats exiting the party to form essentially a third party — folks called them “Dixiecrats” — Truman issued two Executive Orders on July 26, 1948. One, Order 9980, forbade racial discrimination in the federal civil service. The other, Order 9981, provided for “equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.”

Among those offended by Executive Order 9980 was World War II hero and Army Chief of Staff Gen. Omar Bradley. “The Army is not out to make any social reforms,” Bradley told the Washington Post. “It will change that policy when the nation as a whole changes it.”

Bradley reversed course shortly after and apologized to Truman. Still, it would take years for the military to make the changes. The final segregated regiment wasn't disbanded until 1954.

African Americans in the Military

World War I

Only about 11% of Army personnel in World War I were African Americans. Black men were often turned away from recruiting stations because there were only so many Black regiments to place them into.

While up to 30% of the Navy's manpower in the late 19th century had been African Americans, this was sharply curtailed in the early 1900s. Most African Americans in the Navy in World War I were limited to working in the galley or in the coal room.

World War II

Roughly 1.5% of Army and Navy personnel in June 1940 were African Americans. Virtually none served in the Marines or the Army Air Corps. Many African American veterans faced racism upon their return home.

Vietnam War

African Americans made up 16.3% of all those drafted in 1967 and 25% of the military personnel sent to Vietnam — and 25% of casualties there. Meanwhile, African Americans made up only 11% of the U.S. population at the time.

