36-year-old was dead in the Garfield County Jail for over 18 hours before corrections staff noticed, complaint alleges

Kyle Lara and his daughter are pictured in this family photo. (Courtesy of the Lara family)

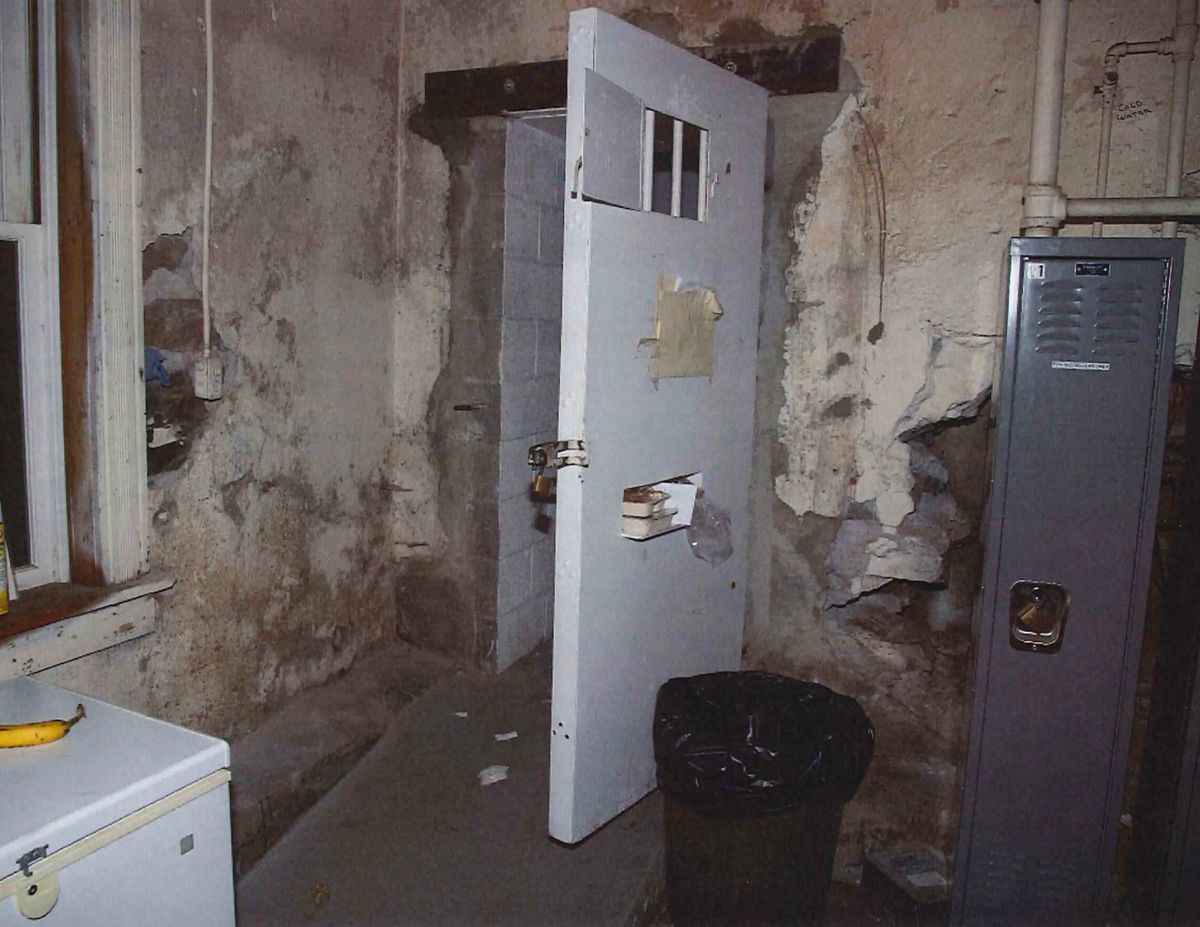

A 36-year-old man was dead in a “dungeonlike” cell at the Garfield County Jail for more than 18 hours before dispatchers who monitor the jail noticed, a complaint filed Thursday alleges.

Kyle Lara died April 14, 2022, when he hanged himself in his cell while awaiting trial in Pomeroy.

An $8.5 million claim against the county filed by his family alleges the county housed him alone in the basement of the courthouse built in 1901 after he expressed suicidal ideations.

