Spokane’s growing Spanish Immersion School may get separate building as it seeks more native Spanish speakers

In a Spanish-speaking classroom, first-grader Maisy struggles with a math assignment, though not the Spanish instructions printed on a worksheet.

Kneeling down to ask her questions, Mauricio Segovia deliberately guides her through the equation 5x10 in Spanish, which she comprehends, though she hesitates when he asks how to say the answer in Spanish, preferring the English she’s used all her life. After a couple Cheez-Its and Segovia’s dutiful guidance, she can say the equation in Spanish and spell the answer, “cincuenta.”

“They’re still shy,” Segovia said. “But even with that, we want them to be confident, and that comes with practice.”

It’s a scene that plays out daily at Spokane Public Schools’ ever-growing Spanish Immersion School, where students receive half of their instruction in Spanish.

Freshly hired this year as principal, Segovia has experience teaching in his native country of Chile and overseeing a segment of the Chicago Public Schools. He’s eager to usher in changes at the immersion school to increase Spanish use and integrate more native Spanish speaking students and immigrant families into the choice school. In growing pains, Latino parents are hopeful to be more involved in creating a safe and culturally aware environment.

While supportive of this mission, some school parents say more cultural training and inclusion of Latino advocacy groups is needed following a policy breach in which a uniformed border patrol agent visited a fifth grade class as a guest speaker, unbeknownst to parents or the school’s administration.

The 7-year-old school started with two classes of kindergarteners 25 strong; the school has grown to offer an additional grade of instruction every year since its inception, now kindergarten through sixth grade. The district plans to continue this pattern, housing kindergarten through eighth grade by 2025. Improvements on the Libby Center, a historic former junior high school building that houses Spokane Public Language Immersion and other option schools in the East Central neighborhood are included in the district’s proposed bond that voters will consider in February.

Given the popularity of the unique education model, the district assembled a work group to evaluate the future facility for the school. One prospect is the former Pratt Elementary in East Spokane, though Superintendent Adam Swinyard said he doesn’t have any details finalized yet.

“We’re looking at a long-term facility plan, it’s kind of outgrowing the Libby Center and we actually have an elementary school – Pratt Elementary – that is kind of a stone’s throw from the current Libby,” he said.

