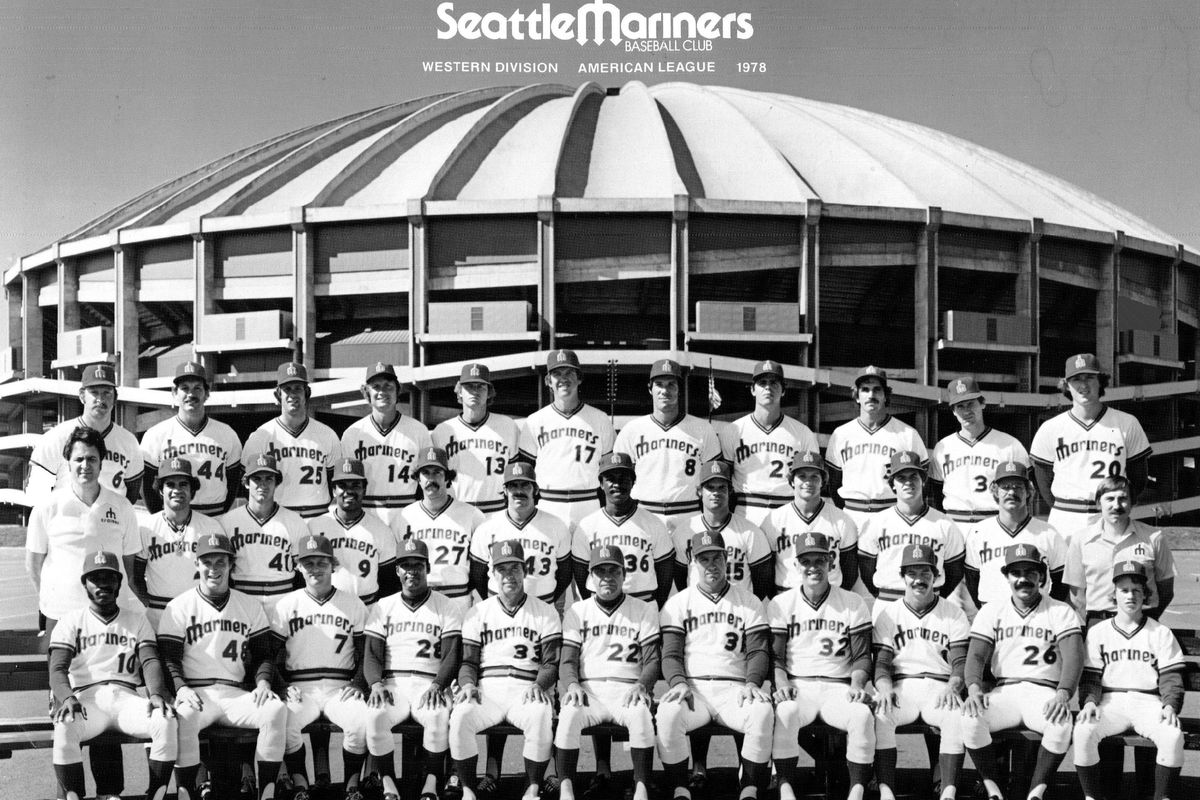

Commentary: 1979 Mariners All-Star Bruce Bochte’s life after baseball? It’s complicated.

SEATTLE – Bruce Bochte isn’t one of those former MLB players who bemoans the modern game and its “look-at-me” practitioners.

Far from it. Bochte, 72, is an avid baseball watcher at his Petaluma, California, home. He is savoring the improbable contention of formerly struggling teams such as the Reds, Orioles and Diamondbacks – “and even Pittsburgh was there for a while. It’s really refreshing.”

Bochte is “elated” about the pitch clock, which he believes “is going to save the game.” And the ostentatious celebrations for home runs, strikeouts and victories that irk so many old-timers? Bochte loves it, because it reminds him of his time playing for Rene Lachemann, his Mariners manager in 1981-82 – and his favorite.

“Lach let the characters come out,” Bochte said. “He had room for people to be themselves, which they foster today. It’s good. The players are so much more expressive. Their eccentricities and oddities come out.

“I love baseball. It’s the greatest game ever to be a part of. But I diverted paths after my career.”

…

And therein lies one of the most fascinating journeys of any player in Mariners history. With the All-Star Game back in Seattle for the third time, Bochte’s name is being invoked often these days. In 1979, he was the lone Mariners representative when the city hosted the Midsummer Classic for the first time, and got a pinch-hit RBI single at the sold-out Kingdome off future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry that briefly put the American League ahead. Bochte, a left-handed first baseman and outfielder, went on to hit .316 that year, with 16 homers and 100 runs batted in.

Bochte ranks eighth on the team’s all-time career batting average list, his .290 wedged between Ken Griffey Jr. (.292) and John Olerud (.285).

