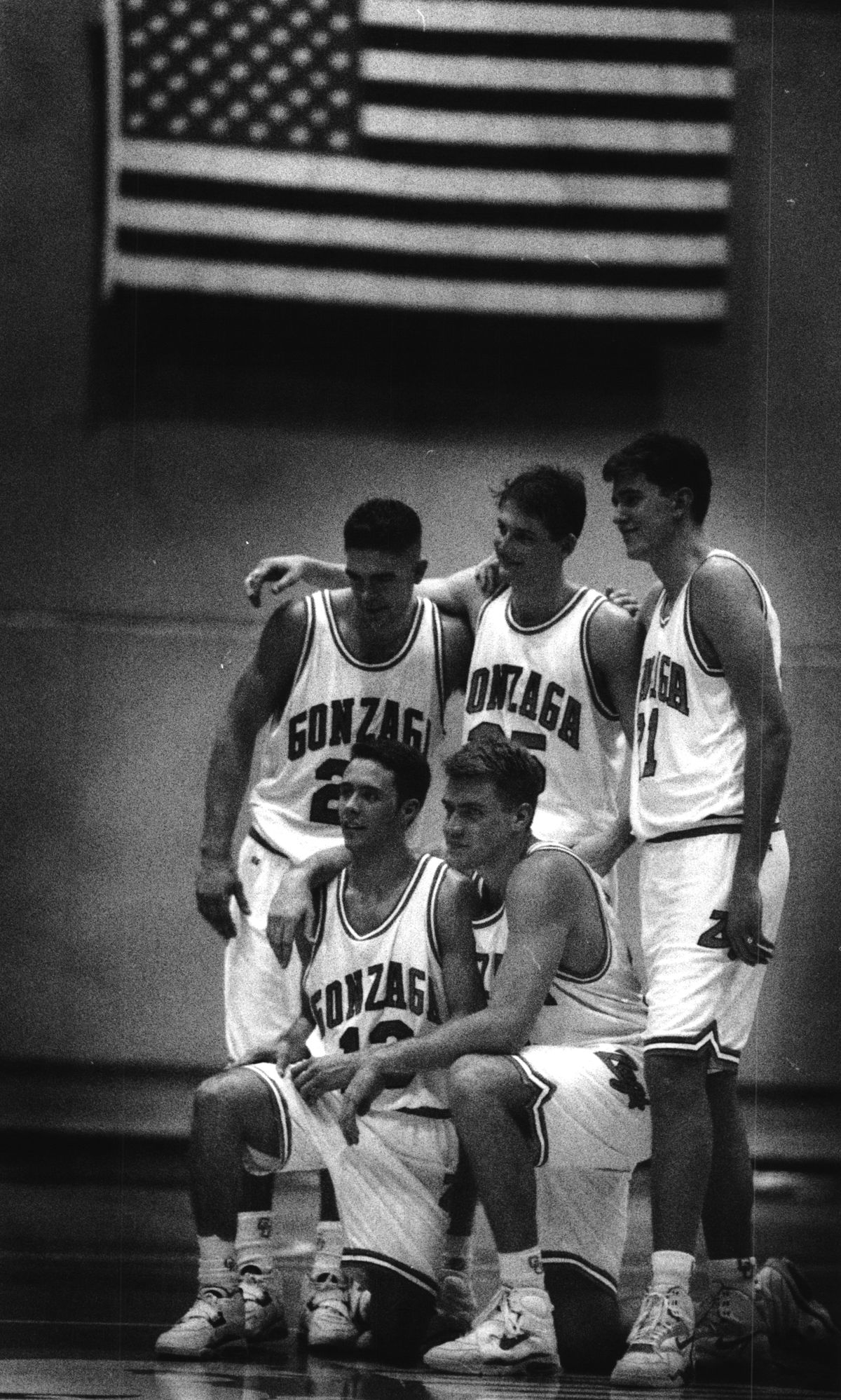

An oral history: Gonzaga’s last losing season came nearly 35 years ago. During a preseason scrimmage, six redshirts made a statement to the varsity that times were about to change.

As often happened during the bleak 1989-90 season, the Zags were getting clobbered by a more talented opponent.

Unseen by the public, unreported in the news, this loss didn’t count against the 8-20 record that season.

In fact, this lopsided defeat came before the basketball season officially started, pitting the varsity against six newly acquired redshirts in an intrasquad scrimmage.

Of the four freshmen, three were walk-ons.

