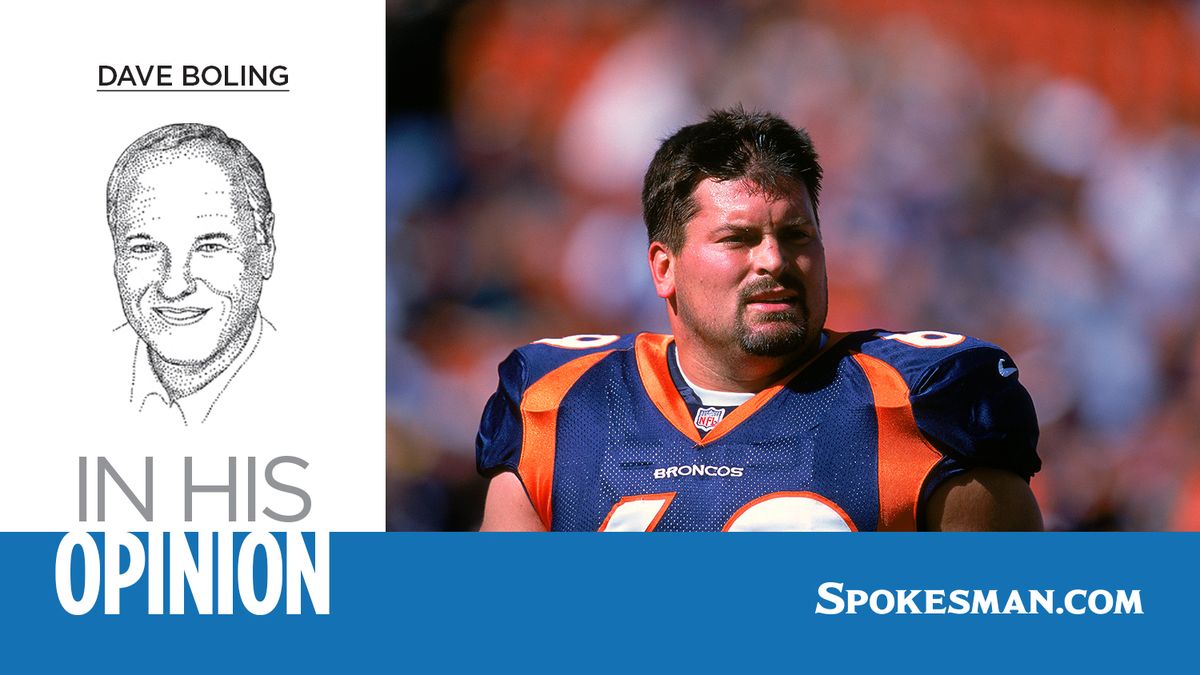

Dave Boling: Former Idaho standout Mark Schlereth still pulling more than his weight in broadcast booth

Doing research for an upcoming broadcast of the Seahawks’ last preseason game, Mark Schlereth made a request unique for a network television commentator visiting the team’s headquarters in Renton, Wash.

He asked if he could use the team’s weight room. He was in town to gather inside information, but it was a Monday, and Monday is one of his heavy lifting days.

Even at 57, he spent an hour or so in there, moving iron with the ferocity of a powerful young NFL lineman.

Asked for some of his weight-room maxes, he said: “You know the 225 (pounds) they use for the bench press at the combine? I guarantee you I can do 40.”

Last spring’s leader at the NFL combine powered out 38 reps. The best the year before was 29.

Impressive lifting exploits for a member of the media, to be sure, especially since Schlereth is more than twice the age of the draft prospects, and also since it’s remarkable that he’s even somewhat ambulatory, his NFL career having finally ended with his 29th surgery – 20 on his knees.

Seemingly bionic strength is just one way in which Schlereth has been a unique outlier: He was the first Alaska native in the NFL, and a 10th-round draft pick out of Idaho who ended up starting on three Super Bowl-winning teams.

The man had been such an orthopedic nightmare that he first retired from the game as a junior in college but willed himself through a subsequent 12-year NFL career.

In a series of improbable achievements leading to unexpected opportunities, his one constant has been football. Incisively, he self-identified on his twitter.com account (which has more than half a million followers): “Football guy.”

“Since I was 12, the only thing I ever wanted to be was a football player.”

•••

Schlereth’s coach at the University of Idaho, Keith Gilbertson, with the concern of a kindly uncle, advised Schlereth to retire from football. The skin of Schlereth’s knees was already embroidered from six surgical interventions, and his elbow required serious rebuilding.

