State biologists confirm wolf pack on Mount Spokane during annual wolf survey

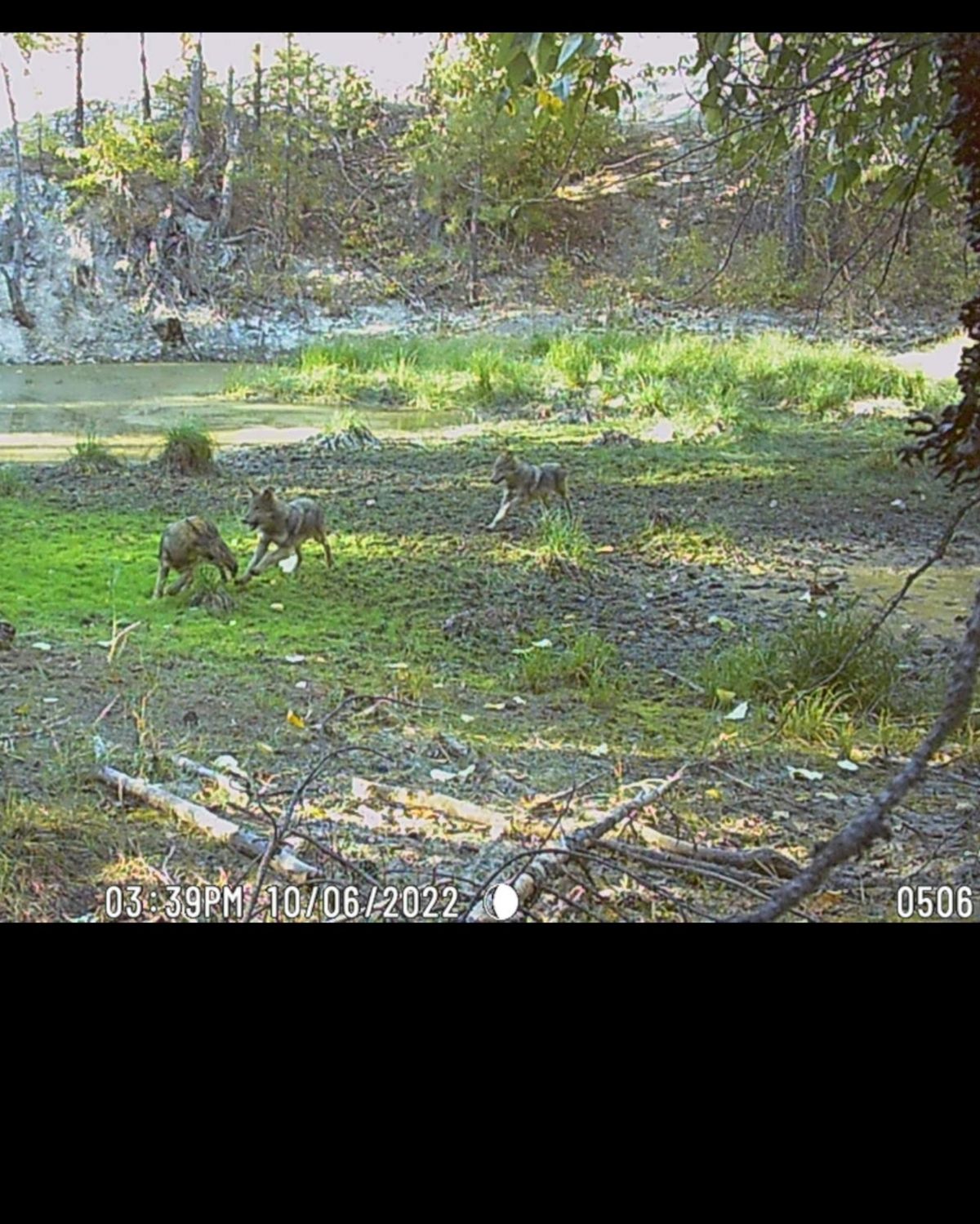

Washington biologists confirmed the existence of a wolf pack on the western flank of Mount Spokane on Friday. Here is a trail camera photo from Arthur Cooke of the pack. These photos were taken in the fall and shared with Washington biologists who later confirmed the existence of the wolves there. (Arthur Cooke/Courtesy)

Washington biologists on Friday confirmed the existence of a wolf pack on the western flank of Mount Spokane.