The Mariners invited Bochte to be part of the festivities when the All-Star Game returned to Seattle in 2001, and again this year. But Bochte politely declined both times, simply because he realizes it would be too difficult to explain what his life has been like since he left baseball after the 1986 season.

Simply put – and it’s far from simple – Bochte has devoted his post-baseball life (and much of his life while he was playing) to studying the relationship between humans and the history of the universe.

“Environmental stuff is the easiest way to say it for me,” he said. “And it’s been fascinating and disturbing. It’s hard for me to be around people, because it’s always on my mind. And I’ve been working with it for 40 years now. It was very hard to talk about when I was playing. Occasionally, they’d probe, and I didn’t know what to say. It was just so shocking to me at that time. And so it (the All-Star Game) wouldn’t be comfortable. I don’t think I’d enjoy it, as much as it’s a fabulous event.”

…

To get the full picture you have to go back to 1982, Bochte’s fifth season in Seattle. After hitting .297 for the Mariners in 144 games, Bochte simply walked away from baseball for a year. He was 31 and in his prime – Seattle’s career leader at the time in nearly every offensive category. But a stint as the Mariners’ union rep during the 1981 players strike had dismayed him.

“I flew around more during that strike than I did when we had the regular schedule, because we had meetings in New York and Chicago and Los Angeles with the Players Association and (union head) Marvin Miller, who was one of the most stellar people I’ve ever experienced. And I just became disillusioned. I said, ‘OK, I’ve got a year left on my contract. In ’82 had a good season. And I’m going to walk away from this. I’m not going to participate anymore.’ ”

It was, Bochte explains during a lively phone interview, “an existential, philosophical kind of thing. I was very much being educated by my friend, Brian Swimme, who I’ve worked with since I got out of the game.”

Swimme, a Tacoma native who received his doctorate in mathematical cosmology from the University of Oregon and was on the mathematics faculty at the University of Puget Sound, is one of the most renowned philosophical thinkers in America. The two met on the freshman basketball team at the University of Santa Clara in 1968 and have been kindred spirits in contemplating weighty topics like ecology, the environment and cosmology, which is the science of the origin and development of the universe.

“We were devouring stuff,” Bochte said. “We were going to try to find out something about what was going on in the world. Neither one of us could buy it.”

…

Even while he was playing, Swimme said, Bochte would soak up all the knowledge he could.

“We discovered some spectacular teachers, so we were actually learning together,” Swimme said, chuckling at “the image of Bruce in these fancy hotels where the team would stay, and the entire room would be filled with books and notes he was taking. It was like a library. It was like he was going to graduate school on the road.”

Bochte was concerned with matters that don’t usually come up in a baseball clubhouse. His teammate and good friend with the Mariners from 1978-81, outfielder Tom Paciorek, said Friday, “I always felt like Bruce was smarter than the rest of us. And I think pondering things was really a key for him. He waited before he spoke. He was really an intellectual guy. He was always a step ahead of us, and he could make us all look really dumb. So we kind of stayed away from conversations with him about anything other than baseball.”

Not Dusty Baker, a deep thinker in his own right who was Bochte’s teammate on the 1986 Oakland A’s after Bochte returned to baseball. He would happily engage Bochte on esoteric matters.

“I love Bruce,” Baker told the Seattle Times’ Ryan Divish on Friday in Houston before managing the World Series-champion Astros against the Mariners, his face lighting up at the mention of Bochte’s name. “Bruce and I used to talk about philosophy and a lot of things. … Bruce was the one that explained to me about the Western shelf and the earthquakes.

“We were really just talking about the world. We’ve talked about horticulture, gardening, just world peace. We talked about water and global warming – we talked about that back then. I really like talking to Bruce Bochte – and he was a heck of a player, too.”

Paciorek – who had an 18-year career before going into broadcasting – said Bochte and Frank Thomas were the two best breaking-ball hitters he saw. But Bochte, an anchor of the Mariners lineup, left the game behind after the 1982 season for what he called “a year of exploration.”

…

He took classes at the University of Washington. He embarked on expeditions to what he calls “alternative places” to gather more knowledge. That included the Chinook Learning Community on Whidbey Island, where he and Swimme immersed themselves in conferences and speakers.

“We had fun with it,” Swimme said. “It was a great time to explore this whole idea of deep ecology, just the planet Earth and its future. That’s when we really dove into it deeply.”

“My bent was the ecological one, the environmental one,” Bochte said. “I wanted us to get green – and that was the ’80s.”

Asked if we’re any closer to that goal some 40 years later, Bochte said ruefully, “Not much. Just a tad. I mean, there is a myriad of new ideas, technologies, possible solutions. We already have the knowledge and the tools. But they need to develop and grow exponentially. Starting now! We have to make these gargantuan leaps. … So that’s what I’ve been doing – following the ecology, the ecosystems, the climate, the oceans, the species.”