Two promising transfers bolstered the group, one a skinny late-bloomer who knew he needed a season to bulk up, and another who had been so disappointed with his first two years at another school that he considered giving up basketball altogether.

The varsity unit was led by the redoubtable Jim McPhee, a Founding Father who passed down so many of the finest Zag traits – a player more admirable given his consistent performance amid this season of historic futility.

But even McPhee was not enough to fight off the competitively rapacious redshirts as this early scrimmage marked an eye-opening pivot in GU hoop history – the point when it turned from what it always had been toward what it would eventually become.

From that season on, no other team in Gonzaga men’s basketball history would have a losing record.

The Redshirts

The six brash young Zags who sat out that year – with a varying range of talents and prospects and maturity – were unified with by a common circumstance: Each had something to prove.

Scott Spink, from Sehome High, was the lone freshman with a scholarship. Point guard Geoff Goss (Boise High) had family members contact head coach Dan Fitzgerald to lobby him for a walk-on position.

Center Marty Wall was a legacy, his father had played at GU in the late 1960s.

Forward Matt Stanford (Blanchet High in Seattle) was offered a scholarship but had it revoked at least for a year when Fitzgerald learned that Stanford’s father was a professor at Seattle U. and he could pay for his own tuition at 20 percent the normal rate and save Fitzgerald a valuable ride.

Jarrod Davis was a wisp, at 6-2, 150-pounds, when he left Mead High for Tacoma Junior College two years earlier. He was eligible to play at GU immediately, but knew he needed to be stronger for the Division I competition, even turning away from recruitment to Washington State because coach Kelvin Sampson didn’t want to redshirt a jaycee player.

The other player was Eric Brady, required to sit out in observance of the transfer rules (remember those?). It was a time for Brady to heal his relationship with basketball. The State Player of the Year at Mercer Island, had languished on the bench for two seasons at UW.

Stanford: “There was kind of an ego check we all had to go through from the way we showed up to the program. New recruits often come in thinking they’re really something, but we all came in thinking we had something to prove.”

Goss: “I assumed I was going to redshirt because I wasn’t anywhere near mature enough to play.”

Davis: “They kind of found me late. I wanted to redshirt. I was up to 175 pounds and 6-6. So, I needed to redshirt. I think all of us were a little naïve, and we were all raw. Goss was stupidly athletic but had no idea how to play. Brady and I were a little bit of misfits. It was a unique group of guys in a very transformational time.”

Misfits? Perhaps, but they all suddenly fit as Zags.

Brady: “We had a really good group – four young and talented guys out of high school and two transfers. Jarrod coming off two really good years in junior college and I was crawling out of the trash heap at UW. We also had a young graduate assistant whose primary responsibility was to coach the redshirts. That was Mark Few’s first year as a college coach.”

Spink: “Brady was steady and mature and calm. Jarrod was just fiery and wanted to win and talk (trash) and wouldn’t back down from anybody. (We freshmen) watched that combination and thought, ‘oh, this can be fun’.”

Goss: “Early in the fall, before practice even started, we were playing pickup and (Fitzgerald) pulled some of us aside and told us he wanted to redshirt us because it was a pretty good group and he wanted to keep us together.”

The Scrimmage

Memories vary on the final score and individual statistics, but nobody involved forgets the relevant point: The redshirts easily defeated the varsity in a Saturday scrimmage early in fall practices in 1989.

Goss: “Jarrod had about 50 (points) and Eric had about 30. We played 60 minutes, three separate 20s, and I specifically remember watching Jarrod light these guys up and Eric killing people from all over. I felt lucky to just be on the floor with them.”

Spink: “It was so much fun; I still remember some sequences from that game, getting a fullcourt bounce pass from somebody and (one of the varsity players) coming at me, thinking he’s going to block my shot, and I’m thinking, ‘sorry, but you don’t have a chance’.”

As Spink recalls, coach Dan Fitzgerald added a third “half” of 20 minutes to give the varsity the chance to rally. It just got worse. Goss and Davis recalled that, at one point, Fitzgerald turned off the scoreboard to protect the confidence of the veterans.

Davis: “Fitz was like holy (expletive), what is happening? I think I had eight or nine 3s. We were all naïve, but we were sure we could beat these guys.”

Wall: “Jarrod got hot, and when (the varsity) turned the ball over, Goss and Stan(ford) and Spink were such excellent finishers on the fast break. We had the opportunity to lay it to them pretty good that day.”

