Nancy Maupin credits early Alzheimer’s diagnosis, treatment for George’s ‘good seven-year run’

Nancy Maupin lost her husband, George, to Alzheimer’s on Feb. 14. (DAN PELLE/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

Only those close to George Maupin knew that the beloved Spokane TV weatherman faced a personal storm of Alzheimer’s disease soon after he retired in 2012.

Today, Nancy Maupin credits her husband’s early diagnosis and taking drugs aimed at easing the disease’s symptoms for giving him what she said were seven good years. They traveled. He enjoyed his love for books and wine.

Maupin had endeared himself to local residents with his folksy style during 12 years on the KHQ morning news show, where he coined an on-air phrase, “Spokomojo.” He died Feb. 14 at 79.

“Spokomojo became like his signature,” said Nancy Maupin, 70. “He just said, ‘It’s my way to say Spokane magic.’

“Anywhere we’d go, people would shout, ‘Spokomojo!’ It’s just one of those things that only local TV news could generate.”

The station is owned by Cowles Co., which also owns the company that publishes The Spokesman-Review.

A few months ago, Maupin joined her husband’s former KHQ co-worker, Shelly Monahan, and Monahan’s husband, Steve Cain, to talk with local Alzheimer’s Association leaders about fundraising in George’s name.

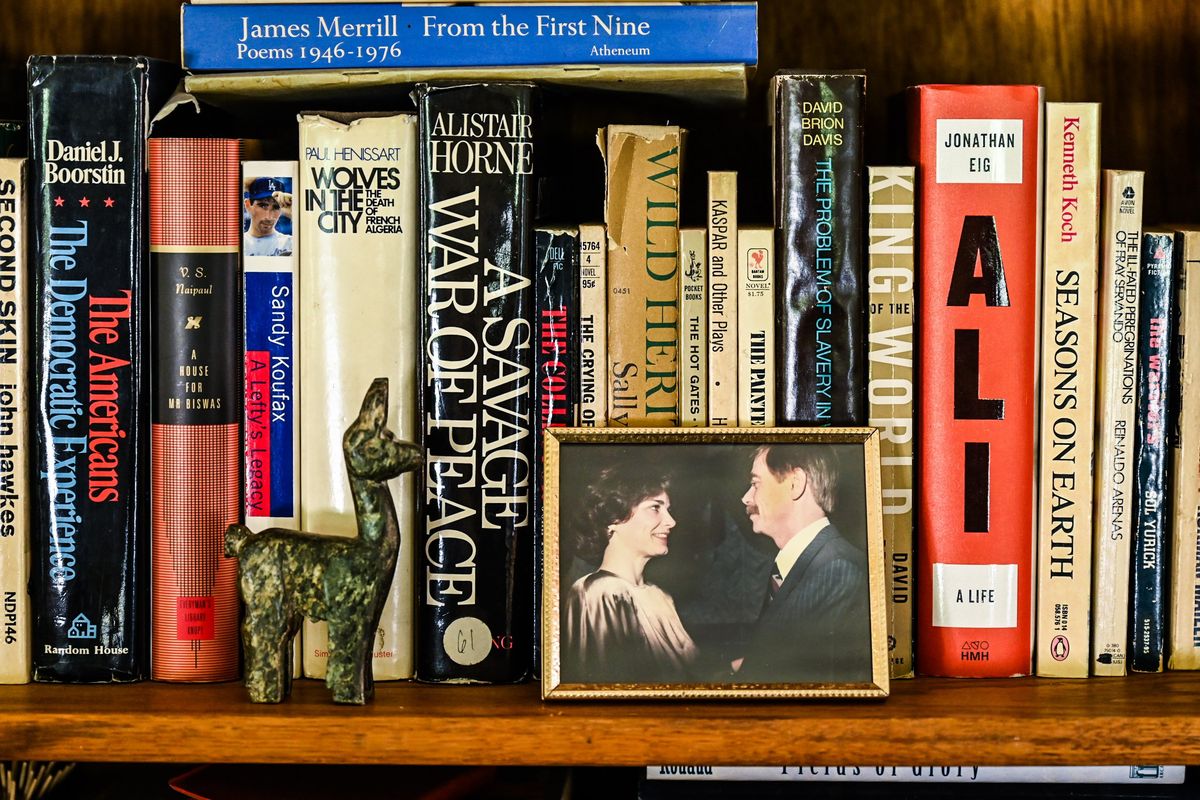

George Maupin was an avid reader, according to his wife, Nancy. Here, they are pictured on their wedding day when they eloped. (DAN PELLE/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

George would back such support for the association’s work, Maupin said. She and their friends have formed Team Maupin Mojo to fundraise for the Sept. 30 Walk to End Alzheimer’s in Riverfront Park.

