Your Money Adviser: Hardship 401(k) withdrawals,explained

Hardship withdrawals from workplace retirement accounts are edging upward – another sign, along with rising credit card debt, that Americans have been feeling financial pain from inflation.

“Their budgets are stretched thin,” said Luis Fleites, the director of thought leadership at Empower Retirement, one of the largest retirement plan administrators.

Hardship withdrawals – which involve taking funds from a workplace retirement account early because of an urgent need – increased by 24% over the 12 months that ended Sept. 30, according to an Empower report released in November. The findings are based on an analysis of 4.3 million accounts in corporate retirement plans that Empower administers, and a survey of about 2,500 Americans. (The pace of inflation has slowed recently but is still unusually brisk.)

Other big plan administrators reported increases in withdrawals as well. Vanguard, which administers accounts for about 5 million people, said nearly 0.5% of 401(k) participants took a new hardship distribution in October of this year compared with 0.3% in October 2021.

Fidelity Investments, the largest retirement plan administrator, said that while numbers were still “relatively low,” 2.2% of 401(k) participants took hardship withdrawals between January and October of this year, compared with 1.9% for all of 2021.

Hardship withdrawals can be made for “immediate and heavy” financial need, according to the IRS, to pay for things like medical bills, a down payment for a new home, college tuition, rent or mortgage to prevent eviction or foreclosure, funeral expenses and certain home repairs.

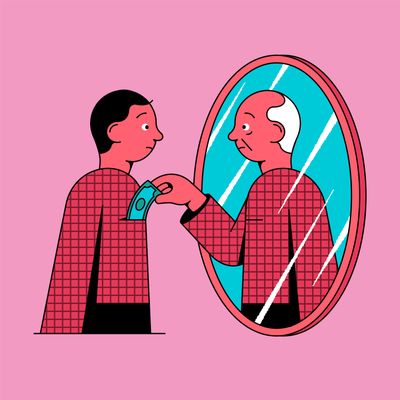

The withdrawals may solve a short-term issue, but they come with downsides. Employees generally can’t take money out of a 401(k) or similar account before age 59½ without owing a 10% penalty (some exceptions apply), in addition to ordinary income taxes.

That means workers may have to withdraw more than they actually need, unless they have other funds to cover the taxes. If you need $15,000, you would have to withdraw nearly $24,000 to pay taxes and penalties, according to an example from Fidelity. (The example assumes 20% for federal taxes, 7% for state taxes and a 10% penalty.)

Plus, you can’t repay the money to the account or move it into an individual retirement account, so withdrawals permanently reduce your retirement nest egg. (Those rules were temporarily relaxed in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic, allowing people to return funds to their accounts and waiving the penalties for hardship withdrawals.)

Hardship withdrawals should be a “last resort,” said Joni Alt, a senior wealth adviser at Evermay Wealth Management in Arlington, Virginia. She suggested exploring other alternatives first, like a home equity line of credit.

Jeanne Sutton, a certified financial planner with Strategic Retirement Partners in Nashville, Tennessee, said that in her experience, the top reasons for hardship withdrawals are medical debt and the purchase of a new home.

“Most of the time, they don’t have options that are better,” Sutton said.

People with large medical bills should try to negotiate a payment plan before tapping retirement funds, she said.

Absent other options, a loan from a 401(k) may be better than a withdrawal, Sutton said, as long as you pay it back on time – and don’t make it a habit. You won’t owe taxes and penalties with a loan. You’ll pay interest – but you’ll be paying yourself because it will go back into your retirement account.

The downside is that you will lose out on potential long-term market gains on the funds you borrowed.

“You lose the greater value, which is the value of compounding,” said Jeff Cimini, the senior vice president of retirement product management at Voya Financial.

And taking out a 401(k) loan may be particularly risky if you’re worried about job security because some employers may require you to repay it quickly if you leave your job or are terminated.

Loans from 401(k) accounts have become less popular since the 2008 financial crisis as rules for hardship withdrawals have become more flexible, according to Vanguard. Federal legislation in 2018, for instance, eliminated the requirement that workers must take out a loan before taking a hardship withdrawal.

Still, some data shows that loans from 401(k)s have also ticked up recently. Empower said loans increased by 13% between September of this year and last. Vanguard said 0.9% of its plan participants borrowed from their retirement accounts in October, up from 0.8% at the beginning of the year.

Fidelity, however, said the proportion of 401(k) savers taking out a new loan remained “low,” with 2.4% of plan participants doing so in the third quarter of this year.

Here are some questions and answers about hardship withdrawals and loans:

What’s the best way to avoid hardship withdrawals?

Having an emergency savings account is critical because people with rainy-day funds are far less likely to tap into retirement accounts when there is need, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

But nearly one-quarter of consumers have no funds set aside for emergencies, according to a March report from the bureau. More employers are starting to offer emergency savings options to help workers avoid early withdrawals from retirement accounts. Under legislation pending in Congress known as Secure Act 2.0, employers would be able to automatically enroll workers in emergency savings plans more easily to increase participation, much as they already do with retirement savings plans. The proposal has “good bipartisan” support, Cimini said. But time is running out for lawmakers to act before the current session expires at the end of the year.

Should I continue contributing to my 401(k) if I take out a loan or hardship withdrawal?

Yes, if you can afford it. “They absolutely should keep contributing,” Sutton said. (A requirement that workers pause contributions for six months after taking a hardship withdrawal was repealed, the IRS said.)

Do all retirement plans allow hardship withdrawals and loans?

While they’re not required to, most do. Check with your employer for your plan’s rules.This article originally appeared in the New York Times.