‘He kept reporting’: Bill Morlin, Spokane journalist revered for dogged coverage of extremism, honored with posthumous WSU award

The late Bill Morlin’s impact as an investigative reporter covering extremism, corruption and crime for The Spokane Daily Chronicle and The Spokesman-Review still reverberates throughout the region.

“He is the journalist of the journalists in the Pacific Northwest, a guy who dedicated his entire life to covering his hometown with thoughtfulness, integrity and ethics,” said Ben Shors, Department Chair of Journalism and Media Production at Washington State University’s Edward R. Murrow College of Communication.

Morlin, who died in 2021 of complications of an intestinal infection, spent decades covering extremism in the Inland Northwest. In his nearly half-century career at Spokane newspapers, his award-winning coverage of the Aryan Nations compound in North Idaho and domestic terrorist groups led Morlin to be considered the pre-eminent reporter on extremism.

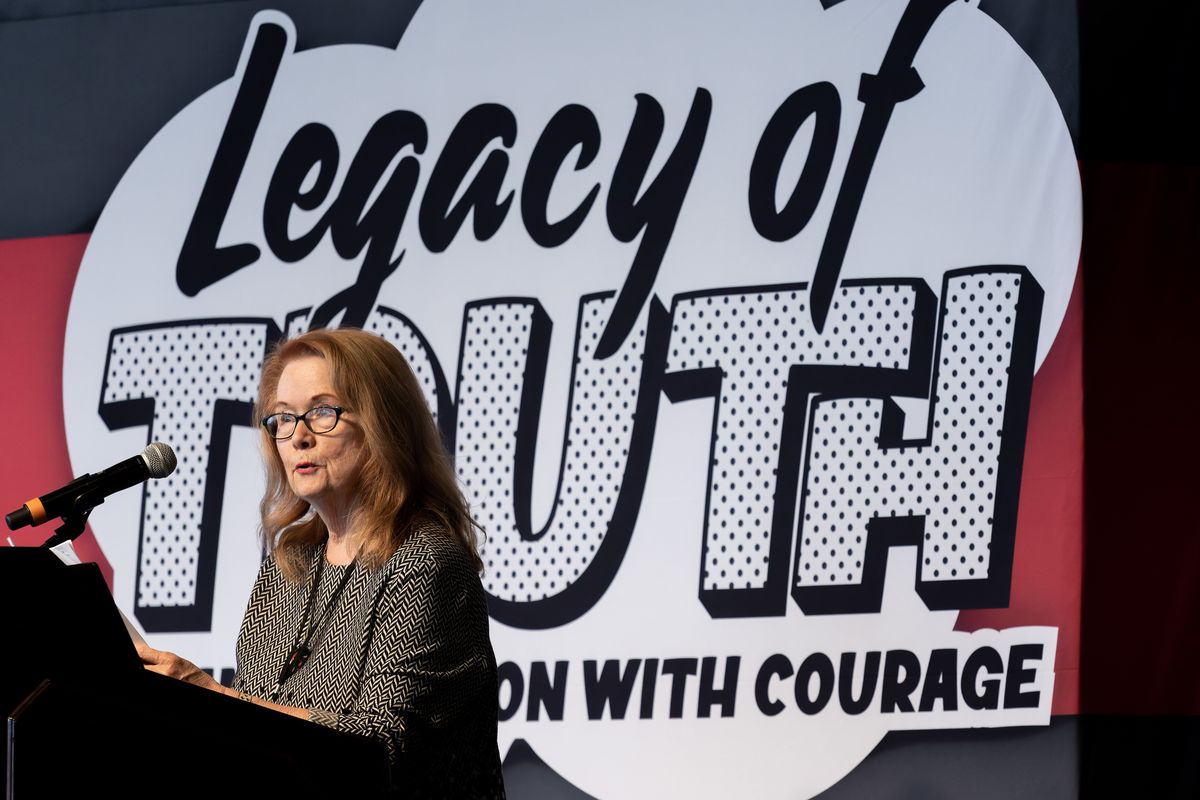

In a crowded ballroom at WSU’s Compton Union Building Wednesday afternoon, the Murrow College recognized Morlin for his decades of hard-hitting coverage during the 47th annual Murrow Symposium. His wife, Connie Morlin, accepted the honor on his behalf after former collaborator Karen Dorn Steele gave a heartfelt account of Morlin’s career.

Morlin’s recognition by the Murrow College was spurred by Shors, another former colleague of Morlin. Shors spent seven years at The Spokesman-Review investigating social and environmental issues in the early 2000s.