So Schlereth retired – for a couple months. He returned in the fall and played well enough to be drafted by Washington’s NFL team, now known as the Commanders. Halfway through his rookie year, he was starting at right guard .

“I made a promise to myself when I came out of Idaho that if I didn’t make it, it was going to be because I just wasn’t good enough,” he said. “It wasn’t going to be because I didn’t work hard enough or study hard enough or prepare enough.”

Through six years with Washington and six more in Denver, Schlereth pocketed three Super Bowl rings and two Pro Bowl honors.

One-hundred percent of the time, he said, he faced defenders who were better athletes than he was. His secret was maximizing his strengths and minimizing his disadvantages through preparation.

“I never missed a meeting, never missed a (lifting session), was never unprepared. When I walked away after 12 years, when my body failed me, I knew there was not one ounce more work I could have done.”

In his six seasons in Denver, he only missed three assignments. “I had to study the defense to where I could anticipate what’s coming. I could never take a false step. Now, I wouldn’t always get the guy blocked, but I always knew my assignment.”

•••

Telling Schlereth’s story requires a public-service disclaimer: Contact sports can result in injuries. Ignoring sound medical counsel is inadvisable.

The common suggestion is that injured persons should “listen to their body.”

Schlereth tells his body to shut the hell up.

“I’ve been in pain since I was 17 or 18, with my first major knee injury, so that’s all I’ve known,” he said. “I could always make myself do things that, physically, shouldn’t be possible.”

He supplies examples but only upon request.

One Sunday in 1995, an attack of kidney stones – a famously excruciating malady – landed him in the hospital. Unable to pass the stones all day, he was wheeled into surgery at 11 p.m. to have them cut out. He checked himself out the next morning, drove to Mile High Stadium and started the Monday Night Football game against the Raiders.

“I did a lot of stupid things, but it was important to me,” he said. “That was a badge of honor for me. It’s just the way I was wired.”

•••

Forced into retirement after the 2000 season, he planned on doing nothing but resting and healing for two years.

“Two weeks into retirement, my wife said, ‘Dude, you gotta find something to do’.”

Soon after her declaration, Schlereth got a call from HBO Real Sports, doing a segment on the toll football takes on a player’s body.

“It went great, and after they showed the segment, (reporter) Jim Lampley sits down with (host) Bryant Gumbel for some follow-up questions,” Schlereth said. “Bryant asked what Jim thought I would do next. Jim said, ‘I don’t know, but whatever it is, he should get in the media because that dude is entertaining.’ ”

The morning after the show aired, agents were on the phone wanting to represent him. Two days later, he was on a plane for an audition with ESPN. He was hired on the spot.

Sixteen years with ESPN led to his color-commentary of games for Fox, a full-time radio show in Denver and a popular sports podcast. A little soap-opera acting and partnering in a company that produces chili sauce were side gigs to his main diet of football.

On air, Schlereth exercises a strong point of view in an authoritative voice. It often spurs debate. Like the iconic John Madden, Schlereth brings a lineman’s perspective to the broadcasts. Where Madden entertainingly captured the sounds of the collisions, Schlereth finds ways to share with viewers how it feels to be in the vortex of violent action.

•••

As old teammates will do, Schlereth and John Pleas (a Vandal safety and punter from Spokane) were busting on each other on the sidelines before a recent Seahawks training camp practice. Pleas, the Seahawks senior director of corporate partnerships, recalled Schlereth’s career at Idaho.

“He was the consummate locker room guy, always friendly, always keeping things light, telling stories and jokes,” Pleas said. “And he had the respect of everybody on the team because of how hard he worked and played on the field. He is still totally beloved.”

“They’re still my closest friends in the world – the guys I played college football with,” Schlereth said. “That experience was awesome, playing for each other, the love we had for each other.

•••

Schlereth’s interviews are rapid-fire, and he riffs theories and opinions and stories from the field.

But he paused for thought before answering the question of which achievement brings him the most pride.

“Most proud of? Always being there for my kids,” he said. “You make choices in your life and I made the choice to be there for every event; I coached every baseball team, every soccer team. My wife and I never outsourced the raising of our kids to somebody else.”

He remains, though, a fully focused Football Guy.

“I would have preferred not being hurt as much, but I can honestly sit here and tell you there are zero regrets. It’s all worked out.”

With a deep pull of a quote from the ’ 80s band, The Alarm, Schlereth found the ultimate way to describe his relationship with football:

“It’s the life’s blood that courses through my veins.”