Navy divers comb a Pacific graveyard, seeking lost World War II airmen

The diving bell, left, and habitat, right, for the mission, as seen in September in Panama City, Fla. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post photo by Michael E. Ruane (Michael E. Ruane/The Washington Post)

The bomber’s pilot, 1st Lt. Herbert G. Tennyson, a former hotel clerk from Wichita, Kansas, approached the target at an altitude of about 8,000 feet.

His B-24 carried eight bombs, an array of heavy machine guns, and 10 other men.

Tennyson was 24. He’d been married for 10 months. His wife, Jean, his high school sweetheart, was seven months pregnant back in the states.

Painted on the nose of his plane was a racy image of a woman with angels wings, and the nickname “Heaven Can Wait.”

As the aircraft approached the Japanese target at Awar Point on the Pacific island of New Guinea on March 11, 1944, it was hit by antiaircraft fire. The tail broke off, and the plane plunged into nearby Hansa Bay.

Three figures were seen jumping out as it went down. The wreckage burned on the surface and sank in about 200 feet of water, leaving behind a large oil slick. There were no survivors.

Earlier this month, a team of elite Navy divers and archaeologists from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) ended a five-week, deep-water search of Hansa Bay for the bones of Heaven Can Wait’s crew.

The project unfolded about 10 miles from an active, 6,000-foot volcano in one part of World War II’s vast Pacific Ocean graveyard. It was the deepest underwater recovery mission for the DPAA, the government agency that seeks to account for service members missing in action from past wars.

And it was the first time the Navy’s so-called SAT FADS – Saturation Fly-Away Diving System – had been used in such a role, the Navy said.

The DPAA said “osseous” material that could be bone had been found, as well as “material evidence that could be used to support any potential identifications,” and two aircraft machine gun barrels.

The agency said the osseous material was being treated with the reverence and ceremony due human remains, but verification would need to take place in the DPAA laboratory at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii.

The wreckage of the plane had been discovered in 2017 during an underwater survey by Project Recover, a nonprofit partnership that uses technology to hunt for the missing, mainly from World War II.

Project Recover located the bomber using data from a detailed, four-year investigation by relatives of one member of the crew, 2nd Lt. Thomas V. Kelly Jr., the plane’s bombardier.