Stanford’s memory of that early scrimmage was not as vivid as was his recall of another scrimmage with a different outcome.

Stanford: “What I remember more was later in the year when they finally beat us and they were high-fiving and cheering and being so excited. These were the guys who were competing in the games and we were the redshirts, but they were excited about beating us.”

The Young Coach

The new Zags that season shared a consensus on another matter: The new graduate assistant coach – with a powerful belief they could be agents of change – fit them perfectly.

Mark Few was just 26, with scant resume as a high school assistant. If there were any early eye-rolls regarding his lack of experience, concerns were quickly dismissed.

Goss: “He was very, very competitive, and even though he’d come from high school basketball and hadn’t really played that much, he really knew the game. The one thing that really came across was the confidence he had. He told us that if we keep working, we had the chance to be really good.”

Stanford: “When I think about it now, my early impressions were that he always thought that what was going on (at GU) could be bigger than it was. He had that vision. I saw it from Day One.”

Davis: “We all had that underdog mentality. We were like, we’re good enough to beat the guys we’re playing, we’ve got to play (better) guys. That was always Mark’s mentality. Why are we playing Eastern Oregon?”

Spink: “He could be a pain in the ass: So demanding, nothing was ever good enough. (But that made you) continue to get better. He would always say, ‘it’s shocking we’re not better than we are,’ or ‘why have we never won a league title?’ Those are the kind of comments that stick with you, and get under your skin.”

The Veterans

Jim McPhee was revered. Senior point guard Mike Winger, too. McPhee averaged 23.6 points a game in the ‘89-‘90 season. In the two regular season games against nationally ranked Loyola Marymount, he scored 42 each time.

Still, the Zags scored a mere 68.1 points a game, 242nd out of 292 Division I teams in the country, and attendance averaged a paltry 1,960.

The conference losing streak stretched to 10 games between mid-January and mid-February, but on their final road swing in the Bay Area, they beat San Francisco and Saint Mary’s.

Stanford: “I just love Jim McPhee. I was, like, if I could ever be like that guy, with his level of commitment and intensity. I particularly felt bad for him; what a tough thing to be an all-league guy on a team that just didn’t have the pieces to be competitive.”

Spink: “I loved Jim and Mike. McPhee … if you could model your life after one guy, Jim McPhee is that guy.”

Asked about the celebrated group of redshirts for a Spokesman-Review column in January, 2023, McPhee recalled: “That redshirt team came out to kill us in practice, and a lot of times they did. They were really cohesive and good guys.”

Spink: “I remember them winning two games near the end of the year, on the road. That was a big thing. Fitz never lost them and they didn’t give up. That’s the kind of thing that sticks with you.”

Fitzgerald appreciated the character of the team that season, telling the Spokesman-Review: “I’ll always have a special place in my heart for this team because they kept after it and they didn’t grumble and they never threw blame around.”

Fitzgerald evaluated the season prophetically: “It’s broken, but it’s fixable.”

The Additions

As the redshirts became eligible, further reinforcements arrived incrementally, the most crucial addition being former Mead High center Jeff Brown, a prep teammate of Davis’, who transferred from UW and sat out 1990-‘91.

With Brown watching from the sideline, the ’91-‘92 Zags clawed back up to .500 (14-14) behind Davis’ 19.6 average and all-league play.

Davis: “We got some of the right pieces when Brown showed up. I knew he had a bad experience at UW. I knew his parents and I called his mom and told her that he’s got to come home. I told him, we’ve got a great group of guys. He was the piece we needed.”

The next season (‘91-‘92), the Zags got to 20 wins, going 8-6 in the conference and coming within a few points of an NCAA Tournament berth by losing to conference champ Pepperdine in the WCC Tournament final, 73-70.

Shame to end that way, as it was the final season for Davis and Brady. So close. But it wasn’t enough for an NIT berth as they were still building their profile and reputation.

They got close, again, in ’92-’93, with the 19-9 record including a 10-4 WCC count and a two-point loss to Santa Clara in the conference tournament semifinals.

The Brotherhood

According to some of the Zags polled, players from other teams would marvel at the obvious camaraderie they had developed over the years.

Spink: “We fell in love with each other. It’s so hard to say what happened, but it was good and great, and we had so much fun. I have no idea if people playing college basketball today have as much fun as we did. I doubt it.”

These Zags were convinced that the close relationships made them mutually accountable, and were a key to their achievements on the floor and also in the classrooms.