“This never should have been allowed to happen. As a parent to a young man with addiction issues, sometimes I prayed that my son would get picked up because he is ‘safer’ in jail than on the streets,” David Lara, Kyle’s father wrote in a statement. “I trusted the system. I trusted that the government would abide by the law and provide reasonable care to my son. My trust has been betrayed. Now, all I can hope for is some semblance of accountability.”

Lara was arrested in March after a domestic violence incident, in which he called the police alleging his girlfriend punched him, according to court documents. When Deputies arrived, they noticed she had a red mark on her neck, which she said was caused by Lara grabbing her throat. He was charged with second-degree assault and unlawful imprisonment.

It wasn’t Lara’s first brush with the law. He had been in jail for a series of misdemeanors starting in 2007, when he was a teenager.

He had several felony convictions, mostly related to drugs. His most recent conviction was for evading police in California in 2017, according to court documents.

Lara had managed to stay out of trouble for years before his 2022 arrest.

When he arrived at the Garfield County Jail, located in the smallest county in the state, Lara “made suicidal statements,” according to the claim. He punched a wall, breaking several bones in his hand.

Undersheriff Calvin Dansereau told the Washington State Patrol that it wasn’t Lara’s first time voicing suicidal ideations.

“He’s threatened (suicide) like every time we arrest him,” Dansereau said.

Dansereau treated Lara’s statements as normal, housing him in general population, the claim alleges.

Not long after, Lara got into an altercation with a fellow inmate and was moved into solitary confinement, in part because of the prior suicidal statements, Dansereau told investigators.

Putting high-risk inmates in isolation is “like throwing gasoline on a fire: extremely dangerous” the claim argues, citing a Florida federal court ruling.

The jail is “monitored” by civilian dispatch officers via surveillance cameras, Dansereau and Garfield County’s Emergency Management Director, Tina Meier told WSP. Typically there’s one dispatcher working at a time, who uses a single computer screen to take dispatch calls and monitor the 20 jail cameras.

Dispatchers take 911 calls; dispatch officers, emergency medical and fire personnel; enter warrants and protection orders; monitor and serve meals; and administer medication to those in jail, Meier told WSP.

Correctional facilities in Washington state are required to be staffed with certified officers, said Ryan Dreveskracht, the family’s attorney, who also serves on the state board that trains and certifies peace officers.

While dispatchers monitor the jail, they’re not allowed to have any face-to-face contact with inmates, aside from passing meals through slots in cell doors. If a cell door needs to be opened, dispatchers must call one of four county sheriff’s deputies, the claim alleges.

The county doesn’t have policies on how often dispatchers are supposed to check on inmates in isolation, Meier told WSP.

“These dispatch officers are tasked with things way beyond what they are trained to do,” Dreveskracht wrote in a news release. “They can’t do their jobs as dispatchers and adequately monitor and take care of inmates at the same time – that’s what correctional officers and correctional medical professionals are for.”

Between April 6 and 10, Lara was erratic, blocking the cameras in his cell and threatening dispatchers, the claim says.

On April 13, Dansereau told Lara he would be relocated to the Walla Walla State Penitentiary, where Dansereau knew Lara did not want to go.

At about 8 p.m. Lara can be seen on video putting a white sheet up to cover part of his cell, the claim alleges.

If inmates hang a bed sheet, dispatchers are required to contact the inmate and tell them to remove it, the claim says. If they refuse, a deputy should be called.

The lone dispatcher on shift did nothing, the claim alleges.

At about 10:20 p.m., Lara can be seen writing what turned out to be a suicide note that was later found in his cell, according to the WSP investigation.

At 11 p.m., Lara can be seen going behind the sheet into the shower area, where he hanged himself.

