Meta launches parental controls for Messenger. Here’s how to use them.

Amid growing pressure from state and federal lawmakers to beef up child safety on social media, Meta is adding features that aim to protect kids from harassment, abuse and bullying.

The company said Tuesday it now allows parents in the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada to view their children’s contacts on Messenger, the messaging app shared by Facebook and Instagram. Parents can also view how much time their children spend in Messenger and whether their privacy settings allow messages from strangers. Parents will not be able to see the contents of messages.

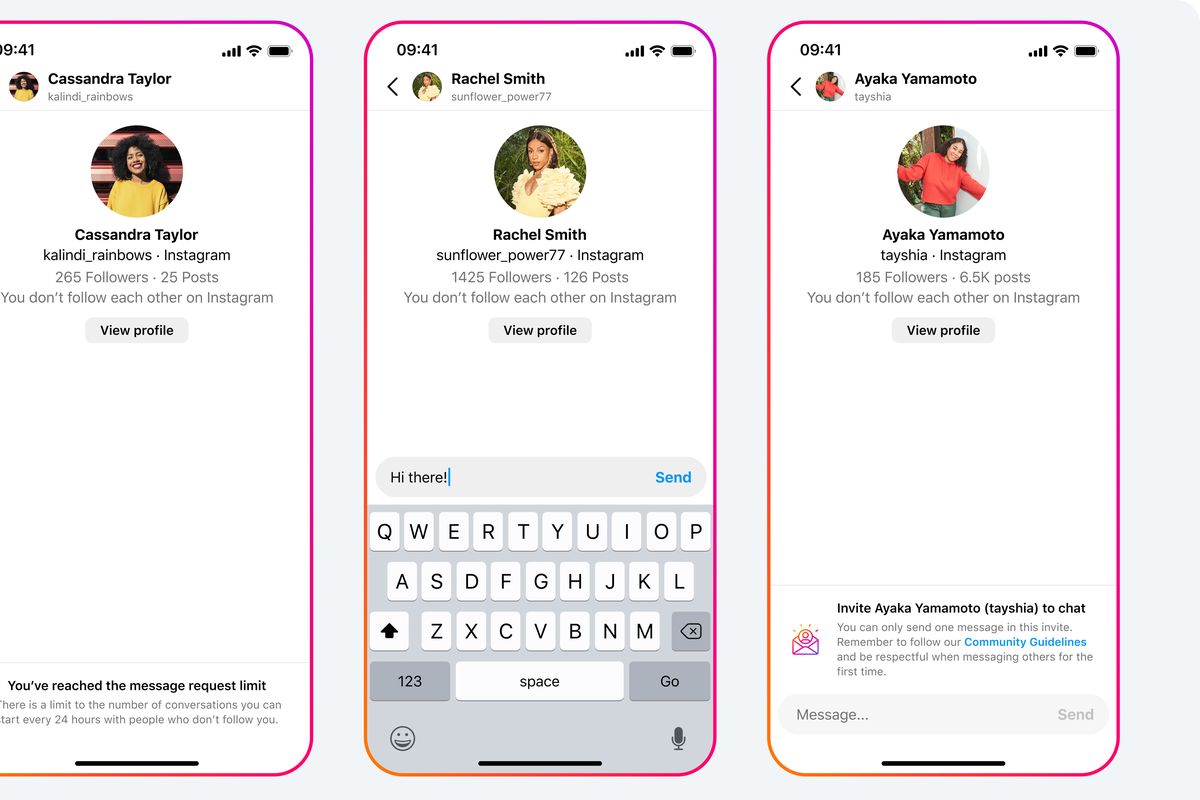

Meta is also testing a feature on Instagram that addresses harassment and predatory behavior more broadly: The feature restricts users from messaging people who don’t follow them without first sending a text-only message request.

The changes come as legislators take aim at social media companies and the health and safety risks they pose to children. Utah passed a law in March requiring teens to get parental consent before creating accounts on social media apps including Instagram and TikTok.

The attorneys general of Arkansas and Indiana sued Meta and TikTok this year for building addictive features and exposing children to inappropriate content, the lawsuits allege.

