‘We deserve better’: Residents demand action to extend radiation exposure compensation

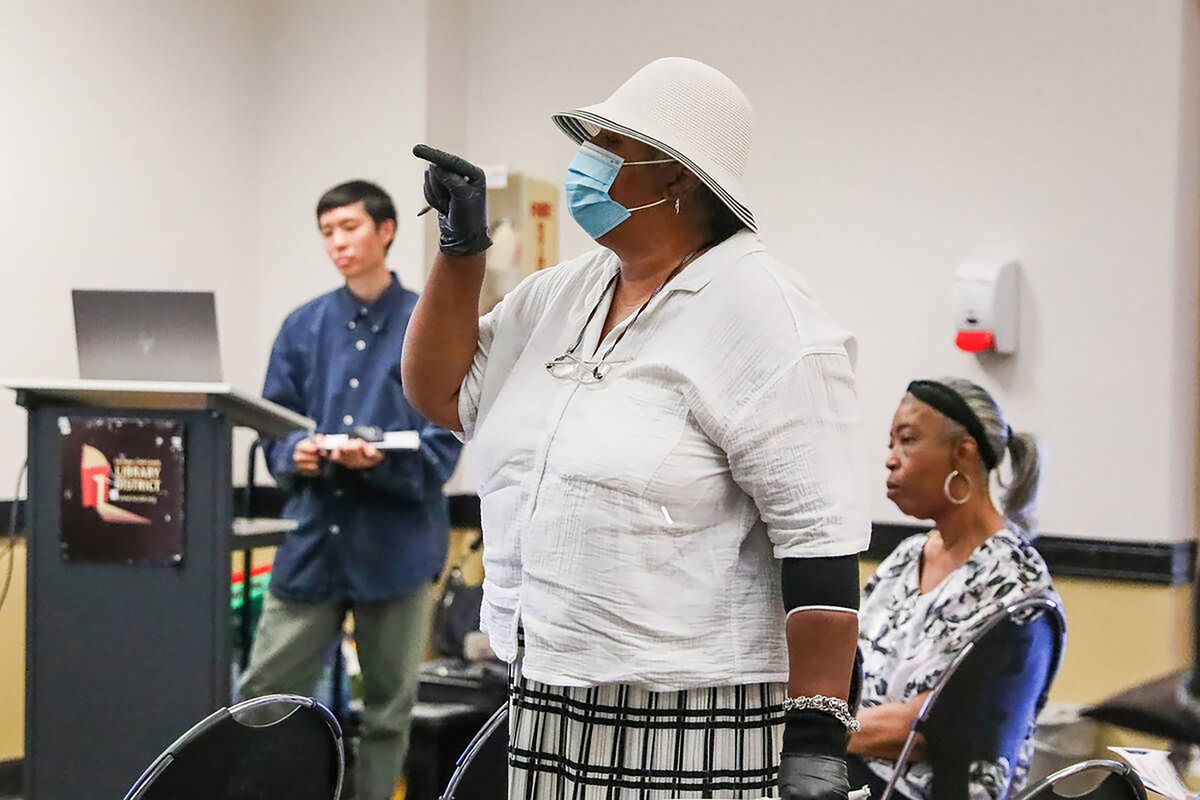

Sheron Carter calls out a representative from Nevada RESEP for misrepresenting when nuclear testing was ended in Nevada at a downwinders information session hosted by the Nevada Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program on Saturday, July 8, 2023, in Las Vegas. (Daniel Pearson/Las Vegas Review-Journal/TNS) (Daniel Pearson/Las Vegas Review-Journal/TNS)

Sheron Carter’s brother and grandfather died from cancer after working at the Nevada Test Site.

Three years ago, the 66-year-old Las Vegas native was diagnosed with breast cancer. Now, she’s demanding lawmakers take action to compensate herself and her family for the fallout from years of nuclear testing.

“It has destroyed families,” Carter said.

On Saturday afternoon, Carter was one of about 30 people who attended an information session at the West Las Vegas Library focused on a federal compensation law that is set to expire next year.

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act passed in 1990 and provides compensation to individuals and their families who lived downwind of nuclear tests, test-site participants and uranium industry workers.

Under current law, White Pine, Eureka, Lander, Lincoln, Nye and northeast portions of Clark County are considered downwind areas. Those who contracted certain diseases and lived in those areas during a specific time period can apply for compensation. Downwinders can receive $50,000, on-site participants $75,000 and uranium industry employees $100,000.

A two-year extension of the law passed last year, meaning the law is due to sunset on June 10, 2024.

Of the approximately 200 above-ground nuclear tests done in the United States, about 100 were done at the Nevada site, starting in 1951. The facility is located 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas, with the government town of Mercury at the main entrance.

Carter recalled her mother hosing down the lawn because of radiation and having to stay inside — sometimes all day — after a nuclear test.

“We have been here, we have done our diligence as citizens of Las Vegas and we deserve better,” Carter said.

