Summer Stories: The Callback: Black Butterfly

By April Rivers Eberhardt

On a brisk February morning, I attempted a morning workout on the treadmill. In routine fashion, I turned on my cellphone to get my music ready when a deluge of Facebook notifications poured onto my screen. I was being summoned to call home.

“It’s your mother.”

Grief has no formula. It is a steep hill; an airless vacuum; a sucker punch. It scribbles outside of the lines, sneaking up on you at the grocery store, creeping into a song on your playlist. It makes you sad, happy, angry, withdrawn, and we all look for that moment of acceptance. You start to ask yourself questions about the deceased. Maybe you will have a conversation with them. Maybe you will obsess over what they were thinking when they took their last breath. Maybe you will reimagine their last moments with you by their side. Maybe you will try to call them on the phone out of habit only to realize that the number is no longer in service. You want to know if they are OK. You want to comfort them. You want to say the things you regret not saying and you fantasize about future times you would spend with them in companionship that will never come to pass.

In an act of unpredictability, death stole my mother from me. I was left on this side of time with unfinished business and loose ends; unspoken apologies and unheard forgiveness lingered. I was not ready. When I got the confirmation of her passing, I lost strength in my limbs and fell to the floor. Just two nights before, I had suddenly awakened with the urge to call her at 4 a.m. She did not answer, so I left a message: “Mommy, I am just calling to check on you. Haven’t talked to you in a while. Call me when you get this. Love you.”

The connection we had was now rotting in the stages of post-mortem decomposition, and the phantom of grief harassed me. That random call was my last lifeline to her, and I hadn’t even known it. Now I desperately wished for one last interaction, but it was too late.

A fluorescent orange coroner’s notice greeted me at my mother’s apartment door when I arrived to clear out her belongings. Since I lived in another country and was her only legal next of kin, nothing could be done until I got home. The notice had been stuck there for several weeks. Neighbors I didn’t know gave me their condolences as I went into her place to see the remnants of her last days alive. The television was still on and her answering machine was blinking when I walked into her bedroom. I hit play. After a few messages, I heard my own voice. My intuition told me that the 4 a.m. call had not been an accident; she had heard my voice before transitioning; there was no other way that I could see it. The gaping hole of her physical absence from this world agitated me like a dropped call in a cellular dead zone. She had died in that apartment alone. Tears welled.

“Mommy, call me back.”

“Mommy, people really don’t come back from the dead, right?” I asked this question when I was about 8 years old to fact-check something that my great-grandmother told me countless times throughout my childhood. In general, ghosts were taboo in my own family narrative, except for when my Gram would use them to scare me out of sucking my thumb when I was a pesky kid sitting under her tutelage in the hot kitchen on Atwell Street.

Growing up, I would hear smatterings of conversations about haints, spirits of the dead who would, allegedly, come back to haunt the living. Haints were spooky beings with ill intentions in lore passed down by Black Americans throughout different parts of the South for generations. Superstitions like painting shutters, porch ceilings, and front doors “haint blue” to create an illusion of sky or water that would trick these specters into passing right through, were said to deter spirits from entering homes of the living through open doors or windows. Then there was the bottle tree; fastidiously tying glass bottles (especially blue glass) from trees on strings or sticking them onto branches was supposed to trap unwelcomed haints. There was also the tale that wearing dimes in your shoes at someone’s funeral would ward off evil spirits. I first heard the term haint spoken by my great uncle Elijah as a child.

Despite this, my Gram, a hilariously blunt woman from Georgia, creatively tried to dissuade me from being the avid thumb-sucker that I was by using the myth of the boo-hag; haints that would come at night to get disobedient children. I would hide just to not hear her shout, “Take ya’ fanga’ outcha mouth!” With her Southern sarcasm and country inflections, she would admonish me about how my teeth would turn out; at one point, she and my grandaddy even taped quarters to my thumb. Nothing worked; I did it anyway.

To emphasize her disapproval of my thumb-sucking, Gram would caution that if I did not stop, she would come and sit at the foot of my bed when she died to haunt me until I did. More humorous than scary, I just whimsically followed the logic, as I did with so many other strange iterations of cause-and-effect heard in her house. Ghosts were too close to demons and nobody that I know wants to tangle with Satan’s henchmen.

I knew by middle school that the paranormal was not my thing, thanks to a girl named Regan whose head turned 360 degrees and whose voice, in its low register, evoked something sinister. Now, “Scooby Doo” is still one of my favorite cartoons; I grew a love for mysteries watching Fred, Velma, Daphne, Shaggy and all their ghoul and goblin escapades, so I will stay in my safe zone when it comes to ghosts – right there in the land of make-believe.

