Shawn Vestal: A Black pioneer’s legacy in Spokane stretched deep into the 20th century

He was born into slavery and escaped it.

Joined the Union Army and marched with Sherman to the sea.

Served two terms in the Mississippi Legislature during Reconstruction.

Then he, his wife and seven children moved to Spokane, where – as one of just a handful of Black residents here at the end of the 19th century – he helped found the city’s first Black church, served as a pastor, bought land and went into business, pushed to improve the lot of farmers and Black people, and ran for the state Legislature.

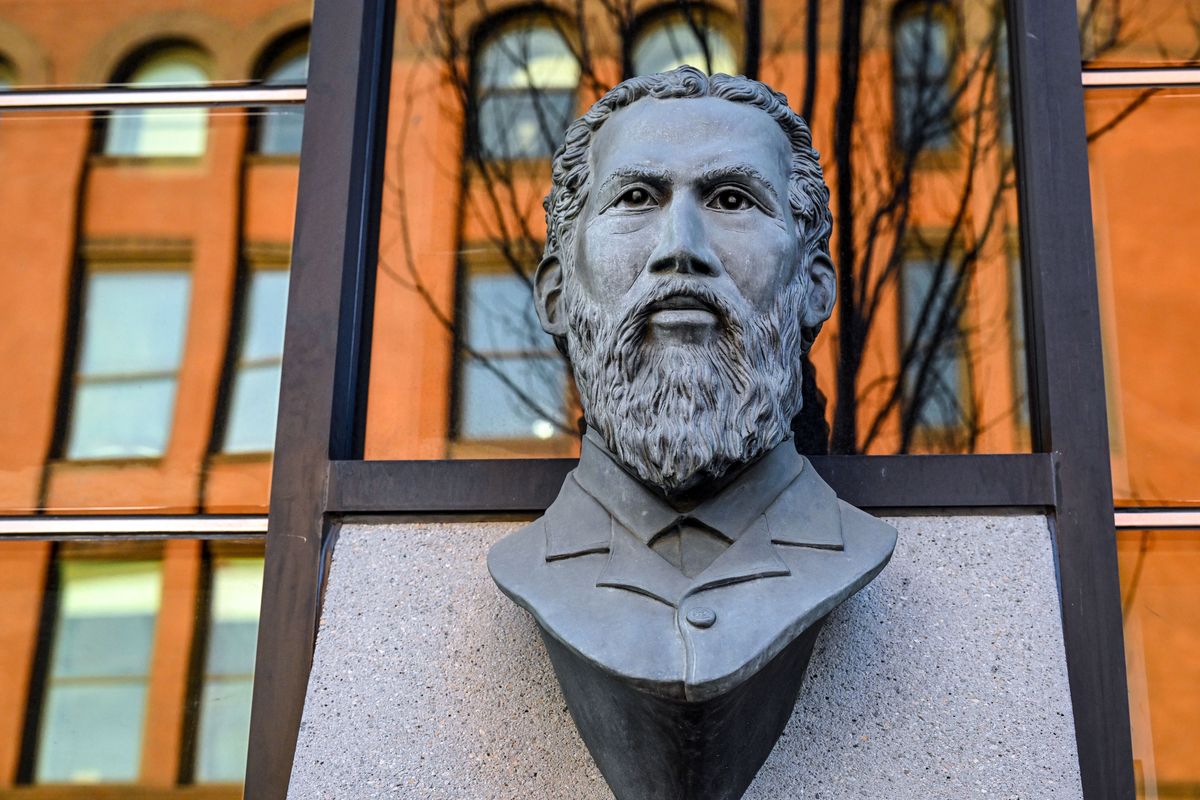

You might imagine the story of Peter B. Barrow would be more widely known. He was an instrumental figure in the city’s early history, and his legacy includes three generations of descendants who were similarly instrumental – none more so than his granddaughter, Eleanor Barrow Chase, who was married to former Mayor Jim Chase and a prominent figure in her own right during the 1970s and ’80s.Barrow is not forgotten, exactly. His story is touched upon – with the few details available in the historical record – in books and articles and on websites. A bronze bust of him hangs on the outer wall of The Spokesman-Review’s production facility, alongside other historical figures.

And yet he is not as widely known as you might expect, and information about his life is scant.

“I never heard about him in elementary school, never heard about him in middle school, never heard about him in high school,” said Betsy Wilkerson, a Spokane City councilwoman and board director for the Carl Maxey Center. “I never heard about him until I was an adult.”

Kurtis Robinson, head of the local NAACP, echoed those comments. For many white pioneers who were important figures in Spokane’s founding, there is much more information in the record. With Barrow and other historical Black figures, he said, “It’s thought of as this separate thing, and it takes a lot of digging to find it.”

Barrow helped start Calvary Baptist Church; the cornerstone of the church has his wife’s name etched on it. His son, Charles Barrow, operated the city’s first Black newspaper and ran an orchard company on the family’s Deer Lake acreage.