Spink: “We knew none of us was going to make millions of dollars playing in the NBA. Like that NCAA commercial, we were all going to go pro in something else. I swear, I don’t think any person, the entire time I played, ever looked at their stats or cared about them. Just the wins.”

Goss: “I haven’t seen anything like it in college basketball. We were all in each other’s weddings. Took vacations together.”

Wall: “The tight bond had to do with the collection of characters we had; we all clicked and our personalities were such that we fit well together. And there was a competitive fire within that group.”

Spink upped Wall’s assessment of the group’s competitiveness to “combative.”

Spink: “We were a group of people who just wanted to win basketball games, even scrimmages. We’d get in fights with each other. We would tackle each other and tear jerseys … it was crazy.”

Stanford: “You could see the beginning of creating a culture of having guys who want to be there for the right reasons, who want to commit to being the best they can be. So many guys who are really talented aren’t committed to that.”

The Payoff

They had gone from 20 losses to 20 wins in two seasons, and the year after that they finished second in the West Coast Conference.

Then, with Brown averaging 21 points a game on his way to conference Player of the Year honors, the ’93-’94 Zags rolled through the conference season, winning their first title with a 12-2 record.

But their loss to San Diego in the conference tournament semifinals kept them from earning the automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament. Finally, though, the 22-7 record and regular-season league championship earned an NIT bid, the first post-season berth in school history.

The reward was a road game at Stanford’s Maples Pavilion.

The Zags, now a confident group of veterans rolled to a 19-point lead over Stanford. Brown, who wanted to go to Stanford after high school but was denied, scored 27.

And Goss, who was ignored by teams out of high school, held talented Cardinal point guard Brevin Knight scoreless. Knight would go on to be a first-round NBA draft pick, but Goss owned him, outscoring him 16-0.

Stanford: “(The NIT win) was a huge deal to us, the WCC being the Pac-10’s ugly cousin.”

Spink: “That was one of those games when we just felt we were better than them, we weren’t going to lose.”

The Zags held on for an 80-76 win, earning them another trip, this one to Manhattan, Kansas, where they lost by just two to Kansas State.

The bar had been raised.

After that Stanford game, Fitzgerald, his face still red from an evening of sideline raging, addressed the players with obvious pride in their accomplishment. On his way into the hallway for his post-game interview, he turned to the team: “Clean up your mess. These people have been good to us. Leave it better than you found it.”

It had been the biggest win in his coaching career, but he took a moment to remind his players the importance of being respectful guests.

Their Legacy

“Leave it better than you found it” could be the perfect motto for the group that came to GU in the fall of 1989. It would be hard to speculate how much better Gonzaga basketball had gotten during their tenure, or what would have happened if the staff hadn’t decided to allow the young talent to mature for a year.

At the minimum, they lifted the Zags from last place in the conference to first place, while getting the school’s first post-season bid and victory. The following year, Fitzgerald coached the Zags to their first NCAA Tournament. Four years after that, Dan Monson got them to within a few points of a Final Four berth. The next year, Few started his own streak of 23 straight NCAA appearances.

Brady: “To me, our redshirt group was the first step of many in which the program went from being known only as the school where John Stockton played to a national championship contender.”

Davis: “We all understand (how far) Gonzaga has come to. We played 30 years ago, it’s a different program, we see that. Mark is a Hall of Fame coach, we get that. But it had to start somewhere, and I feel like we all believe it was the culmination when we all came together.”

Goss is a lawyer in Boise. Spink an engineer in the Spokane. Stanford is involved in real-estate in Seattle. Wall is an executive in a food company. Davis is in corporate development in Boise. Brady is a financial consultant.

All stayed close to the program and take pride in its elevation to national prominence.

Davis: “When they beat Florida (1999 Sweet 16), we were all there and rushed the floor and went into the locker room.”

Spink: “Deep down, I think we have a little bit of play in (the GU success). But it was Mark (Few). It was Mark’s incessant drive to make us better. People ask me about that, and I say, ‘we were the clay’ – Mark made it happen. In life, you don’t get to spend much time with transcendent people, but Mark is one of those guys.”

Brady: “The stories about the ’89-’90 redshirts giving the team a daily beat-down have been a bit exaggerated, but I’m okay with it. First 20-win season? Who cares if that includes a number of wins against non-DI opponents? I don’t. I knew the program was in an upward trajectory, but had no idea how far it would go. What a ride it’s been.”