Three bills proposed

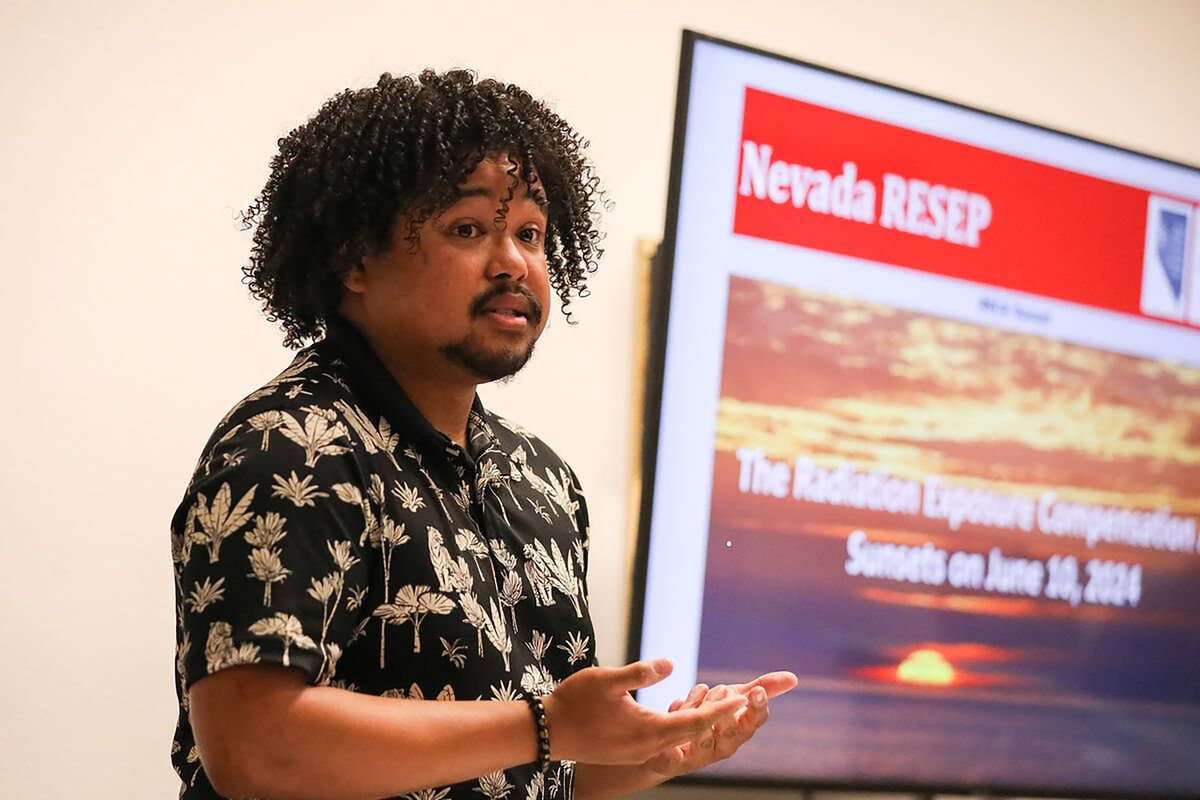

Dr. Laura Shaw, an investigator with the Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program and the Nevada Test Site Screening Program, provided updates with her team Saturday and answered questions about bills that were introduced in Congress this year.

Three bills have been introduced in 2023 to extend or amend existing law, but none have been brought before a committee.

H.R. 1751 expands downwind areas to include all parts of Clark County and Mohave County in Arizona.

It was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in March.

S. 1751 has been co-sponsored by 14 senators, including Sen. Jacky Rosen. This would extend the RECA deadline by 19 years after its enactment. It would expand the covered area to include Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Guam, as well as all of Nevada, Utah and Arizona. If passed, the bill would reduce the physical presence requirement for those exposed from two years to one year. The compensation would increase to $150,000 and provide medical benefits.

H.R. 3497 would expand the eligible time period for uranium industry workers from 1971 to 1978, and extend the RECA program for years, including for downwinders and on-site workers.

‘Fallout does not go away’

Shaw said not only would compensation end if the law expires, but the free medical screenings offered by UNLV and other grant-funded programs would end as well.

A misconception about nuclear fallout, Shaw said, is that it only impacted people in the immediate aftermath of a test.

“That fallout does not go away. That fallout spreads: People are inhaling it, increasing their risk of lung cancer,” Shaw said. “They’re drinking the milk from the cows that fed on the grass that has fallout. That fallout, 30 percent of that, is still here.”

Scott Bunn, 63, lives in Reno and attended Saturday’s event with his wife, Debra. Bunn worked on the test site between 1979 and 1983. In 2018, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma and plasmacytoma.

“We feel that it’s certainly unfair to end this program,” he said. “It should be increased if anything.”

Bunn received medical benefits and compensation through the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act, also known as EEOICPA.

Current laws allows individuals affected by radiation exposure or their families to receive money from either RECA or EEOICPA.

Bunn said it would be unfair for RECA to expire in a year because there are on-site participants who have not yet developed cancer or other diseases as a result of radiation exposure.

“It needs to be updated because when it started, 50 grand was a lot of money and it got you a long way, but now it’s not,” Bunn said.