Dave Boling: After ‘Dan vs. Dave’, Olympian Dan O’Brien learned from failure and earned more than golden redemption

The admonition has reached common use: People shouldn’t allow their failures to define them. It could be titled the Dan O’Brien Doctrine.

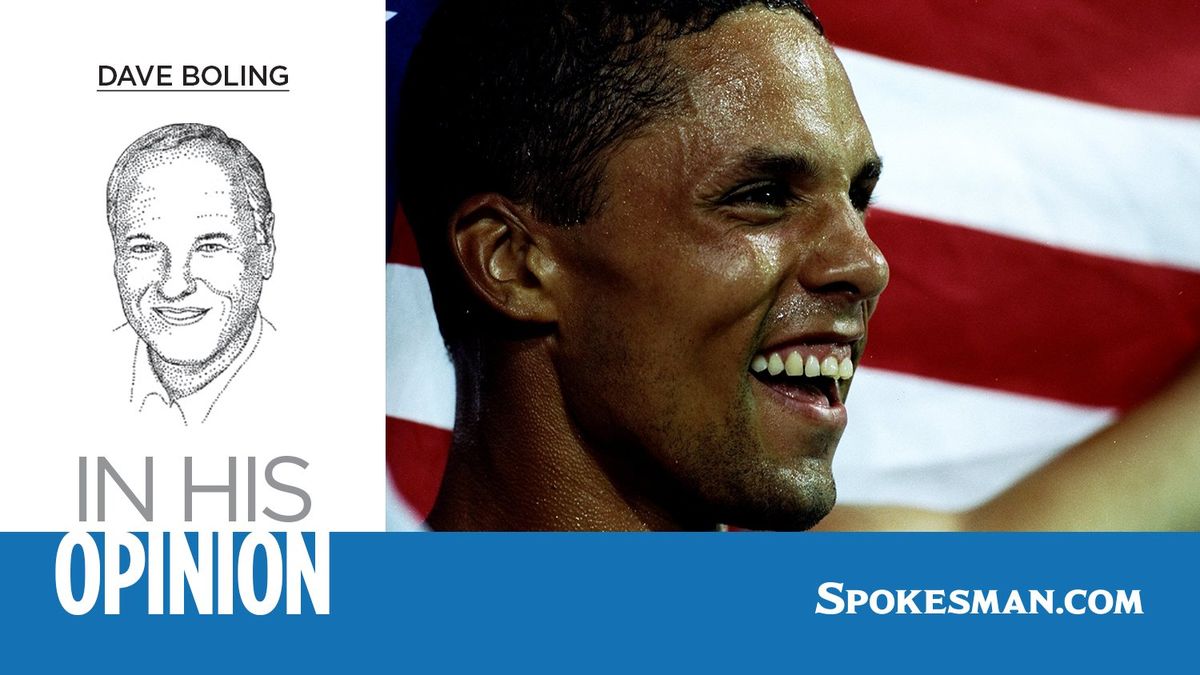

Mention O’Brien’s name to sports fans, and they will immediately recall one of two events: 1) His 1992 failure to qualify for the Barcelona Olympics decathlon with a no-height in the pole vault during the U.S. Olympic Trials. 2) His redemptive 1996 gold medal in the Atlanta Olympics.

Whichever you choose could reveal your world-view, like sports’ half-full/half-empty perspective.

“It was one of the biggest screw-ups in sports history,” said O’Brien, who will turn 57 this week. “It was also the greatest learning moment I had in my entire, my entire life. All the changes I made were based on that failure.”

For O’Brien, living in Scottsdale, Arizona, life now is definitely more than half full.

He currently works as a television analyst of major track and field meets, is executive VP of athletic performance for Legacy Sports USA, a board member of the U.S. Air Force’s World Class Athlete’s Program and a motivational speaker.

His greatest pride? “I’ve been married (to Leilani) for 20 years,” he said. “Other than that, I think the thing I’m most proud of is overcoming the failure in ’92 and fighting back to win in ’96.”

Much of O’Brien’s story is well known and oft told, except for that period of greatest self-revelation, the behind-the-scenes path from his 1992 failure to the top position on the medals podium in Atlanta four years later.

O’Brien got the medal, but it was a collaborative effort, a victory of body and mind.

…

A huge part of Dan O’Brien’s story is based on the extraordinary gifts he was given, and those that he was denied.

He was born with unique structural levers and cogs and sinewy connections that made him preternaturally strong and fast and coordinated. These gifts were the result of unknown genetic contributions, witnessed by a number of blank spaces on his birth certificate, and his initial two years of life spent at an orphanage.

“I talk to people about overcoming adversity because, hey, I had to do that from the start,” he said. “Some of the personality traits I had over the years may be from being adopted, it was difficult for me to ever say ‘no’ to anybody.”

He was adopted into a family of fellow orphans of varied race and ethnicity. His physical gifts showed up in high school to the extent they caused Idaho track coach Mike Keller to travel to Klamath Falls, Oregon, with a full-ride scholarship and the promise to look after him.

The story of O’Brien’s immaturity and irresponsibility has been detailed widely, his athletic potential going untapped as he flunked out, was diverted by alcohol and drugs, and spent time in jail for writing bad checks. Keller got him a last chance at Spokane CC, where O’Brien finally gained eligibility and returned to compete one season for Idaho.

Keller soon invited Rick Sloan, head coach at Washington State, to help O’Brien continue competing. While Keller had been the dutiful caretaker of O’Brien’s well-being for years, Sloan set a serious tone from the first day he worked with him and helped hone his field-event techniques, especially the pole vault. The three became “Team O’Brien,” and success soon followed.