“Bill was a tireless investigative reporter who never cowered in the face of terror,” Shors said. “When a neo-Nazi pulled a gun on Bill Morlin, he kept reporting. When the Aryan Nations put him on his hit list, he kept reporting. When an extremist group bombed The Spokesman-Review, he kept reporting.”

Dorn Steele, a 1995 Washington state Hall of Journalistic Achievement inductee, worked closely with Morlin during her decades at Spokane newspapers. Dorn Steele is known for her investigative reporting on public health issues stemming from nuclear testing at the Hanford Nuclear Site, the involvement of Spokane-based psychologists in the CIA’s “rendition” torture programs following 9/11 and Spokane Mayor Jim West’s use of city computers to search dating sites – an investigation headed by Dorn Steele and Morlin.

“When I joined the Chronicle staff in 1983, after an early career in public television, I already knew that Bill was special,” Dorn Steele said.

A third-generation Spokanite, Morlin’s reporting strengths were his steadfast commitment to his community and a seemingly endless network of sources, she said.

Dorn Steele shared recollections from former reporter and longtime Spokesman-Review contributor Jess Walter, now a bestselling author. Morlin provided research and reporting for Walter’s first book, “Every Knee Shall Bow,” which delves into the fatal federal standoff in North Idaho known as Ruby Ridge – named for a geographic marker Morlin identified covering the incident.

Dorn Steele recalled how Morlin was fearless while covering the extremist fringes of society in the Inland Northwest. She shared a quote from a conversation she had with Walter while preparing for her speech that highlighted Morlin’s candid nature when covering extremist hate groups like the Aryan Nations.

“Bill would get in their faces and ask just a barrage of questions,” Walter told Dorn Steele. “My tendency as a reporter was to sneak around, get some information and then approach them with some trepidation. Bill told me to just go up and ask them. He greeted them by name.”

Morlin’s impact stretched far beyond the stories he covered , Dorn Steele said. He frequently was consulted on national stories that involved extremism and domestic terrorism, and he was a staunch supporter of young reporters following in his footsteps.

Freelance extremist reporter and author Leah Sottile was one of many young journalists Morlin mentored . In an email, she echoed Dorn Steele’s remarks about his dogged nature and commitment to exposing hatred, corruption and extremist movements.

“My relationship with Bill was by and large over the phone,” Sottile said. “I’m a freelancer with no colleagues and no newsroom, and Bill was willing to be my colleague. I always found that to be so kind: that he was willing to spare time from his retirement to talk about extremism with me.

“But I think extremism is one of those beats that once you do it, you find a need for kinship with other people who are willing to take on this crazy work.”

In the decades since Morlin started reporting on extremism, other outlets and reporters have started taking fringe movements more seriously, Sottile said. Sottile and Dorn Steele acknowledged the criticisms often levied at Morlin’s reporting: Those groups should not be given attention.

“But he remained steadfast that turning a blind eye to hate movements would not make them go away,” Sottile said. “During my conversations with Bill, he was clear that the things that he used to hear from the pulpit at the Aryan Nations were being expressed by the president of the United States, Donald Trump.”

Shors echoed Sottile’s comments, emphasizing that in the ’80s and ’90s, extremist movements flew under the radar.

“I think he would welcome more people focusing on this; the fight goes on,” Shors said. “It didn’t end in 1995, it didn’t end when he retired, it goes on and it will go on for generations.”

Sottile said it is important for younger journalists to understand the work of those who came before them, like Morlin.

“Bill is an example of someone who believed in his reporting and fought hard for it,” Sottile said. “And because of that willingness to fight for his work, the world is better for it.”

Bill Morlin died of sepsis in the same Spokane-area hospital where he was born.

Connie Morlin said her husband was mentoring and reporting from his hospital bed, providing Sottile notes on an advanced copy of her book on extremism, “When the Moon Turns to Blood: Lori Vallow, Chad Daybell, and a Story of Murder, Wild Faith, and End Times,” which she dedicated to him.

Connie Morlin said he told her to make sure to “tell Leah I’m still working on it.”

In the days preceding his death, Connie Morlin said two things put a smile on his face. The first was hearing a handwritten letter he received from Dorn Steele that recounted how much he had meant to her.

The second was a call from Shors in which he told him he would honor his legacy .

“My husband had these piercing blue eyes,” Connie Morlin said. “His blue eyes were twinkling; he was just so pleased and just so grateful.”