The pack, dubbed the Mt. Spokane pack, was first spotted by hunter Arthur Cooke and has a minimum of four members. Cooke set a trail camera out on Inland Empire Paper land in preparation for hunting season last fall.

“I thought it was just a bunch of turkeys,” Cooke said. “But it turned out it was a bunch of wolves.”

Cooke sent those photos to Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists and in January and February biologists confirmed the existence of that pack by finding tracks in the snow, including the tracks of wolf pups.

“It’s neat to see. But they are starting to get close to town,” Cooke said. “There are a lot of people who live out in that area.”

That closeness doesn’t surprise Trent Roussin, a Department of Fish and Wildlife wolf biologist.

“Wolves will live wherever humans tolerate it,” he said. “And there are plenty of ungulates in that area.”

However, the fact that there are a number of smaller landowners on Mount Spokane means avoiding conflict will take more work.

“It’s just a lot more work from a conflict prevention standpoint,” he said.

Biologists also confirmed a pack in the Southern Cascades and the Northwest Coast recovery region; an important step toward full statewide recovery per the state’s wolf plan.

“That expansion into the South Cascades is a pretty big deal,” Roussin said. “Our recovery objectives require that we have four breeding pairs down there and until this year we haven’t even had a pack there.”

Statewide Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and tribal biologists counted a minimum of 216 wolves in 37 packs as of Dec. 31; 26 of those packs were considered successful breeding pairs. In the previous survey biologists counted 206 wolves in 33 packs. This is the 14th straight year Washington’s wolf population has grown, according to the state.

As in years past, most of those wolves live in the eastern third of the state. Per the state’s recovery plan, wolves can only be delisted after 15 successful breeding pairs are documented for three consecutive years, or after officials document 18 breeding pairs in one year.

Under either scenario, the pairs have to be distributed evenly throughout the state’s three wolf management areas. The agency once predicted wolves would disperse throughout all three recovery zones by 2021.

While some are anxious for dispersal to happen faster, Julia Smith, the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s wolf policy lead, pointed to the larger context.

“A lot of folks seem to think 14 years is a long time and it’s not,” she said. “It’s not an overnight process. And the fact that we see it unfolding as fast as it is is incredible to me.”

The Fish and Wildlife department spent more than $1.6 million on wolf management in 2022. That included nearly $57,000 in reimbursement to 26 livestock producers nonlethal conflict prevention expenses, including range riding, specialized lighting, fencing and more; about $230,000 for 16 contracted range riders; $8,000 for direct claims for livestock losses caused by wolves in 2021 but paid in 2022; $6,000 for indirect claims for livestock loses in 2021 but paid in 2022; $120,000 for lethal removal operations in response to depredations on livestock; and $1.2 million for wolf management and research activities.

During 2022, wolves killed 15 cattle and two sheep, according to confirmed state investigations; meanwhile nine cattle were confirmed as injured and two were probably injured by wolves in 2022.

Overall, seven packs were involved in a livestock attack of some sort. Only three packs were involved in two or more depredations. In 2021, wolves killed five cattle and inured eight, according to the state. In response, the Fish and Wildlife Department killed two wolves.

Smith said this year’s number of livestock depredations are “pretty much baseline normal, just what you’d expect.”

In 2022, 37 wolves died. That included six killed by the state following livestock attacks, three that were caught in the act of attacking livestock and six poisoned illegally in northeast Washington. That investigation is still underway, according to the state Fish and Wildlife report. Three others were illegally killed in separate incidents.

Meanwhile, seven more died of natural causes, including two killed by cougars, one killed by a moose, one killed by other wolves, two of old age, and one pup that died from malnutrition, one unknown death and 11 wolves that were legally killed by tribal hunters, according to the state report.

Biologists gather information about wolves during the winter and early spring using a variety of methods, including tracking, camera traps, radio-collared information and citizen reports.

Wolves are federally protected in the western two-thirds of the state and on the state endangered species list in the eastern third of the state. For 13 months in 2021 and 2022, wolves were removed from the federal endangered species list. A U.S. District judge in California, however, ordered the wild canines back onto the list in 2022.

Wolves were eradicated from Washington and most of the western U.S. by the 1930s following a concentrated hunting, trapping and poisoning campaign.

Following reintroductions in Idaho and Montana, gray wolves naturally returned to Washington, with the first pack documented in 2008.