EWU graduate who bounced around foster homes credits state assistance for defying odds, receiving degree

When Curtis Anderson was growing up, he was placed in more foster homes than he can remember or count after he was taken from his abusive family. Anderson credits the Washington Passport Network, which provides assistance to foster youth, to giving him a head start on his future despite his chaotic upbringing.

Anderson grew up in Chewelah in a family he describes as abusive, neglectful and extreme religious fundamentalists. He was put into foster care the first time around age 8, then returned to his family before being removed permanently when he was 13. But that didn’t mean he had a stable upbringing after that.

“It was pretty bad,” Anderson said. “I averaged about nine to 19 placements a year.”

He was considered a Level 1 child under a four-level assessment by state child welfare workers. A Level 4 child would have serious needs. That helped contribute to Anderson’s rapid movement through foster homes.

“It was easier to move a Level 1 because it was easier for them to adapt and then give the space to a Level 3 or 4,” Anderson said.

His constant movement made it impossible to put down roots.

“It wasn’t great for school or making friends,” Anderson said. “I basically bounced most of the time. There wasn’t much consistency.”

Things began coming together in his junior year of high school when he enrolled in Running Start, taking classes at Spokane Community College. “I knew that I wanted to go to college,” Anderson said. “I just decided to go for it.”

Running Start gave him the stability he needed. He made friends and his schooling was consistent. He met adults whom he considered to be positive role models. It was sometimes difficult to arrange his transportation to classes while being bounced from foster home to foster home, to the point that his social worker suggested that he quit.

Anderson refused. He knew a college education was his ticket out of the system.

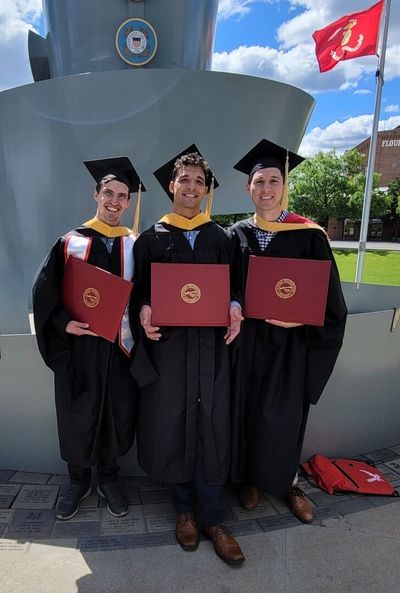

Along the way Anderson was assisted by the Washington Passport Network, which is dedicated to improving higher education outcomes for students in the foster care program as well as homeless youth. After Anderson earned his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from Eastern Washington University, he continued at EWU to earn a master’s in social work, which he received in June. Anderson worked for the Passport program as a graduate assistant while he was in graduate school.

Because he was assisted by the Passport program and later worked for it, he was able to graduate without debt. He’s currently living in Seattle looking for work. Anderson said he would like to be involved in social work in higher education or at the policy level.

“At the end of the day, it’s policy and equitable access to education that informs all things,” he said.

Anderson wants to advocate for homeless youth and youth in the foster care system so that they can also find success as adults. He said studies show that only 4 -5% of foster youth across the country are successful in earning a bachelor’s degree. “The foster system itself is not designed to help them,” he said.

Anderson was invited in May to speak at the Rise Up Passport to Careers state conference in Seattle. “I was able to speak about my lived experience and my professional experience with the system as well,” he said.

Anderson credits the Passport program and the college education he received for stabilizing his life. He said that 17 out of every 100 former foster youth become homeless in the first year after they age out of the system. Some studies also indicate that foster youth have higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder than military veterans, Anderson said.

He has no doubt that he would be among those numbers if it wasn’t for his college experience. “I’d probably be in the statistics, homeless or using drugs,” he said.

While he wants to change the system that made him struggle, Anderson is also realistic. “I can try to change the system all you want, but I’m one person,” he said. “What you really need is a community.”

Anderson urges people to call or email their state representatives to support bills that support foster youth, such as the recent Senate Bill 5230, which would have allowed extended foster care services until participants turned 25.

“It didn’t pass, but we talked about it,” he said.

People can donate to the Passport program via Washington State colleges and universities that offer the program, Anderson said. There’s also Treehouse, a nonprofit organization that supports foster youth.

“There’s so many great organizations, but they don’t run on hopes and dreams,” he said.