My grandmother, who I called Ma, always came to my defense against her mother, my Gram. Ma would chide Gram to stop telling me such tales and would correlate my thumb-sucking to it filling a void or being a type of coping mechanism, because of a news article she had read in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. She guaranteed that I would be just fine in the long run, because she herself had been a thumb-sucker and had turned out OK. I felt both vindicated and indulged by this repeated debate that would play on a loop throughout different episodes of my upbringing.

Of course, my own mom would just tell me that “there are no such things as ghosts” and “you can’t believe everything you hear” or “don’t believe everything you see on TV” when I would fact-check these strange iterations of logic with her.

I can definitively say that my great-grandmother never came back as a haint to scare me; I officially stopped sucking my thumb by the time she passed away, but for all those years of disobeying her, she hasn’t made it to the foot of my bed. Though I do wonder if my needing braces at 46 years old is her way of telling me “I told you to stop now didn’t I?”

Gram, Ma and my Mommy have now become ancestors.

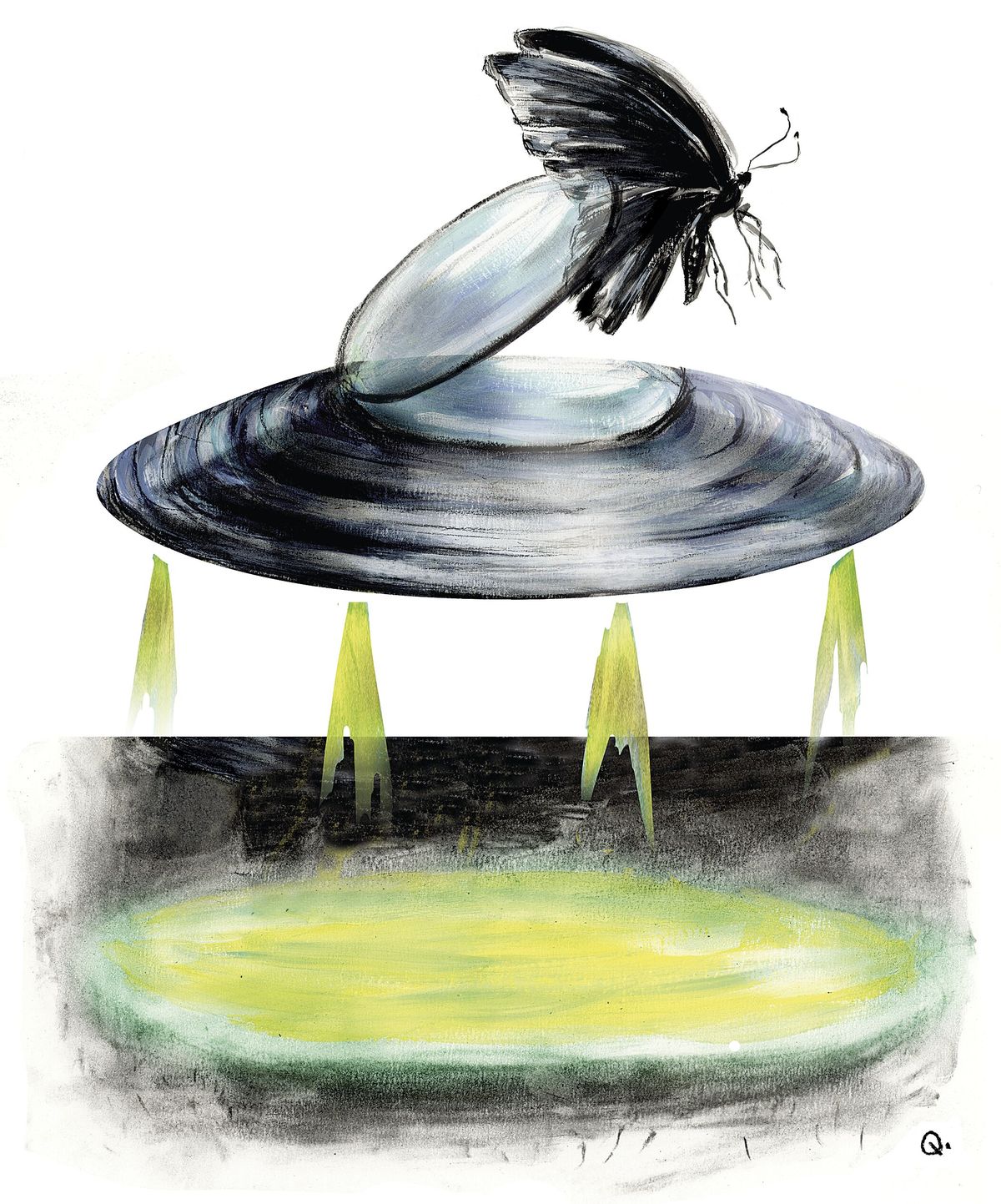

A pilot-less spaceship from another world came to get me. It descended on the roof of my house; a ramp was extended, and I walked onto the vessel as if I was boarding Port Authority transit, not at all surprised by its arrival. I was quickly transported to a familiar place in a neighboring world. The spacecraft hovered over the fire escape of an apartment building. I climbed down the ramp, hopped onto the stairwell, and saw a half-raised window leading to a kitchen. Peering in, I pushed the window up farther, put one leg in and found my way to my mother who was waiting for me. There she stood, despondent with an expression of impending sadness. The disquieting feeling of unpreparedness and trepidation badgered us both as we somberly greeted each other and embraced the inevitable. I grabbed her hands. She told me that she was ill and was not going to be here much longer; her time had come. I became deflated and just stared, soaking her up for the last time, and mustering the courage and strength to accept what was now beyond my power or control.

Decidedly in that second, I was going to share this final, tender moment with her in true mother-daughter fashion, like the days of my youth when I would sit at her knees, in her bedroom while she untangled my thick hair.

This last bonding ceremony was our refuge. In this instance, the roles became reversed. Vulnerable and weak, she now sat at my knees. Not much dialogue occurred between us, just a silent understanding. I massaged her scalp and brushed through her locks, creating parts and sections with the comb. She sighed and I cried. I cried and she sighed. Together we mourned, in catharsis. I told her not to worry, that everything was going to be OK and that I would always love her. I hugged her tightly one last time. Putting one leg out of the window, I climbed out to the fire escape, and boarded the spacecraft. I did not say goodbye. Unconditional love enveloped us both. She had called me back.

