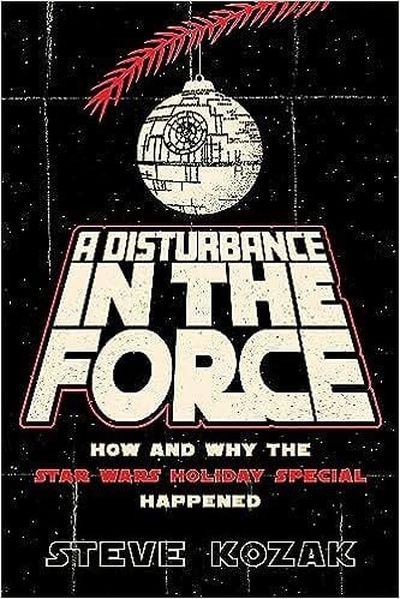

‘A Disturbance in the Force’ book contains variety show gems from an insider

When I first saw a book about the making of the “Star Wars Holiday Special” for network television in 1978, my first reaction was, “Why?”

I was graduating high school in the Missouri Ozarks when “Star Wars” premiered in San Francisco, really a galaxy far, far away from my little town, which was not one of the 32 theaters to get the initial release. But we heard about it, and by the time it did come to town it came with an immense force surrounding it. Still, despite being in the midst of “Star Wars” mania, I do not remember the holiday special.

When I asked some other friends my age, they did not remember it either. It was that forgettable. So why would anyone write a book about something so few people remember? Those who do, including George Lucas, would like to forget.

Then I started reading Steve Kozak’s fascinating book, “A Disturbance in the Force,” and was engulfed in the universe of kitsch TV, the kind that was a part of my growing up.

Kozak pulled a big switch. While yes, the book is about that debacle of a holiday show, it’s also a deep dive into television in the days before cable and streaming – long, long ago when there were only three channels, maybe four if you count PBS – and you had to get up and walk across the room to change those channels.

Kozak is uniquely qualified to write such a book. He grew up with his dad, who worked for Bob Hope, the legendary radio and movie star from the 1940s and ’50s who conquered television in the 1960s and continued to produce network shows way past his prime. Kozak lived those days when news, sitcoms and drama were sandwiched between what were then known as variety show TV.

Those shows featured a star of the day, maybe only a minor celebrity at that, in a show of sketch comedy, songs and dance numbers that hearkened back to the days of live vaudeville. It played to a generation of Depression-era kids that remembered vaudeville and was stuck at home taking care of large families of kids known as the Baby Boomers. My mom would never miss the “Andy Williams Show” and we kids watched Ed Sullivan introduce acts like Elvis Presley and the Beatles to America.

By the 1970s, the variety show was in full force, with Glen Campbell giving way to Sonny and Cher, Donnie and Marie Osmond, and Tony Orlando and Dawn.

These shows were ratings hits and created their own musical hits, as people would rush out to buy records of songs we heard on those shows. It was topical comedy and pop music hits in shows that weren’t meant to last.

As Kozak points out, it was disposable TV.

That is the environment in which George Lucas agreed to the “Star Wars Holiday Special.” Or that is the romanticized milieu. Those top shows by 1978 had been replaced by variety programs hosted by mimes Shields and Yarnell, Mac Davis and “The Brady Bunch Hour,” a musical program starring the cast of the family sitcom that had been canceled years before.

It wasn’t a pretty time. As Kozak describes it, “ ‘The Brady Bunch Hour’ wound up being about an hour too long.”

Still, there were television gems left on the screen, such as a Christmas duet between crooner Bing Crosby and rocker David Bowie, right before Crosby’s death, that became legend. The same production team that came up with that piece of gold oversaw producing the “Star Wars Holiday Special,” which would not have the Force with it.

Kozak also introduces us to Charles Lippencott, a film school classmate of Lucas at the University of Southern California, who was more interested in marketing and publicizing films than making them. Kozak points out that Lippencott is left out of most “Star Wars” histories and behind-the-scenes stories. Yet it was Lippencott who pioneered some of the key moves in making “Star Wars” a blockbuster, some of which have become standard marketing practices in today’s business.

Lippencott knew “Star Wars” would create its buzz by word of mouth, but that meant getting people to early showings. A comic book fan, Lippencott started marketing the movie through the fledging comic book conventions, known as ComiCons.

He produced the novelized version of the movie in book form before the movie was released. And he was kicked out of a toy convention for trying to sell “Star Wars” action figures, an idea turned down by Mattel and other major manufacturers, only drawing the interest of Kenner, which made toys like the Easy Bake Oven and wanted to test the growing action figure market.

It was a wild time, when the movie business was just figuring out what we know sees as business as usual.

While Kozak does tell the masterful story of how the holiday special made it to the airwaves, it’s the context he puts it in with the insider’s television history that makes this book such a find.

If you’re a “Star Wars” fan from way back, you’ll find plenty of stories to love. If you’re the kind of person who collects “Star Wars” and goes to conventions, you’ll find some details you probably didn’t know.

But even if you couldn’t care less about “Star Wars” or this 1978 special, you’ll find fascinating history about a colorful time long, long ago, and culturally far, far away.

You’ll never again look at television the same.