Yellowstone’s backcountry cabins, a link to park’s history, still providing shelter in a storm

BILLINGS – For Yellowstone National Park’s 27 rustic backcountry cabins – the oldest dating back to 1912 – Michael Curtis is the keeper of the keys.

As the backcountry district ranger for Yellowstone, he’s visited all but two of the cabins in his Park Service career.

“I wouldn’t say I have a favorite,” Curtis said when questioned about the cabins. “Each one has its redeemable qualities depending on what you’re doing.”

After a long day in the woods, when you may be cold and wet, as a blizzard or thunderstorm rages outside, it’s hard to beat the comfort of a cabin warmed by a wood stove, he said.

“There’s a lot to be said for that shelter from the storm. It really makes life more bearable.”

Army

The park’s first backcountry cabins were built by U.S. Army soldiers, according to Yellowstone historian Alicia Murphy. The shelters were spaced about a day’s snowshoe or ski trip apart – roughly 12 to 16 miles. The outposts were used by the Army to patrol the park boundary in search of poachers.

These soldiers were nicknamed the “snowshoe cavalry.”

“Several substations were put out in remote parts of the reserve, in which a detail, usually consisting of a Sergeant and two privates, passed the entire winter season, their rations and supplies being taken in during the open season,” E. Hough reported for the Chicago Tribune in an 1894 article. “The life of these men during the long months of snowy solitude could hardly be called enviable.”

Because the shelters were often quickly constructed, many have succumbed to the rigors of the park’s harsh weather and deteriorated, Murphy said.

One of the last cabins built by the Army is not far from West Yellowstone. Army scout Raymond Little helped erect the South Riverside Cabin, about 2 miles from the West Entrance, Murphy said. The Park Service has his records of the work.

Everything from wood stoves to windows and cupboards would be packed in for the structures, Murphy said. Locally sourced stone would sometimes be used for foundations and chimneys.

She referred to the construction as a “product of ingenuity,” with each one built without “hard set rules” and an understanding of whatever would work.