On Capitol Hill, Sens. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., and Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., are pushing for new legislation, dubbed the Kids Online Safety Act, that would require social media companies to let young users opt out of algorithmically recommended content. And last month, Sen. Edward J. Markey, D-Mass., and others reintroduced an updated children’s online privacy bill that would prohibit tech companies from collecting personal data about children under 17 and targeting them with behavior-based advertisements.

“Big tech companies have taken advantage of our children for far too long,” said Sens. Blackburn and Blumenthal in a statement to the Post. “Meta should have been working to make children safer online years ago, instead, they were too focused on monetizing their data.”

To find the new parental controls for Messenger, visit the Meta Family Center, a landing page for parents and guardians. Here, you can view your teen’s Messenger contacts and safety settings, as well as set up alerts if those settings change.

The company also said it is testing new health and safety features on Instagram, such as nudging teens to log off if they’re scrolling videos at night. Like past updates, teens can ignore these nudges and even opt out entirely of parental supervision.

Meta says its new features will roll out in more countries in coming months.

After former Meta employee and federal whistleblower Frances Haugen leaked internal Meta documents to the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2021, the company’s impact on teens came under close scrutiny. Haugen alleged that Meta knew its app Instagram adversely affected the mental health of teen girls but buried its findings. Meta has denied the claims.

Since then, Meta has rolled out safety features: Spokesman Andy Stone told the Washington Post in March that the company has developed “more than 30 tools to support teens and their familiars.” While the latest safety features are a “baby step” in the right direction, the company also may be trying to assuage parents and lawmakers while avoiding a major overhaul, said Kris Perry, executive director of tech advocacy nonprofit Children and Screens.

“What worries me about this is that it’s asking parents to surveil children through an option the platform’s giving them, rather than the platform taking responsibility for making its products safe,” said Perry.

The share of teens who use Meta-owned Facebook has dropped significantly during the past few years, from 71% in 2014 to 32% in 2022, according to data from the Pew Research Center. But Instagram is still widely used among people ages 13 to 17, with 62%t of teens using the app compared with TikTok’s 67% and YouTube’s 95%.

Messenger is the third-most-downloaded communication app in the United States, behind Meta’s WhatsApp and Snapchat, according to analytics company SimilarWeb.

On messaging apps, teens run into unwanted or inappropriate outreach from peers and adults. A 2021 study from University College London found that 75% of adolescent girls had received an image of a penis on social media, most often unsolicited. The study called out Snapchat and Instagram, saying the latter “facilitates unwanted sexual content through its direct message and group chat features.”

The features and tests Meta unveiled Tuesday – such as blocking image messages from accounts you don’t follow – focus on protecting users from harassment and abuse.

“We want people to feel confident and in control when they open their inbox. That’s why we’re testing new features that mean people can’t receive images, videos or multiple messages from someone they don’t follow, until they’ve accepted the request to chat,” Cindy Southworth, head of women’s safety at Meta, said in an email.

“To help prevent unwanted contact from strangers, by default we only allow teens to send messages to another Snapchat user they are already friends (with) or have in their phone contacts. We regularly strengthen our tools for detecting and reporting sexual content,” Snap spokeswoman Rachel Racusen said in an email.

Not everyone celebrates more expansive parental controls. Some civil liberties experts say increased visibility for parents often comes at the expense of privacy for teens. Adolescents who live in abusive or homophobic homes, for example, may benefit from autonomy and private connections online: Online-only friendships have been shown to protect vulnerable teens who experience suicidal ideation.

Child-safety experts recommend parents frame their involvement in kids’ online activities as collaboration, not surveillance. Building connections online is part of life for contemporary teens, said Melissa Stroebel, vice president of research and insights at Thorn, an organization that builds technology to combat child sexual abuse. The distinction between “stranger” and “friend” isn’t always clear, she said, so it is important that parents help children think through the differences between a safe and unsafe contact.

“Conversations about who they’re interested in talking to and why can in time evolve into talking openly about the quality of those connections and what is safe and healthy to be exploring with those friends,” Stroebel said.