If you map the points at which Barrow and his family influenced – or brushed against – Spokane’s history, you find it everywhere: He had a home in what is now East Central – on land that is now owned by the state, on the north side of the freeway that severed that historically Black neighborhood from the life of the city.

One of his sons worked at Louis Davenport’s famous waffle tent, which preceded his famous hotel, and for the Spokane Club. Another was a “printer’s devil” – or assistant – at The Spokesman-Review.

With Eleanor Chase, the third generation of the Barrow family achieved a particular prominence. As important a figure as Jim Chase was in the city’s history, Eleanor left an equally large imprint.

It comes as no surprise that much of Black history has been hidden, distorted, unrecorded and overlooked. For decades and decades, it didn’t make the newspapers, wasn’t written about much in books. In the era when the Chases were prominent, Eleanor often spoke of her grandfather, telling the few fascinating details of his life – and noting how little was known about him and his family.

“Not much was said because I don’t believe they realized they were making history,” Eleanor Chase told a crowd at Spokane Falls Community College in 1978. “They were too busy eking out a living.”

‘The writing on the wall’

Peter Barrow was born as a slave in 1840 near Petersburg, Virginia, and then taken as a child to a plantation in Alabama, according to Union Army Pension Records cited in several histories.

Little is known about his early life, but a profile of him on the website blackpast.org says that when the Union Army came through the area in 1864, “Barrow took his freedom and reached Vicksburg, Mississippi, where he enlisted in Company A, 66th U.S. Colored Infantry on March 11, 1864.”

He served in Louisiana and Arkansas, and remained in the Union Army until March 1866. Many of the brief histories that mention him say he participated in Gen. William T. Sherman’s “March to the Sea” in November and December 1864 – a 37-day campaign to break the Confederacy by uprooting rail lines, burning buildings and crops, and destroying infrastructure between Atlanta and Savannah.

After the war, Barrow settled in Mississippi, where he served two terms in the Mississippi Legislature in the 1870s.

In an oral history project for Washington State University, Eleanor Chase said in 1972 that she wasn’t sure why her grandfather came to Spokane – beyond the fact that he had a friend who had come here first – but it wasn’t hard to see why he would want to leave the South, given the tumult and racism that poisoned efforts to reintegrate free Blacks into Southern society.

“He could see the handwriting on the wall,” Chase said.

Arriving in Spokane shortly after the Great Fire of 1889, one of Barrow’s first activities was helping to start Calvary Baptist in 1890. Barrow was a pastor there for several years. Shortly after that church was formed, a second important Black church was founded: the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Wilkerson noted this theme through Black history – pioneering figures leaned on religion to help organize and provide community and solace. Churches were “our safe spaces” in a society that was short on them, she said.

As Jerrelene Williamson wrote in “African Americans in Spokane” – an indispensable account of Black Spokane’s history – churches were the center of cultural life, hosting not just services, but also picnics, dances, contests, ice cream socials and ball games.

“The African American churches in Spokane were the lifeblood of their people,” she wrote.

A civic leader

Peter Barrow had a home in Spokane, in what is now known as East Central, and owned property at Deer Lake as well. The Deer Lake acreage was agricultural land, and Barrow’s farming activities were a key part of his political life, as a leader of the Farmers Alliance Movement.

That movement focused on using cooperatives and political action to improve the lives of farmers.

Barrow also ran twice for the state legislature, unsuccessfully, as a Populist Party candidate, and formed the John A. Logan Colored Republican Club.

All of this played out at a time when Spokane’s Black population was quite small – the 1900 Census recorded 376 Black people here. Yet Black Spokanites owned a few businesses, including a real estate company and the Poodle Dog Cafe downtown.

Barrow was a well-known figure in town, and his activities often earned brief mention in the newspapers. And yet the level of historical detail about his life is scant. He died in 1906, at age 66, while he was in Tacoma for a church conference, as reported by The Spokesman-Review.

“While crossing the street he was run into by a (street) car and seriously hurt,” the article reported. “He was at once removed to a hospital, but medical aid could not save his life.”

An obituary said: “Rev. Barrow’s death has been greatly deplored among all classes and citizens, who have known him so long and favorably, and many tokens and messages of condolence have been received by the bereaved family.”

The obituary also noted that he had “accumulated a comfortable competency,” pointing to his ownership of property and his political activism.

The Tacoma Railway and Power Co. later paid the family $150 to settle a claim arising from the accident.

Carrying it forward

Two of Barrow’s seven children dominate what little historical record exists about the family’s next generation – Charles and Peter Jr.

Peter Jr. worked in his early years at the Spokane Club; this was a common place of employment for the city’s African Americans at the time, waiting on tables and working in the coat check room and in other service positions. He was also there at the start of Louis Davenport’s landmark hotel project, working in the tent where Davenport sold waffles while trying to recover after the Great Fire.

Davenport went on to open a waffle factory and then the famous namesake hotel downtown.

