In 2018, voters approved a $77 million library bond. The work touched every corner of Spokane

On a drizzly Friday afternoon, Amber Nilles sits back in her chair as her two small children, Paige and Clay, run and climb over a midsized play area.

Despite the gray clouds and wet ground, 1-year-old Clay’s clothes aren’t muddy and 3-year-old Paige’s glasses, tied to her head with a pink strap, aren’t fogging up. The play area that they’re exploring with a handful of similarly aged kids is inside the South Hill library, framed by floor-to-ceiling windows.

“I think it’s really cool, I like that there’s somewhere indoor to play that’s free,” Nilles said. “My kids are really little. Some places are too overstimulating or too big, and they could get hurt, and this place is pretty safe.”

It’s Nilles’ second time at the South Hill library, before or after the renovation paid for by a 2018 bond. She and her kids came for the first time a few weeks ago for the toddler story time hour, and the library had kept her kids interested with sensory toys and activities.

“I don’t think we would have started coming if we didn’t have somewhere for the kids to play,” Nilles said.

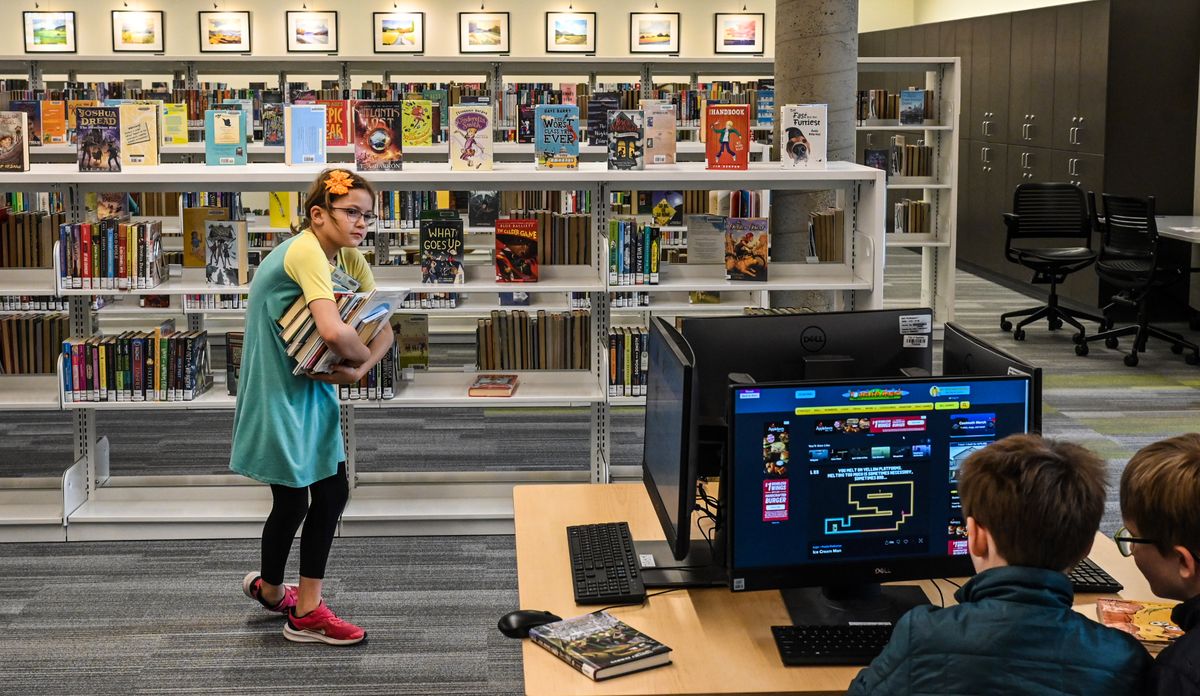

The children’s play areas, one of which is now located in each of Spokane’s libraries, clearly displays a change of strategy for the city’s library system as a result of the 2018 bond, when voters approved a $77 million property tax to build new libraries and renovate the rest.

“It can get noisy sometimes, but that’s what we planned for,” said Paul Chapin, operations manager for Spokane Public Libraries.

“The promise of what we were going to do, the two things, was meeting space and children’s and family areas.”

He gestured outside his office to the interior of the downtown Central Library, the largest and most expensive project that came out of the bond.

“We’ve gone from being a quiet, contemplative place to a real community center,” Chapin said.

That hasn’t meant that the libraries became useless to their traditional patrons. Librarians will occasionally ask kids to “walk with their quiet feet.”

Although an intermittent squeal or shout cuts through the quiet between the South Hill play space and the rest of the library, other patrons hardly seem to notice.

A medical student studying at the Washington State University Spokane campus plugs away for hours at a time in one of the study cubs: four miniature pods with tables, comfortable seating, a white board and a light with changeable colors.

Wandering the aisles nearby, Jane McLeish balances a stack of healthy cookbooks all by the same author, which she plans to peruse before deciding whether to buy any of them. At the sound of a quick joyous outburst from the play area, she looks up and lightly smiles.