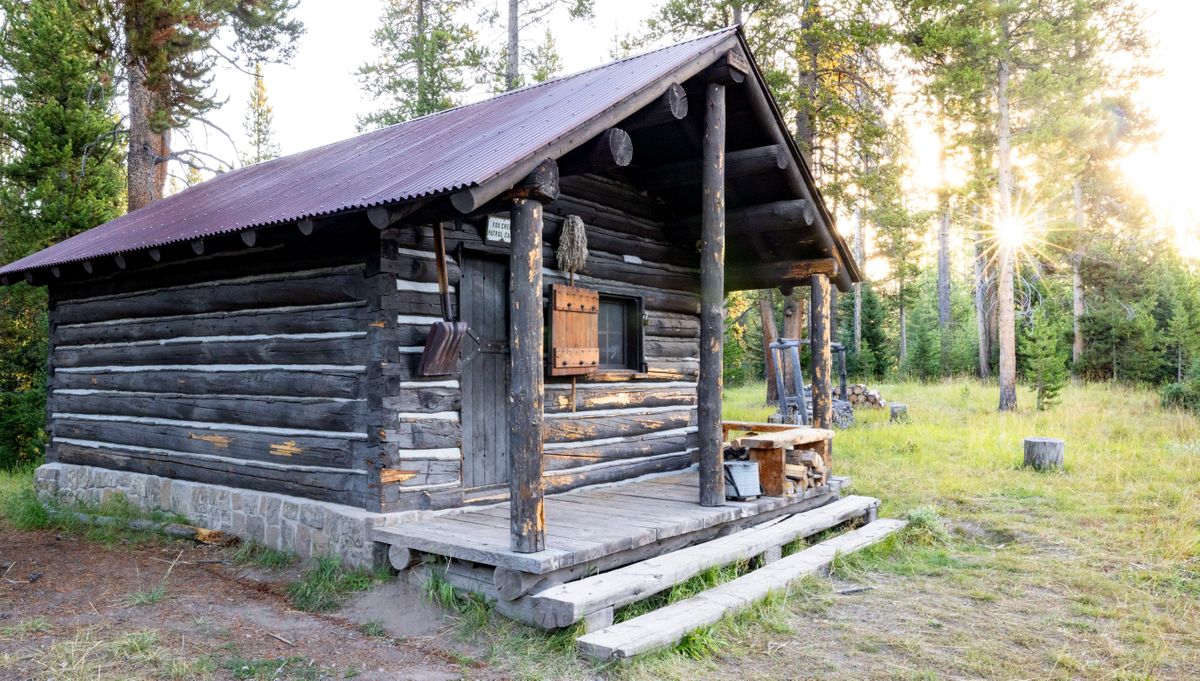

The Fox Creek Cabin, on Yellowstone’s southern boundary, stands apart, as its logs were notched at the ends using dovetail joints, Curtis said. Most others were saddle notched. The inside of the Fox Cabin logs were also hewn down to be flat instead of rounded, a considerable amount of hand work.

Although it is one of the smallest cabins, Curtis said Fox Creek will see as many as 30 nights of use from patrol crews, trail crews and bear management workers.

New rules

When the Park Service was created in 1916, the agency’s leaders recognized the utility of the remote structures and expanded on them.

Harry Trischman, who was a civilian packer for the Army in 1907, and later worked for the Park Service as a carpenter, is credited with building some of the park’s log structures, referred to in his Park County News obituary as snowshoe cabins.

“The backcountry cabins are really a neat part of Yellowstone’s history that people don’t know about,” Murphy said.

Later designs would have been dictated by the Park Service, Murphy said, many of which featured a covered porch extending off the roof.

Between the 1940s and 1960s there was a lull in cabin building, before a few more modern structures were built.

The longest Curtis has been stationed at one of the cabins was three weeks when he was a member of a trail crew. The four to six crew members would sleep in tents outside, using the cabin for cooking, storing food and shelter.

As late as the 1940s, however, he said rangers were posted in some of the cabins in the winter to ensure trappers weren’t crossing into the park. The Thorofare Cabin, deep in the most remote area of the park, has seen park workers stationed there from the end of July to mid-August, followed by a break before returning for the fall hunting season, Curtis said.

Unlike old Forest Service cabins, the Park Service’s are not open to public use.

All of the cabins are stocked with canned food in case someone is facing an emergency, Murphy said. The Park Service has rules for how the structures are required to be left after use. In years past, that included hanging blankets from the rafters to keep them away from mice.

These days, however, Curtis said most of the cabins have been well enough maintained to avoid becoming mouse houses. In a pinch, a visitor can plug a mouse hole with steel wool.

The most modern convenience at some of the cabins is electric lights run off a battery. A solar charger keeps the battery powered up, mainly for radio communication. The lights were an amenity added to reduce the risk of fire from propane or gas lanterns.

“It’s pretty unique to go in and pull a cord or flip a switch and have lights,” Curtis said, especially since users are often arriving in the dark or arising before the sun in the morning.

Old wood-fueled cooking ranges serve a dual purpose of heating the cabins while also providing a place to bake cakes, brownies and cornbread, Curtis said. Propane burners are an alternative to building a fire.

Animals

Although designed for park workers, the cabins also attract animal attention.

“A lot of our cabins are scent posts for bears,” Curtis said. “It’s not uncommon to have bears rubbing while you are in there.”

Bruins will rub up against the logs to leave their scent as a message to other bears. Once, a bear fell through the roof of the Buffalo Plateau Cabin, tearing up the inside of the structure before leaving.

Bears will also sometimes chew on the log structures, Curtis added, as will porcupines.

Although he won’t pick a favorite, Curtis did say the Cold Creek Cabin in the upper Lamar Valley has one of the best views, as does the one at Heart Lake, with Mount Sheridan forming a backdrop to the lake. The Hellroaring Cabin is well-placed to see the migrations of elk and bison back into the park in the spring.

One of the few cabins Murphy has visited, Lower Blacktail Cabin along the Yellowstone River, was destroyed in the history-making 2022 flood. She would like to visit Trail Creek Cabin, at the south end of the Southeast Arm of Yellowstone Lake, but she has to have a work reason to stay there.

“We can’t just use them for recreation,” she said.

To see old photos of the cabins, log on to www.nps.gov/features/yell/slidefile/parkstructures/other/patrolcabins/Page.htm.