Process to review offensive landmarks, street names in Spokane vetoed by Woodward

A recently created process to review potentially offensive landmarks and street names found on city property, spurred by concerns over the downtown statue of Ensign John Monaghan, has been vetoed by Mayor Nadine Woodward, who argued the City Council empowered the wrong citizen commission to oversee the process.

It’s exceedingly unlikely that the veto will be overridden, as the City Council is down one member of the liberal supermajority it had when the ordinance was passed. Once vetoed, the ordinance cannot be resurrected as originally written.

Woodward’s July 24 veto letter was the first that the City Council heard of the mayor’s concerns, four council members told The Spokesman-Review. The Spokane Human Rights Commission, which Woodward objected to having a lead role in the review of offensive city-owned property, also wasn’t informed, Chair Anwar Peace said.

Someone should have asked, the administration said Thursday.

“I’m not aware if the administration was ever asked or an effort for the administration to be involved in the process,” said Brian Coddington, city spokesman and the mayor’s chief of staff. “This seems like an opportunity to be better all-around at including the administration in conversations about ordinance development.”

Almost every veto Woodward has issued during her term has been overridden, which requires five votes from council members. But the ordinance passed 5-2 in early July, and one of the council members in favor, former Council President Breean Beggs, has since left, with a seat vacant.

The empty seat won’t be filled until Aug. 28, but the council has until Aug. 24 to override the veto, meaning the ordinance is almost certainly dead. Councilman Jonathan Bingle, who voted against the ordinance originally, is on paternity leave until Labor Day, according to Council President Lori Kinnear. The other no vote came from Councilman Michael Cathcart, who said Thursday he has no plans to change his position, arguing that creating a process to remove statues is the first step on a path that ends in banning books.

“This was very sneaky by the administration,” Peace said in an interview. “Two years of work, blood, sweat and tears have gone into this, and for this to go down this way is very disturbing.”

The ordinance could not have been vetoed while the council’s left-leaning supermajority remained, however, as it was passed July 10, during Beggs’ last day on the dais.

The ordinance broadly allowed residents to request reconsideration of imagery or place names deemed offensive.

The Spokane Human Rights Commission would have been the ones receiving the request and making an initial determination if the landmark or place name was “likely to cause mental pain, suffering or disrespect in a reasonable person …” If so, the commission would have kicked the issue to the Office of Civil Rights, Equity and Inclusion, which would review the request in consultation with city legal, other city organizations and relevant stakeholders.

The office would then present its findings back to the commission, which would have made a recommendation to the City Council, the Park Board or the Library Board, depending on the location of the offensive monument or street name. One of those three bodies would have final say in whether to remove, rename, relocate or otherwise take action on the matter.

The two-year saga that culminated in this process being created began with the Human Rights Commission, Peace said, when members of the city’s Pacific Islander community requested removal of the Monaghan statue.