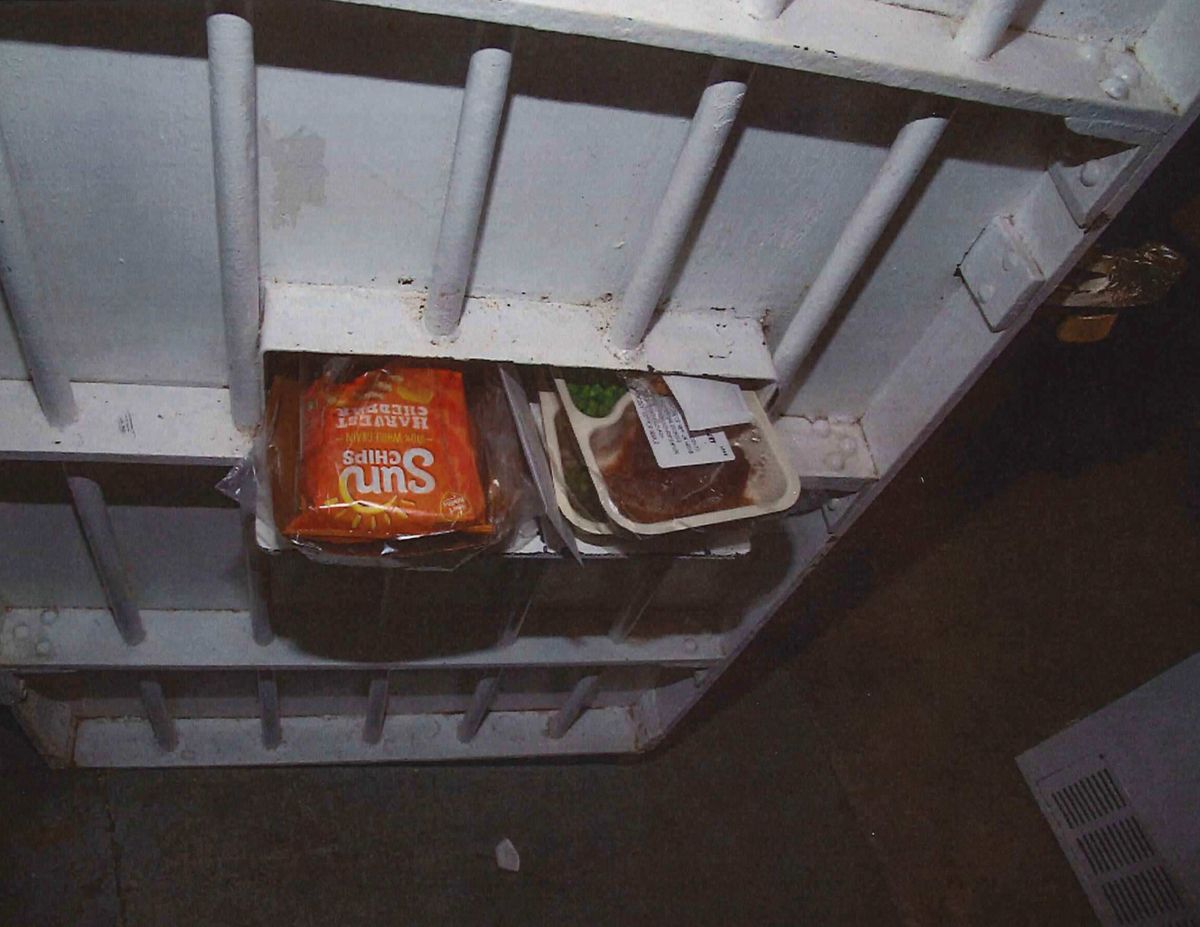

Just before 7 a.m. the next day, the dispatcher on shift overnight placed Lara’s breakfast into the slot in his cell door.

The next dispatcher, who arrived a short time later didn’t go to his cell until lunch time, when she noticed Lara’s breakfast had gone untouched.

The dispatcher shoved his lunch in the slot on top of the untouched breakfast and continued with her shift.

At 4:30 p.m., the dispatcher on duty noticed Lara’s breakfast and lunch still sitting there. When the dispatcher called at the door, there was no response.

A deputy arrived just before 5 p.m. and opened the door, discovering Lara dead, the claim says. It was clear Lara had died hours before he was discovered.

The Garfield County Sheriff’s Office did not issue a news release about Lara’s death when it occurred, a customary practice, according to the Lewiston Tribune.

The sheriff’s office asked WSP to investigate, according to the case file.

The WSP investigation confirms that the jail is not staffed full time but instead monitored via video by dispatchers. Investigators did not recommend any charges in connection to Lara’s death.

The Garfield County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to request for comment.

Had the jail been property staffed and Lara properly monitored, his death could have been prevented, the claim alleges.

“Kyle had problems – don’t we all – but he was still a person; a father, and a son. He still deserved to be treated with dignity and respect. And he didn’t get either,” Rhonda Lara, Kyle’s mother said. “The County served 2 meals to his dead body. How am I going to tell his daughter that? How am I going to explain to her that this is why she doesn’t have a daddy?”

The county has 60 days to reply to the tort claim, a necessary step before a lawsuit can be filed.