Bochte returned to baseball with Oakland in 1984, surprised by the number of teams that pursued him during his sabbatical. After a lackluster season in 1986 (“I had five good years and five mediocre ones,” he said, summarizing his career), and worn down by all the losing (Bochte never played on an MLB team above .500), his career was over.

This time, his departure was not entirely voluntarily. MLB was entering what Bochte terms “the first year of the conspiracy” – collusion against free agents for which the owners were eventually saddled with a $300 million penalty by an arbitrator in 1990. Bochte’s share helped pay for a new house in Mill Valley, California, for him and his second wife, Pamela, right over the Golden Gate Bridge near Sausalito.

But even if he hadn’t been frozen out by collusion, Bochte was likely headed for retirement at age 35 anyway – for good this time, a .282 career hitter in over 1,500 games but burned out on baseball.

“I was just out of energy,” he said.

…

What reinvigorated Bochte was diving deeper into his exploration of the natural world. Bochte has lived a rich, eclectic life. That includes working on the board of the Adopt-A-Stream organization in Snohomish County, helping to restore the salmon in Maxwelton Creek on Whidbey Island and becoming heavily involved with the protection and restoration of the San Francisco Bay. His wife was an executive for seven years with the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, helping to build a renowned seal hospital.

But the bulk of Bochte’s time has been spent with Swimme at the California Institute of Integral Studies, particularly with its research affiliate, the Center for the Story of the Universe, designing educational programs to study the relationship between humans and the history of the universe.

The goal, he said, is to tell “the whole story from the beginning of time as we know it, from modern science, contemporary science, until now, as a way of getting people to know the natural world or connect with the natural world.

“There’s a layer that’s missing out of our brains right now. And it’s not in our educational systems. I am just shocked that we won’t take a better look at this situation. Because we’re on the verge of dire.”

Swimme, working for an organization called Human Energy, becomes animated when talking about its focus on the noosphere, which he describes as “the way in which humanity is creating a kind of nervous system for the planet as a whole.”

But Swimme acknowledges that the way he and Bochte look at the world – how it’s threatened, and how it could be saved – is not prevalent.

“There’s maybe one-tenth of 1% of humanity that’s thinking this way. That’s a lot of people distributed around the planet. But it is discouraging. Bruce got very discouraged, because he would try to explain the situation to people, and it’s very threatening. I mean, it’s going to be a very different society. And so naturally people are resistant to take in, and the magnitude of the change required. So Bruce has felt distance from people.

“Bruce is like a lot of baseball players that are brilliant in a kinesthetic sense of really having deep knowledge about the dynamics of play. But in addition to that, Bruce had developed a very profound view of the nature of the universe, the nature of planet Earth. And that’s exceedingly unusual among baseball players. But it’s also exceedingly unusual among lawyers and doctors and among just about anyone. We all work so hard to survive the struggle, and few people have time to really think it through. Bruce just made time.”

And he still does in retirement, as he tends to his acre garden, revels in visiting his two daughters and two grandchildren and spends quality time at nearby Point Reyes National Seashore.

…

When prompted, Bochte also thinks back, fondly, to his days with the Mariners, remembering teammates such as Paciorek, Willie Horton, Julio Cruz, Ruppert Jones, Richie Zisk and Bobby Valentine.

He lights up as he recalls a winning, upper-deck home run in 1979 off Angels All-Star Mark Clear at the Kingdome.

“I always thought they should have put little plaques up there on that third level for the guys that got up there,” he said.

He brushes off the notion that he and Paciorek were the originators of the term “the Mendoza Line” – a theory put forth by former Mariner Mario Mendoza himself.

“I love Mario, and I don’t want to have a thing with him,” he said, before postulating that he and Paciorek did possibly coin the baseball expression “emergency swing.”

“We could have picked it up from someone else,” he said. “That’s how it works. But we sure used the term a lot in ’79. And they still use it today.”

The 1979 All-Star Game, of course, “was the pinnacle of my baseball experience,” Bochte said.

“The moment that got me the most was just walking into the clubhouse that afternoon and looking around and saying, ‘Wow, that’s a pretty good club right here.’ It stunned me. There’s (Carl) Yastrzemski and Rod Carew and Don Baylor and George Brett and Jim Rice and Fred Lynn and Nolan Ryan and Ron Guidry. You go, ‘Wow, you can’t go wrong here.’ ”

And, of course, Bochte still does a lot of deep thinking about the state of things – which he acknowledges can be termed dismal.

“You’ve got to balance that with the joy and the wonder and celebration of the natural world,” he said. “It’s just the most incredible story to go through.”