Charles worked at The Spokesman-Review, where he learned the printing trade while working as a “printer’s devil and errand boy,” according to a handwritten family document included among records in the Spokane Public Library’s Northwest Room.

Charles went on to open his own business, X-Ray Printing, which was later renamed Quality printing, and ran it for four decades. Charles also published Spokane’s first Black newspaper, the Citizen, between 1908 and 1913.

One particular issue of the Citizen, published in 1912, focused on a major family project: the Deer Lake Irrigated Orchard Co. Peter Sr. was an advocate for cooperative ventures and for using the family’s land to help other Black families prosper, and his sons seem to have carried forward that spirit.

A newspaper ad archived at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture says the brothers formed the company in 1910 “to provide area African Americans a business ownership opportunity.”

That 1912 issue of the Citizen – a photocopy of which is archived at the library’s Northwest Room – extolled the promise of the project, offered shares at $1 each, and promised annual returns of 20%.

“The Perfect Apple is the UNIVERSAL FAVORITE of Fruits,” the newspaper said.

More than 40 stockholders invested around $18,000 in the company, according to the historical web site blackpast.org. The Citizen included photographs of many investors, and they included several African American residents of Spokane along with others from Chicago and St. Louis.

Though the project focused on apples, Peter Barrow Jr. also raised strawberries and developed a reputation for them, Eleanor Chase said in her 1978 speech at SFCC. A photo in the Citizen issue about the Deer Lake project shows a mound of berries, each nearly as big as the silver dollar included in the shot for scale.

The brothers also built a small resort on the lake, at a spot on the east side of the water then known as Barrow Beach. It had three or four cabins, and was used primarily by friends and family, Chase said.

She said the company existed for only a few years before running into financial difficulties.

“I would say it might have lasted 10 years,” she said in the interview with the WSU archivist.

The third generation

Eleanor Chase was born in 1918 and grew up in a home on East Second Avenue that was a central gathering place for many in the community, according to accounts in local newspapers.

“Mrs. Chase’s mother, Mrs. Charles S. Burrow, one of the early blacks in Spokane, was a genial, welcoming face to thousands of Spokanites when she operated the coat-check cloakroom at the Davenport Hotel for many years,” wrote columnist Dorothy Powers in The Spokesman-Review in 1983.

The family home was “the gathering spot for all Spokane’s young black people – a place filled with the smell of warm baked goods, where welcoming parents were always ready to set one more plate,” Powers wrote.

And yet the early prosperity of the family faded during the Depression. Chase recalled her father bartering work for food and clothing during the 1930s. Her father operated the printing company until his death in 1950.

Eleanor stood out from the early years of her life, excelling in academics, music, and community organizations. She graduated with honors from Lewis and Clark High School and Whitworth College, with a music degree in piano and voice.

As a teenager, she met James Chase – who had come to Spokane from Texas, he once said jokingly, because “we liked the propaganda that the Chamber of Commerce sent out.” They married in 1942.

Jim ran an auto-body shop with a friend who moved here with him from Texas. He was president of the city’s NAACP chapter during the 1960s, and a vocal leader on civil-rights issues. He ran unsuccessfully for City Council in 1969, and then successfully in 1975. His council tenure was marked by a focus on government transparency and efficiency, and on sustaining youth programs.

He won the 1981 mayoral election by a landslide; he was the city’s first, and the state’s second, African American mayor, and he received national attention in subsequent years for his political achievements and his steady, nonconfrontational approach.

At every step, Eleanor received as much – and sometimes more – public attention as her husband, and their marriage was often held up in the local press as a model of committed companionship.

And she was a constant presence in her husband’s political life. When he was elected mayor, The Spokesman-Review ran a story headlined “Eleanor Chase: A profile of devotion.”

In 1985, she said of her husband, “We are one. We have seldom been apart. I’ve idolized him ever since we met.

After staying home to raise their son, Roland, Eleanor served as a social worker and juvenile court officer; she sang in choirs and performed all around town, and was considered a singer of professional quality; she eventually served on the boards of trustees for Eastern Washington University and Whitworth.

Her attendance at every City Council meeting was noted frequently in the local press. She was involved in scores of civic organizations, from the YWCA to the NAACP to the Order of the Eastern Star to the Optimists Club, and was a particular advocate for early childhood education.

Jim died in 1987, and Eleanor in 2002. Their son, Roland, who worked for many years at the Spokane County Courthouse, died in 2019.

The Chase legacy – which is also the Barrow legacy – is woven into the community. A work-release center was named for Eleanor Chase. The Chase Gallery welcomes visitors to the lower level of City Hall, and thousands of Spokane students have been taught at Chase Middle School.

They are reminders of a history that goes much deeper than it might seem.

“The foundation we stand on now was instrumental from the work they did,” said Robinson, the NAACP president, referring to Peter Barrow’s generation. “And it’s our responsibility to carry it forward.”