The spaceship then took me to visit Ma, who had been besieged by Alzheimer’s disease for the past 20 years. The last time I had seen her, her gaze was hollow as she studied my face, trying to make a connection. During this visit, she had a look of certainty and recognition that I had not seen since this cruel takeover. She spryly greeted me, “Well hello, Little Lady.” I had not heard this nickname since I was a kid. Gesturing to look at the dresser, with a steady alto drawl, she said, “Look there, for the hair ribbons ya’ mama left. They’ll go nice with ya’ outfit.” Hair ribbons? Outfit? Then she beckoned me to get ready for “the service.” I was so confused. She then pointed to a pair of worn shoes tucked in the corner of the room. She motioned for me to come sit down next to her. These words she spoke: “When there are many births, there are also many burials, but the future emerges from the past. See those shoes over there? Don’t forget to walk the path. The journey is ours. Now go on and get ready. We waitin’ on ya’.” She patted me on the arm and sent me on my way.

On the return flight, trombones and trumpets played at high tempo. The cadence of drumbeats and clapping hands palpitated in melodic crescendos and modulations. Tambourines jingled. Bright, warm light filled the vessel as I journeyed back to my side of time. A Black Butterfly perched itself on a window ledge in the spacecraft. When I spotted it, I heard the words “keep going.”

A year after my mother died suddenly, Ma passed away. Like deja vu, I returned to prepare for her homegoing service, crying harder than I had the year prior. We buried my mother’s ashes with Ma. I sorrowed over the end of an era. But then, I recalled the spaceship dream and remembered the Black Butterfly. Bequeathing its spirit and imparting ancestral wisdom on those of us still on the journey, the Black Butterfly speaks the timeless message of transformation, inheritance and rebirth. Endings become beginnings, darkness turns into dawn, life is both a circle and a cycle.

It appears in the regeneration of my Gram’s apple dumplings by memory because she never wrote anything down. It is the renaming of nieces and nephews after their great aunts and uncles; it is recycling the surnames of grandparents into the middle names of their children’s children. It appears when the rationale of old admonishments and chastisements become understood in adult maturity. Its power is sung in the elegy by Deniece Williams:

“Black Butterfly, sail across the waters, tell your sons and daughters what the struggle brings. Black Butterfly, set the skies on fire, rise up even higher so the ageless winds of time can catch your wings … let the current lift your heart and send it soaring, write your timeless message clear across the sky, so that all of us can read it and remember when we need it, that a dream conceived in truth can never die, butterfly.”