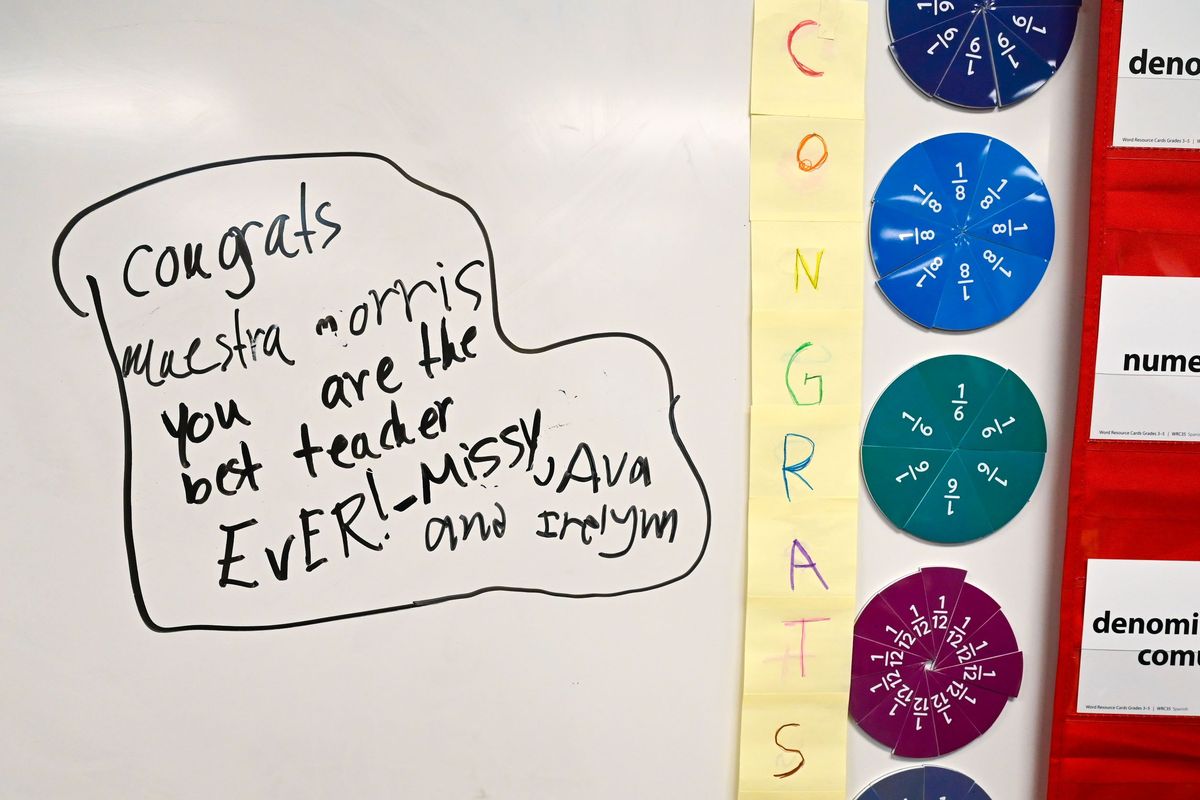

Students split their day between English and Spanish instruction. Jennifer Macias Morris uses Spanish to teach the language and history. Across the hall, colleague Oscar Reviejo Reviejo, originally from Spain, teaches in English language arts and math to the same two cohorts of third graders.

Instruction is 50-50 Spanish-English, though Segovia estimates it’s closer to 25% of a student’s time is spent immersed in the target language. Kids largely use English on the playground and in the hallways. They’ll follow Morris’ instructions in Spanish, but English is their instinctive go-to when asking their teacher a question, to which she prompts “¿En español?”

“You can see, they’re translating it in their head,” she said.

Segovia meanders through the halls of the schools shared by the trio of programs. On the walls are handmade traditional Mexican cutout papel picado on construction paper and strings of paper marigolds, examples of student work and a bulletin board declaring “Nuestros corazones laten en dos idiomas,” “Our hearts beat in two languages.” To his students, he stops and asks “Hola, ¿Como estas?” to which they respond “Bien gracias ¿Y usted?” It’s a call-and-response meaning “How are you?” and “I’m well, thank you. How are you?” that students seem to know by their dual-language beating heart.

In the standard childhood chicken scratch, students write in a sort of Spanish-English hybrid. Unknown Spanish words are swapped with their English counterpart, Spanish words are spelled in their English phonetic. In a worksheet stapled to Morris’ bulletin board, a student wrote their goal for the year is to “Aser la splits,” (to do the splits). Another strives to learn more about animals: “encluding gatos, perros, rabbits y fish,” (including cats, dogs, rabbits and fish).

Segovia envisions a true dual language model for his school, with 80% of instruction and spoken language in Spanish. In Chicago, he oversaw the opening of the first dual language school in the massive district. He aims to hire more Spanish-speaking staff in the shared building and implement a state test for students to be certified as biliterate. He’d also like the option school’s enrollment to better reflect the diversity of the community.

Right now, students enroll via lottery, but Segovia intends to find a different system to integrate more immigrant families and native Spanish speakers – an inclusion with symbiotic benefits to families who may not speak English and English-speaking peers in classes.

“Giving them the opportunity to be inserted in an environment where their presence will be considered a plus rather than a deficit,” Segovia said. “Now imagine yourself being an immigrant in a new place, you’ll start feeling like a deficit.”

Students and families will feel not only empowered, but celebrated by speaking their native tongue, a stark contrast from Morris’ grade school education. Her parents emigrated from Mexico as teenagers before she was born in California.