O’Brien won his first of three world championships in 1991 in Tokyo, landing him a national ad campaign for Reebok, featuring the famed and doomed commercials “Dan vs. Dave: To Be Decided in Barcelona.” It brought financial relief and global attention, as well as inconceivable pressure and intense scrutiny.

…

O’Brien’s last attempt at his opening height of 15-9 in the ’92 US Olympic Trials in New Orleans was an epic failure to launch. His face a mask of confusion and fear, O’Brien almost straddled the pole in mid-air, looking more like a kid trying to shinny up a drain pipe than the world’s greatest athlete.

“You learn that you can fall to earth really quickly,” O’Brien said in the perfect analogy.

Critics wondered why he hadn’t started at a lower height, although this had been his customary opening height, and he had made 16-1 with ease warming up.

“They may have a valid point,” Sloan said. But it had been working without fail in practice and changing at the Trials would have been disruptive. Sloan pointed out that Dave Johnson, Dan’s commercial collaborator, also missed his first try at 15-9 and ended up getting past it and winning the decathlon.

Heat and humidity, the long wait to vault after warmups and a different style of landing pit could have thrown him off, Sloan said. But after that first miss, O’Brien’s technical problems were obviously intensified by the pressure.

Fair, then, to question the wisdom of Reebok to take a small-town kid, sheltered in many ways, at times with wobbly self-confidence, and make him the shared centerpiece of a $25 million global ad campaign. And then put him on the high end of a bendy stick in a superheated competitive crucible.

Keller remembers how confused O’Brien was when he approached his coaches in the aftermath. “I’ll never forget what he said, ‘Coach, can you fix this?’ ” Keller said he went out behind the stadium and “… came real near to bawling, we were devastated.”

Having bought tickets to Barcelona in anticipation, the three headed to Spain, and after doing commentary for television, O’Brien came to his coaches and told them he was back on his feet and ready to resume training. They found a small track outside Barcelona and began working with eyes on the Decastar meet in September in Talence, France.

Re-engaged, O’Brien responded with a world-record total of 8,891 points. He pole vaulted 5 meters (16-4). His world record stood for seven years, and his American record lasted 20.

“There’s not many people who could come back like that,” Keller said. “But he was such a natural. He was made for that event.”

…

His partnership with Keller and Sloan lifted O’Brien to where he felt he was at “98 percent” of his potential, but the rest of the way was a matter of controlling his mind and emotions.

“We started working together in Stuttgart, Germany (in ’93),” said Dr. Jim Reardon, sports psychologist. “Most of my practice has been dealing with trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and that’s absolutely what (Dan) went through (in 1992).

Reardon had worked with professional athletes across a range of sports, but he claimed O’Brien was unique. “Working with Dan was the most fulfilling experience in my professional life,” Reardon said. “He’s the greatest athlete I’ve ever worked with. He is so humble and unassuming, gracious and grateful. And he was like a sponge.”

Reardon earned O’Brien’s trust as they honed the athlete’s capacity to focus and control his mental state. For three years, the psychologist never brought up the ’92 trials failure.

In the winter before the ’96 trials, though, Reardon brought O’Brien and Keller and Sloan to a meeting and showed them the video of the ’92 vault.

“Dan’s face went white; we watched it a couple times, and it was like he was mesmerized,” Reardon said. “We sat there for probably five minutes and nobody said a word. I finally asked him how he felt when he watched it. He said, ‘The truth, I felt like throwing up.’ And I told him that’s why I wanted him to experience that now instead of in June.”

The goal, Reardon explained, was to “completely desensitize him” to the pressure arising from those memories.

Reardon asked Sloan to “kind of brow-beat him a little bit,” trying to get O’Brien as anxious as he could during practices so he could acclimatize to pressure. At one point, Sloan brought a WSU photography class out to the track and got them in a circle around the pit where they would click loudly and endlessly while O’Brien jumped, knowing that the media would be following his every vault at the trials.

O’Brien felt so in control of his own competitive fate at the ’96 trials, he independently decided to come in two heights earlier than expected in the pole vault. He cleared the lower height easily – and was well into the competition before the army of photographers could gather near the pit.

He went on to win the trials and the gold medal in Atlanta. He never chose an opening height of 15-9 in the pole vault after 1992.

…

O’Brien has enjoyed coaching at times, but his favorite work now is television. “Nothing beats competing as an athlete,” he said. “And I loved coaching, helping people compete at a high level, but, yeah, I really enjoy the television part of it. As I’ve gotten older, my passion for track and field is as strong as ever; how can I contribute and what can I do to make the sport better?”

He has several different presentations he makes as a speaker, depending on the target audience. “I talk about overcoming adversity,” he said. “I share moments in my life that had the biggest impact, and the importance of setting goals and working toward them – positive self-talk, and thinking like a champion.”

O’Brien is generous in his appreciation of the patience and dedication of Keller and Sloan, and the valuable insights of Reardon. But in retrospect he also understands the importance of his own determination, and he shares that especially with groups of young athletes.

“I tell them they need to be responsible for their own failures as well as their successes.”

O’Brien has lived that advice, taking ownership of every bit of glory and disaster along the way.

“I’m as proud of him for what he’s accomplished aside from athletics as I am for what he ever did in competition,” Sloan said.

Reardon concurs.

“Considering the trajectory his life was taking at times, it’s been a real triumph,” Reardon said. “He’s done so much good in his life and I hope he’s appreciated for that.”