Maupin, who sells Medicare insurance, said she often suggests that seniors get a yearly cognitive assessment – free under Part B coverage – for early detection of Alzheimer’s, the most common type of dementia. Age is the greatest known risk factor for the disease, typically found in those 65 and older. About 6 million Americans have the progressive disease.

Under a Veterans Administration neurologist’s care, her husband took Aricept and Memantine, drugs that Maupin said made a difference.

“He was prescribed those, and he had a good seven-year run,” she said.

He then had a stroke in early 2020, followed by a slow decline. For years prior, people couldn’t tell he had the disease if they saw him, she said.

“During that seven years, he was clicking through his bucket list.” Trips took them to Iceland, England, Scotland and France.

“We got to visit what we think was his mother’s ancestral home; we’re not really sure. He loved Shakespeare and the romance writers,” so they visited Stratford, the Lake District and poet William Wordsworth landmarks.

In France, she drove them down the Normandy coast. He saw the abbey Mont Saint-Michel, a bucket-list topper. They did a wine tour and went to the Historic town Saint-Émilion.

“He had a wonderful time, then we ended up in Barcelona, which is fabulous,” she said. Another trip was planned to southern Spain and Morocco, “but things got too bad.”

The couple met at a Las Vegas TV station after she started as a producer. He was a well-known sports anchor in the glory days of World Championship Boxing and Runnin’ Rebels basketball at UNLV.

He was 50 when they moved to Spokane with their toddler son, Will, in 1994. Behind the scenes and a producer, he offered to fill in for broadcasts. It wasn’t until a staff pinch that he took on weather.

He was a hit.

After George retired, they were headed to Ohio when he fainted on an airplane, then quickly recovered. That spurred Spokane medical checks, which diagnosed vasovagal fainting, but it also found pre-Alzheimer’s.

“Because of his age, they ran the basic cognitive assessment,” Maupin said.

The test seemed easy – naming animals alphabetically by letters, listing U.S. presidents from current back and drawing a clock face with a time.

“But they give you something when you first walk in the door, to remember these five words. You’re sitting there, ‘OK I can remember that,’ and guess what? Most people my age don’t remember those words.

“We came back six months later, did a more in-depth cognitive test, and that’s when they determined that, yes, he did have Alzheimer’s.”

Maupin said she sometimes wonders if his early risings had an impact. Impaired sleep has been associated with Alzheimer’s disease, the National Institutes of Health says. Studies suggest that sleep deprivation may increase the risk for beta-amyloid buildup in the brain.

“He woke up at 2 o’clock in the morning for 12 years to do the morning show, and we had a kid at home at the time. He didn’t always get a nap, didn’t always get a full eight hours. We don’t know. He does have a family history – his half-sister and half-brother both had it.”

There are recent Alzheimer’s gains. A new drug, Leqembi, got the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s traditional approval July 6 for patients with early Alzheimer’s disease. The treatment targets amyloid beta, the primary component of amyloid plaques, which are a disease-defining hallmark in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

Leqembi and two other new drugs, Aduhelm and Donanemab, show promise in slowing mental decline. There can be side effects. Recent news also described that the clinical trial-stage drug Donanemab, given once monthly intravenously, had promising results.

These newer drugs differ from past ones, said Erica Farrell, a state Alzheimer’s Association clinical manager.

“Aricept and Memantine – and others that have been available – those are actually treating symptoms, so they’re not actually treating the underlying disease progression. But for some people, they help to have clearer days, to function more typically,” Farrell said. “Not everybody would have those positive effects.

“These newer drugs are drugs that are actually treating the disease itself, so the underlying disease progression is being slowed.”

Maupin said she hopes people ask about options. She’s had friends get cognitive assessments after talking to her, but some clients won’t.

“I have clients who say, ‘I will never have that,’ ” Maupin said. “They’re afraid they’ll lose their driving privileges or their car insurance will go up, which it won’t.

“To me, having witnessed it for 10 years, get the assessment early and if you need the medications, take them. Worry about these other minor details down the line, because if you have Alzheimer’s and you don’t have it treated and it progresses very fast, you’re going to lose your driving privileges anyway.”

George eventually lost that privilege after an assessment found he wasn’t safe to drive, she said.

There were other tough times, like when he couldn’t get through his last book, “Philip Roth,” a 2021 biography about the novelist. Each Sunday, they got donuts and the New York Times so he could read the book review and travel sections.

“We have rooms full of books, and he loved to read. He lost that ability. He knew he lost that, and that’s the one thing that bothered him.”

Maupin said they were fortunate to have the VA and other resources, but she’s learned more lately about Alzheimer’s Association services.

“I think I will be playing a larger role with the association, lending George’s name,” she said. “It’s something he’d do. It’s obviously going to take a huge amount of resources, not just to get the disease to a cure, but to a manageable point.”