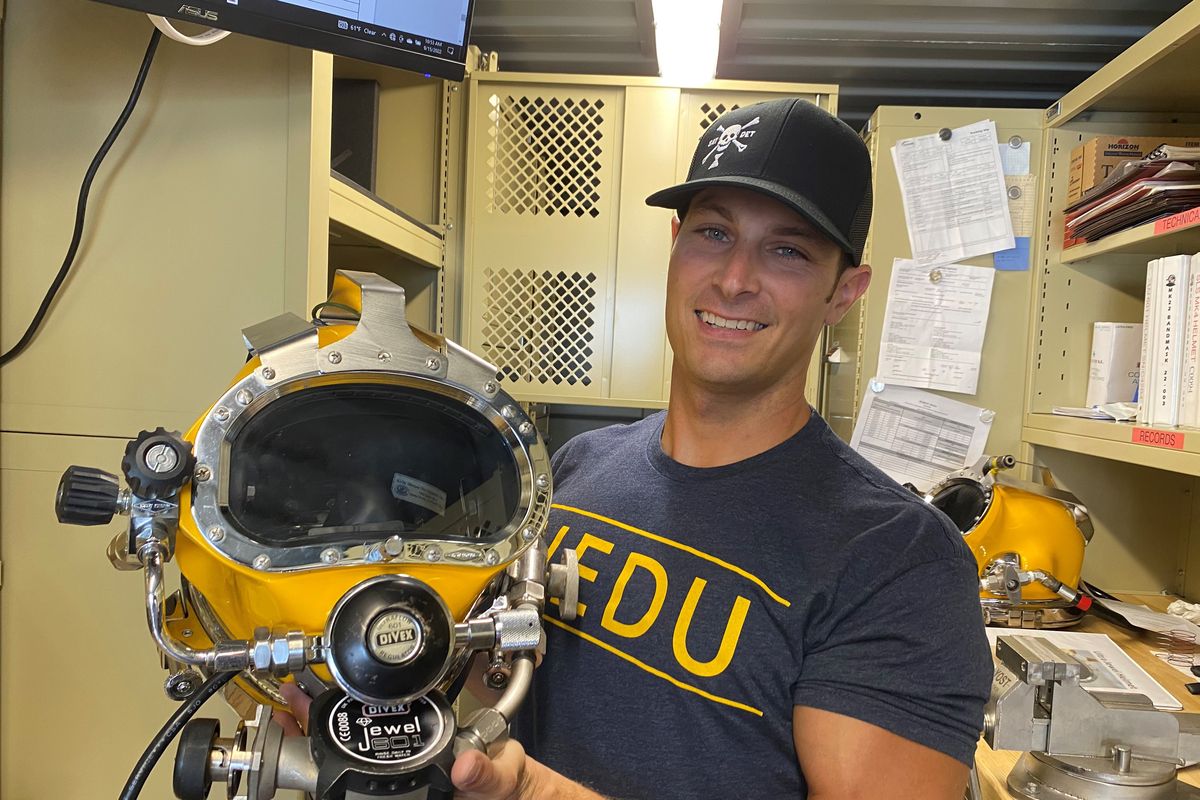

In early March, a vessel carrying the diving system, divers from the Navy Experimental Diving Unit, and experts from the DPAA arrived in Hansa Bay, the DPAA said.

The diving apparatus, somewhat like a space station, included a pressurized habitat where the divers lived aboard the ship, and a pressurized diving bell, which they used to reach the bottom.

The system allowed them to work in the pressure of deep water for long periods without having to decompress after each dive, the Navy said. They only needed to decompress at the end of the project.

Once on the bottom, the divers exited the diving bell and vacuumed material from the crash site into big baskets that were hauled up to the ship to be sifted for artifacts.

“Remains do survive … even after 80 years of being on the sea floor,” said Katrina L. Bunyard, a DPAA underwater archaeologist and historian.

Andrew Pietruszka, Project Recover’s lead archaeologist, said, “Fish and other animals and microorganisms, they’ll eat all the soft tissue” but leave the bones. “That’s why we get, typically, decent preservation.”

Tennyson’s grandson, Scott Jefferson, 52, of Queenstown, New Zealand, said he thought the plane’s loss “was a mystery that would never be solved. … I’m just overwhelmingly grateful to everybody that made this happen.

“Throughout my childhood, I just visualized they must have gone down in the middle of the ocean, in the middle of nowhere … and that was that.

“My grandma, even when she was more than 90 years old … it was a really hard subject for her. She never remarried and … never gave up hope that he was coming home.”

The wreckage of the plane was found scattered across the bottom of the remote bay off the Bismarck Sea in the southwestern Pacific Ocean.

The experts had pinpointed the front section, where Tennyson; co-pilot Michael J. McFadden Jr., 26, of Clay Center, Kan.; and several other members of the crew were stationed.

A cockpit seat used by either Tennyson or McFadden had been located, according to the images from Project Recover and a sketch of the site drawn by DPAA forensic archaeologist Meghan Mumford.

The seat where radio operator Eugene J. Darrigan, 26, of Wappingers Falls, N.Y., sat was spotted earlier by Project Recover’s underwater cameras.

Darrigan had been a color mixer in a textile factory. His wife, Florence, 23, and 8-month-old son, Thomas, were back home in New York. He had seen Thomas once, when the baby was baptized.

The remains of navigator Donald W. Sheppick, 26, should “be found between the bombardier’s enclosure and the pilot/co-pilot’s seat,” Project Recover wrote in a 2018 report.

Sheppick was from Roscoe, Pa., a small town on the Monongahela River south of Pittsburgh. He had previously worked as a bank teller, according to Census records, and for Carnegie Illinois Steel, in nearby Homestead.

His wife, Mary, was pregnant with their son and living with Sheppick’s parents.

The nickname, Heaven Can Wait, probably came from a 1943 movie of the same name, starring the actor Don Ameche.

He had sponsored a different B-24, dubbed “Heaven Can Wait Don Ameche.” That plane was lost on May 4, 1944, elsewhere in the Pacific, according the Pacific Wrecks website.

Before any archaeology could start, the project had to make sure no bombs were with the wreckage. Last fall, divers went down to search.