“Libraries traditionally were quiet and you were told to hush, but I think any way you can get a child to a library is great,” she said.

Living within walking distance of the facility, McLeish had visited the South Hill library before its renovation a couple of times. But as she looks around at the wide aisles and comfortable seats and meeting spaces, she sees something transformational.

“It’s a gathering place now,” she said. “You can check out rooms and hold business meetings here, and there’s a lot more privacy areas.

“I think it appeals to a wider range of customer base, if you want to call them customers.”

Systemic transformation

The South Hill Library opened March 21 after nearly a year of renovations. Those cost around $5.5 million, using around 7% of the bond’s construction budget.

It was the last of the upgrades to the city’s libraries to be completed using funds from the 2018 bond, which was spurred by aging buildings and failing heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems.

The library system hadn’t undergone a major upgrade in nearly three decades.

“The city was asking us more and more to step up as a heat shelter and cooling center,” Chapin said. “The last year before we started construction, the hot weather snap really strained the system. Some cooling systems failed, especially in South Hill and Indian Trail.”

The Indian Trail Library, on the other side of town, opened just a few weeks earlier on March 7 after more than a year of renovations. That project cost a little over $4.8 million.

The Central Library downtown was by far the most expensive project in the system, running over $33.1 million, and opened in 2022.

“Before, Central had way too much space dedicated to staff and not enough to the public,” Chapin said. “It was kind of a vast warehouse of old documents and old books, but it was not public facing at all.”

When the Central Library reopened , it featured significantly more open spaces and tripled the number of meeting rooms, which had previously been overwhelmed by demand. It is now also open Sundays and later during the week.

Today, roughly 1,200 to 1,300 people visit the downtown location alone every day, Chapin said.

The Shadle Park and Liberty Park libraries both opened in 2021, costing over $14.6 million and $7.6 million, respectively.

The Liberty Park Library is a new facility, replacing the old library in the East Central Neighborhood that has since been converted into a police precinct.

It was also one of the first places where the design needed to be adjusted to make the space accessible to everyone, Chapin noted. When the Liberty Park library opened, the design relied heavily on natural light, which, while potentially lovely, was not always reliable.

“It’s a beautiful design, but not when you’re trying to find a book on the shelf and can’t see,” Chapin noted.

The Hive, also located in East Central, opened earlier in 2021. The new facility cost around $8.2 million to build, and is the only facility in the library system that doesn’t look at all like a library.

Instead, the space provides free meeting rooms that can hold dozens or upward of 100 people, with state-of-the-art technology to allow for hybrid meetings and presentation technology that can be easily used by anyone.

The space also holds four artist-in-residence studios, where artists can apply for one- to six-month residencies. If accepted – and it is highly competitive, with 73 applicants for the four spaces – artists can use the space continuously at no cost. In exchange, they provide free workshops to teach their craft or art to members of the public.

The space has hosted ceramicists, painters, a native canoe maker and many more. When weaver Judy Olsen applied for the program, she wasn’t certain if she could be considered an artist, despite her 30 years with the Spokane Handweavers’ Guild. She’s a craftswoman, an engineer who rebuilds old looms, but asking to be recognized as an artist was intimidating.

Still, despite the competition for the space, Olsen was accepted. She retired from her part-time job at Fred Meyer so she could meet the residency’s 20-hour-a-week requirements and got to work, filling the space with hand-restored looms and thread hand-dyed with iron, hibiscus and alkali.

Now, with less than a month left to her residency, sitting next to a vintage great spinning wheel she believes can be traced to Shakers from Maine, she contemplates what the space has meant to her. She wondered at first whether she would be sick of weaving by the end of the residency, but the passion hasn’t waned.

Although she’s ready to spend some time planting in her garden as spring gets underway, she’s particularly grateful to have introduced others to her craft.

“The magic is in their hands,” she said. “And for me to be able to sit here and watch. I mean, I’m getting goosebumps just talking about it.”

A few feet down the hallway, Mallory Battista is hard at work finishing a massive plaster and glass mosaic sculpture she has been building for months with Lisa Soranaka. It will soon greet visitors to the Emerson-Garfield Neighborhood.

Over 250 of the pieces Battista is methodically adhering to the sculpture were crafted by community members who attended one of their workshops, ensuring that there will be a cadre of residents with a personal stake in the piece of public art.

Battista and Soranaka had wanted to get their start in public sculpture . They found it difficult to not only find that first job, but also a space large enough for them to work.

“We wouldn’t have been able to do this without (The Hive),” Battista said. “Even with the community support we’ve gotten, and our motivation to get it done, this space was really the thing that made it all possible.”

The Hillyard Library was the first to be completed. Despite being a new facility, it was also the cheapest to the library system due to a partnership with Spokane Public Schools. The Hillyard Library, which cost the library system less than $500,000, is actually built into Shaw Middle School.

Though $77 million is a large price tag, Chapin noted just one of the city’s new middle schools could run upward of $70 million.

“We did seven buildings, and we thought we did it pretty well, to be stewards of the public investment,” Chapin said.