Proposed law would create trust funds for low-income babies to address Washington’s growing wealth gap

(Molly Quinn/For The Spokesman-Review)

Nearly half the babies in Washington are born into poor families.

This legislative session, some lawmakers and the state treasurer are once again trying to pass a proposal they say will break cycles of poverty.

“Within days of one’s birth, people are sent into two different economic trajectories,” State Treasurer Mike Pellicciotti said. “Those families of means who are able to set money aside – set up savings accounts, buy stocks – for that child, and then the 47% of Washingtonians who don’t have those financial means.”

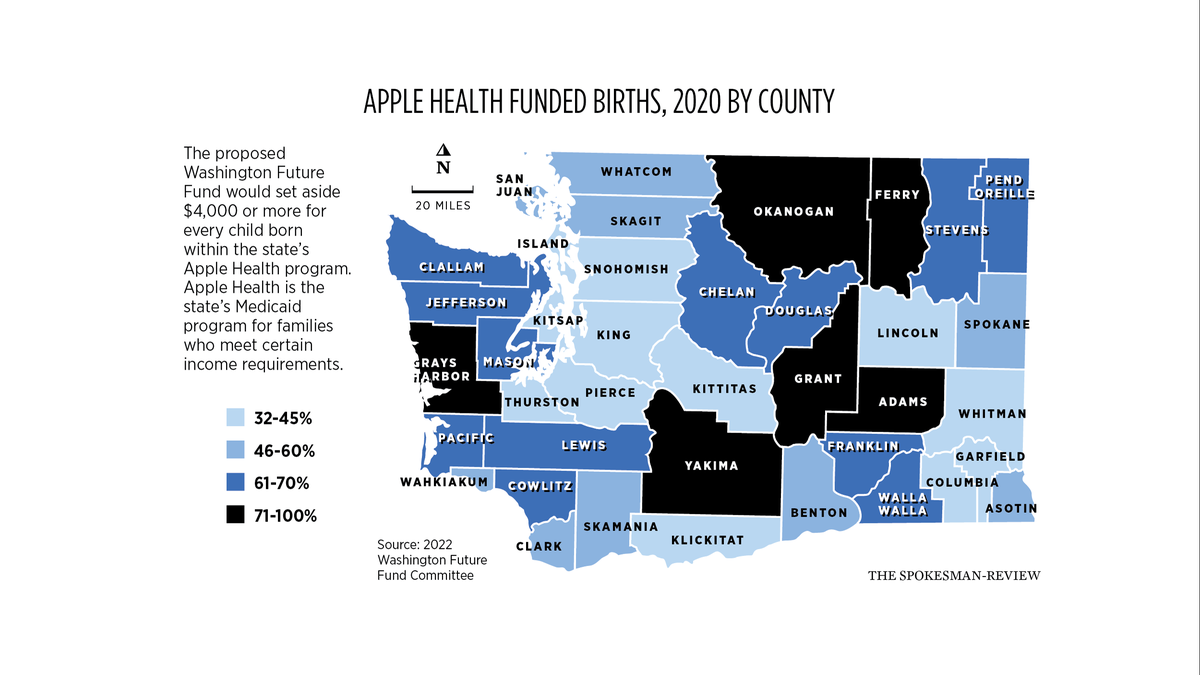

The Washington Future Fund would create a trust fund program for the roughly 40,000 children born each year under the state’s Medicaid program, Apple Health. Those children would be granted access to a trust fund after turning 18 up until they reach age 35 to be used toward homeownership, launching a small business or pursuing higher education.

Along with four-year colleges, Future Fund recipients could use their money to pay for community college and apprenticeship programs. Frequently, young adults don’t have enough money to pay for licensing and trade education.

“The Future Fund is so critical in that initial ability to even engage in the larger economy because of the capital barriers that otherwise limit that person’s ability to even start earning money,” Pellicciotti said.

Under the proposal, a minimum of $4,000 would be set aside for each eligible child to access when they’re 18 to 35 years old. The program would cost the state roughly $125 million annually. The state treasurer estimated the $4,000 trust fund would grow to roughly $15,000 by the time recipients turn 18. And if the recipients wait longer to collect the cash, they could have as much as $35,000 waiting for them in the bank.

Pellicciotti said there might be challenges getting the bill passed this upcoming legislative session because the state won’t enact another budget until 2025. But he said the treasurer’s office pulled in $1.8 billion over the last four years through improved investment returns that could fund the program.

The Future Fund bill – also called the baby bonds bill – picked up bipartisan support in the last legislative session and passed through policy committees in the state House and Senate. It sits awaiting review in the fiscal committees of the House and Senate.

Across the country, the idea of baby bonds gained popularity among state lawmakers in 2020 as Black Lives Matter protests broke out after Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, an unarmed and innocent Black man.

The model was intended to address centuries-old racial and economic inequalities in the United States.

Connecticut and Washington, D.C., recently passed legislation to launch their own baby bonds programs. Along with Washington, other states are currently considering the model, including California, Massachusetts and Nevada.

David Radcliffe is the policy director at the New School’s Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy. He previously served as policy director for the Connecticut Office of the Treasurer when the state passed its own baby bonds program in 2021. The first eligible baby for Connecticut’s program was born July 1. Since then, about 1,000 eligible babies are born in the state each month.

While he supports policies that target income supplementation and housing, Radcliffe said economists and lawmakers need to do more to fix the country’s deep economic inequalities.

“A lot of existing policies don’t necessarily change the income or wealth trajectory for a family,” Radcliffe said. “That is a reason that we continue having to invest considerable resources, year after year, in those areas. But something like baby bonds as part of that larger basket of policies that support families today while investing in tomorrow is a really important consideration. It’s not an either or.”

In Spokane County, 53% of births in 2020 were funded by Medicaid. And more than 70% of births in Adams, Grant, Ferry, Okanogan and Yakima counties were funded by Medicaid. Across the state, racial minorities and rural populations are more likely to be born into poverty than white and metropolitan populations.

Ritzville Republican Sen. Mark Schoesler does not support the baby bonds proposal because a family’s income often improves with time.

“You could for example be born into a family – let’s just say they’re in grad school at WSU,” Schoesler said. “You’re certainly qualified for the program when you’re a kid. But by the time you reach age 16, your family might have a very healthy income because people’s income generally improves with time.”

Pellicciotti noted that the state Constitution bars the state from providing people with state money unless they are in a position of poverty. Therefore, program rules would require that anyone receiving a payout from the Future Fund still had a low income. Under the proposal, a committee would be created to help oversee the program and determine how poverty is defined in accordance with the state Constitution, Pellicciotti said.

Schoesler, a former longtime state Senate minority leader, also worries the program would take away from the state’s current investments in education.

“I represent two universities, and I probably know the students and their parents better than most. They’re tired,” Schoesler said. “Ask the average hardworking taxpayer what they’re paying in taxes. They’ll say they’re already paying too much in taxes to start a new entitlement.”

Spokane Democratic Rep. Marcus Riccelli cosponsored the bill in the state House last year. Medical expenses are still the No. 1 cause of bankruptcy in the United States, he said, so financial security and medical health go hand-in-hand.

“It’s documented that strain or stress from financial issues is a cause of mental health issues,” Riccelli, who chairs the House Health Care and Wellness Committee, said. “We see all of the impacts of poverty, whether you can afford a roof over your head, whether you can put food on the table. Those are huge financial stresses and cause huge mental health issues.”

The Washington Legislature convenes for its first day on Jan. 8. This year, the session is scheduled to last 60 days.