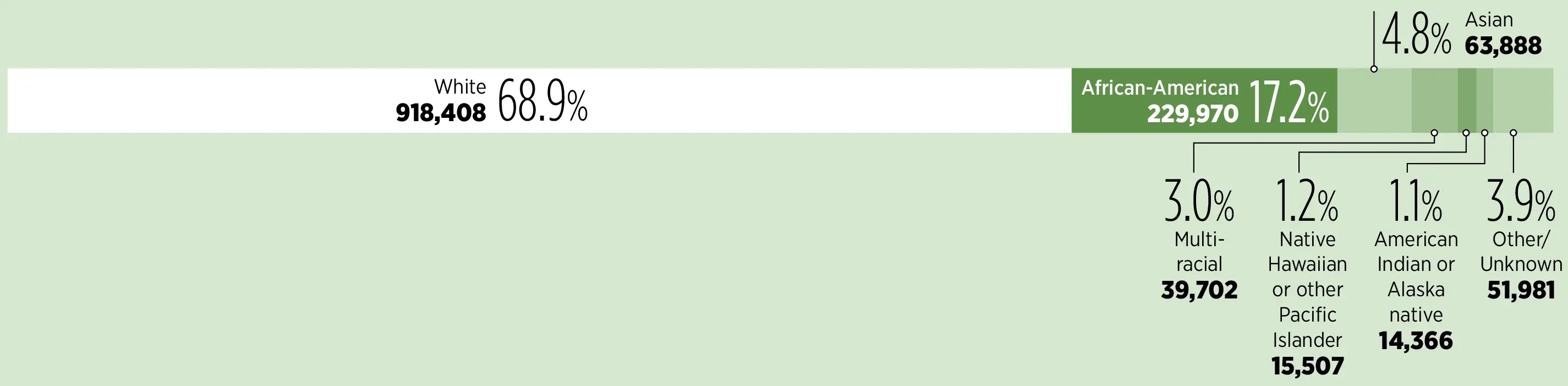

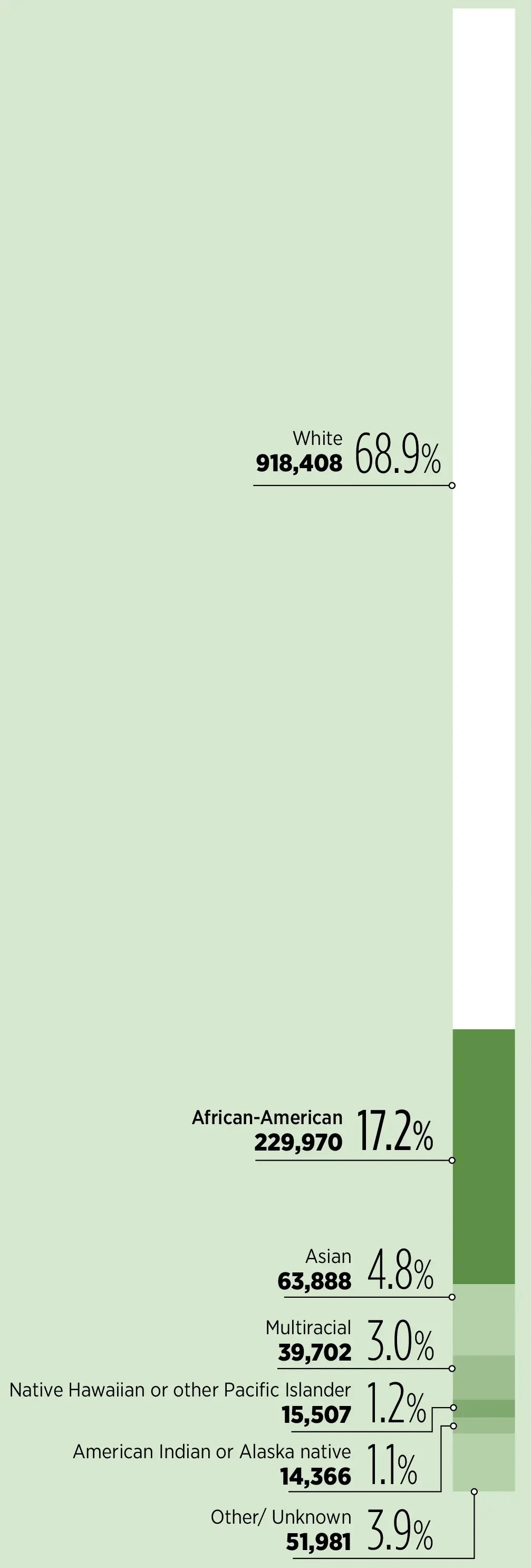

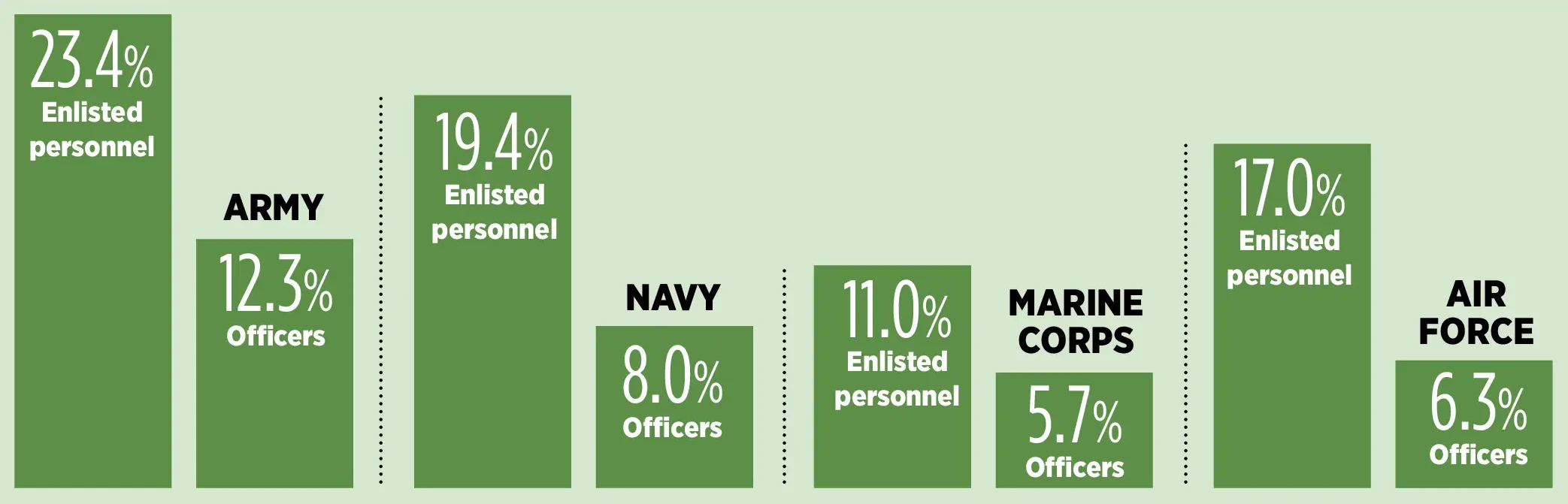

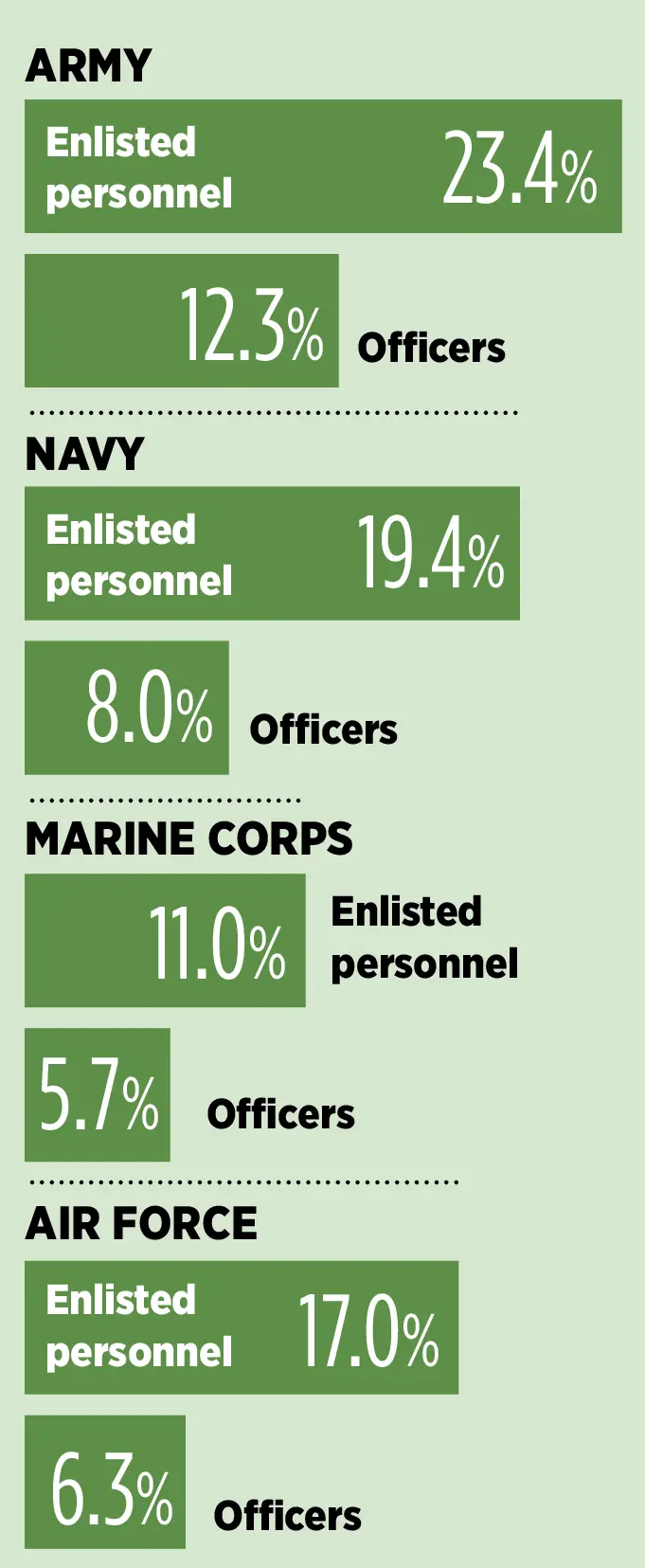

Demographic of the U.S. Military Today

These numbers date from September 2000, when there were 1.3 million Americans serving in the military

The Percentage Who Are African-American

This edition of Further Review was adapted for the web by Zak Curley.