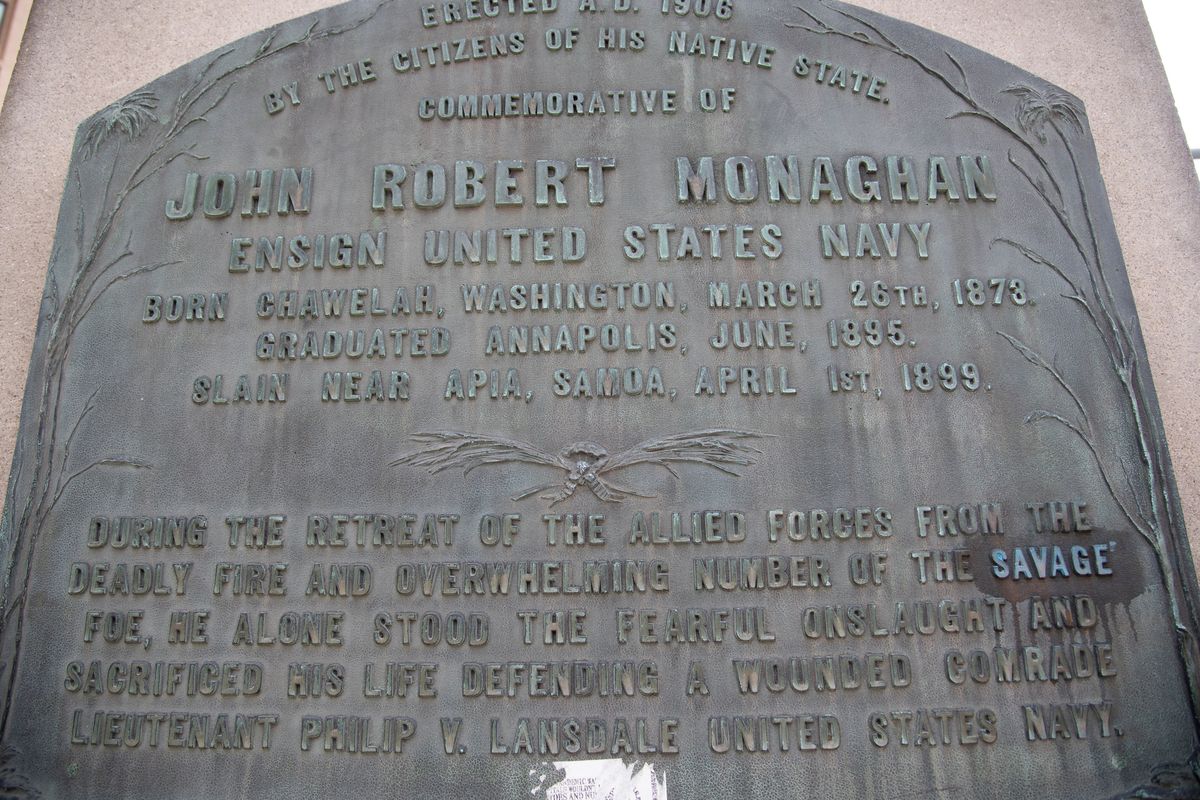

Monaghan was a U.S. Navy ensign from Spokane who was killed near Apia, Samoa, during the United States’ effort to colonize the country in 1899. The statue, which the city does not own but is located on city property, was commissioned by residents in 1906.

One plaque on the statue describes the Samoans who killed Monaghan as “savage foes,” while another shows those Samoans as wielding primitive weapons, which Peace called inaccurate and racist. The Spokane Council of the Navy League of the United States has argued that aspects of the Monaghan memorial should be updated, but that the statue should remain because Monahan acted heroically to protect a fellow sailor in battle.

When the Human Rights Commission reviewed requests to remove the statue, it was determined that the city had no formal process to address such concerns, Peace added. The City Council asked the Human Rights Commission to develop such a process, an effort Peace led.

Woodward, in her veto letter, said the Historic Landmarks Commission should be in charge of reviewing concerns from residents, not the Human Rights Commission.

But Peace said the Landmarks Commission had already said it is not the proper organization to review such requests, as it can only review proposals to modify, move or demolish property on the historic register. The Monaghan statue is not on that register.

“They affirmed they wanted nothing to do with it,” Peace said. “If you want to create a historical district, that’s the Landmarks Commission you want to go to. But if you want to deal with race, equity, that’s the Human Rights Commission.”

Alex Gibilisco, the City Council’s manager of equity and inclusion initiatives who helped draft the now-vetoed ordinance, confirmed that the Landmarks Commission had indicated such review was outside of its jurisdiction. Historic Preservation Officer Megan Duvall, the city liaison for the Landmarks Commission, did not respond to a request for comment.

Woodward argued in her veto, if the Landmarks Commission is not designed to process such requests, the City Council should modify its duties, rather than hand the responsibility to the Human Rights Commission.

“You’re going to have the commissions colliding if one is reviewing for historic preservation purposes versus another for human rights purposes,” Coddington said Thursday. “Why not deal with these through a common body?”

This is the eighth veto of a City Council ordinance since Woodward took office, and only the second not to be overridden by a supermajority on the Council, according to a list kept by the city clerk.

The first was an ordinance passed last September that would have created more oversight for how the police use money from civil asset forfeiture – a controversial practice of seizing money or property allegedly involved in a crime or illegal enterprise – and dedicated some of those funds for youth drug prevention services.

That ordinance only had the support of four council members, as Councilwoman Karen Stratton joined Bingle and Cathcart in opposition, meaning it lacked the five votes needed to override Woodward’s veto.