Mumford, who was on the expedition, said the safety of the team is a priority. “As they’re excavating, there’s the possibility of unexploded ordnance being detonated,” she said.

No bombs were found, she said.

“I get goose bumps thinking about this,” said Jim Emmer, 75, of Victoria, Minn., a nephew of Army Staff Sgt. John W. Emmer Jr., who was a photographer and gunner on the plane.

John Emmer was 26 and had worked in the family lumber business in Minneapolis. Everyone called him “Johnny.” He had a girlfriend named Mary.

His mother worried about him being in the Army Air Corps. Three weeks before his death he wrote her, “God has looked out for me for two years now, and I guess he knows best.”

Jim Emmer said, “I just wish this was done when my father was alive. He was a very close brother to my uncle. So many people that have passed, this was a major event in their life growing up.”

He said John’s father was despondent after learning of his son’s death and was never the same.

“My grandfather just completely changed,” he said in a recent telephone interview. “He used to be a happy go-lucky, very personable man. He turned into pretty much a recluse.”

The United States entered World War II after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 7, 1941. By March 1944, the United States and its allies had begun to push back the Japanese advances in the Pacific.

The island of New Guinea, just north of Australia, was then part of the front lines, which sprawled thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean. Part of the island was in Japanese hands, and part was in allied hands.

On March 11, American B-24s based at Nadzab, in the southeastern section of the island, were sent to attack a big Japanese base at Boram, about 300 miles northwest.

On the return trip, Tennyson’s plane and two others flew to attack a secondary target – enemy antiaircraft guns at Awar Point on Hansa Bay, according to research by Scott Althaus and other members of the Kelly family.

As the planes approached Awar Point, Heaven Can Wait was hit.

“Flames started to pour from the front bomb bay,” eyewitness Staff Sgt. Arnold S. Smith, a waist gunner on a nearby B-24 reported. “In 2 or 3 seconds flames enveloped the plane from the first bomb bay to the tail.”

“Three men then jumped or fell out of the rear of the plane,” he reported. “The first man wore no chute and spread eagled straight down into the water… . I saw a white streamer as if from a chute coming from the second man but I did not see whether it opened.”

“The third man was wearing a chute but I did not see it open,” Smith recalled. “The tail assembly broke off and fell into the ocean. The plane banked left and drove in a slip into the water a quarter mile off the point.”

Other bombers circled near the crash site looking for survivors. “I could see no evidence that bodies remained at the surface,” Smith reported.

The 11 were classified as killed in action. After the war and an investigation by the American Graves Registration Service, their bodies were declared unrecoverable. Jean Tennyson got back her husband’s belongings and a government check for $84.19.

The modern quest for Heaven Can Wait began a decade ago when members of Kelly’s family, led by Althaus, a first cousin once removed and a professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, began digging into his story.

Over four years, Kelly’s relatives gathered a trove of data, and Althaus compiled a detailed report on the fate of the bomber and its crew. The family also located relatives of the other 10 men on board, said Sandy Althaus, 82, of Georgetown, Tex., Kelly’s cousin and Scott’s mother.

In 2016, the family reached out to Project Recover – formerly the BentProp Project – a partnership with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the University of Delaware.

Althaus sent the organization his report on July 31, 2017, and the following October, Project Recover found the plane.

Lt. Kelly was 21 when he was killed. He was from Livermore, Calif., about 40 miles southeast of San Francisco. He was gregarious and popular, and was known as “Toby.” He had a sister named Betty.

He was raised in a ranching family, had his own horse and wanted to be a cowboy when he grew up, Scott Althaus wrote in his report. In the service, he kept up a correspondence with 38 people back home.

The family still has dozens of his letters.

“I’ve heard the concept of generational grief,” said Kathy Borst, 69, one of Kelly’s nieces, who never knew him. “And I believe I experienced it. It was extremely powerful.”

“I can’t explain it,” she said. But if Kelly’s remains came home, the idea “that my grandmother, my grandfather, my mother and my uncle I never knew were in the same plot in Livermore has great meaning to me.”

She said in one of the last letters home, Kelly wrote: “I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I’m just telling you to appreciate what you have. Even if you don’t think it is much. It is so much. The men fighting here for everyone, they’re doing it for your freedom.”

She became emotional as she read the letter over the phone.

“Twenty-one years old,” she said.