“I remember just having to do (English as a second language ) classes, having to be taken out and just feeling different,” Morris said. “But I think if I would have had this growing up, I think it would have been a different schooling experience for me and my parents, too, because they didn’t know how to help.” Morris said.

In turn, kids from English-speaking families will improve their Spanish and cultural understanding by the exposure to their Spanish-speaking peers, recognized for their expertise in the language rather than admonished for lacking in English.

“It’s just getting them to feel more comfortable, like ‘Oh there’s a school that speaks my native language’ instead of being scared,” Morris said. “We’re going to learn from you and we’re going to learn together.”

Recent events at the school in which a teacher invited a parent and U.S. Border Patrol agent to speak at the school raised some red flags for some school parents including Jennyfer Mesa, executive director at Latinos en Spokane.

Pia Johnson Barreto was still reeling a week after her fifth-grade daughter came home from school with U.S. Customs and Border Protection-branded merchandise, given to her by the Border Patrol agent and school parent who spoke in her class. Barreto emigrated from Peru and had instilled in her daughter a wariness of Border Patrol agents; the presence of an officer at the head of her classroom in uniform – badges, patches, vest and gun – filled her with anxiety, Barreto said.

Content presented to students was contrary to what Barreto teaches her kids and what they’ve witnessed in their community. Though she’s a citizen, she said she is cautious of Border Patrol agents and the distress their presence and enforcement inflicts on the Latino community: family separation, raids and racial profiling.

“The messaging we have shared with our children is that we don’t let Border Patrol in the door, that we are cautious about their presence,” Barreto said, “We’re also protective of other members in our community that are undocumented and could experience harm.”

At a Spanish language school, Barreto thinks it’s important to teach students about immigrants and refugees, but she wishes these groups were more involved in the conversation.

“Think about the experience of having someone else tell you about who you are,” Barreto said. “How painful is that for young people to hear?”

Mesa’s daughter attends the school and she said the agent’s presence was “insulting” and brewed a sense of unsafety among students, her daughter included, though she wasn’t in the class where the agent spoke.

“It’s just it’s so tone deaf, to the lived experiences about immigrants, and there’s a disconnect where you can’t only teach the language and the fun parts of a culture and exclude all the other realities and histories,” Mesa said.

“Out here in Spokane and Eastern Washington, our deep history is tied with racial profiling, separation of families, ICE raids, and that is still happening today,” Mesa said, referring to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Segovia said in a letter to families that he wasn’t aware of the guest speaker, which goes against district procedure that says the principal has full responsibility for speakers. In the letter, he wrote he plans to ensure more oversight and that procedure is followed.

School Board President Nikki Lockwood acknowledged the cultural complexities of the situation, and said the district responded quickly to affected families and addressed the procedural failing. She’s supportive of the unique education provided by the school and all the “good work” staff is doing in advancing the program.

“We want all our kids to feel safe and they all they all deserve to feel safe,” she said. “And this is not about that individual officer. This is more about the impacts of Border Patrol as a whole.”

Mesa said she’s been happy to watch her native Spanish-speaking daughter grow up with a pride in her language, but she said the few native speakers in the school are expected to speak up and participate more than their hesitant counterparts. She said she would like to see more Spanish-speaking students, but first, staff needs more culture awareness training.

A diversity, equity and inclusion consultant, Barreto is supportive of the school and its endeavors. She said she “wholeheartedly adores” her daughter’s teachers and can tell they’re trying to provide the best for their pupils. She was excited to have her daughter exposed to her native language and wants more inclusion of Latino culture in school curriculum, though in such a way that is inclusive and fosters belonging in vulnerable groups.

“You’re not alone in this process,” Barreto said. “We have a community of immigrants and refugees that really want to be a part of the wellness of our youth, so more opportunities to be a part of that would be wonderful.”