Day by day, an artist chronicled two years of covid in America

Chronicling the pandemic through art was “a day-to-day reaction,” said Steve Brodner, pictured in his New York studio. Nearly two years of illustrations are collected in his new book, “Living & Dying in America.” (Leo Sorel)

Steve Brodner sat in his Upper West Side art studio in the spring of 2020, absorbing the obituaries as the whir and cry of dead-of-night ambulances broke the city’s disquieting silence. It was all moving too fast.

Day after day, name after name, he couldn’t shake the sense that COVID-19 victims were dying in waves too great for them to be properly appreciated. As the lockdown lasted, he thought: “We’re losing these people and they’re really important, even though we’ve never heard of most of them.”

So Brodner, an illustrator and political caricaturist, carried out one personal act each day. He would pick up his pen and brush to spotlight a prominent aspect of the coronavirus pandemic from the current news cycle – one face or event at a time.

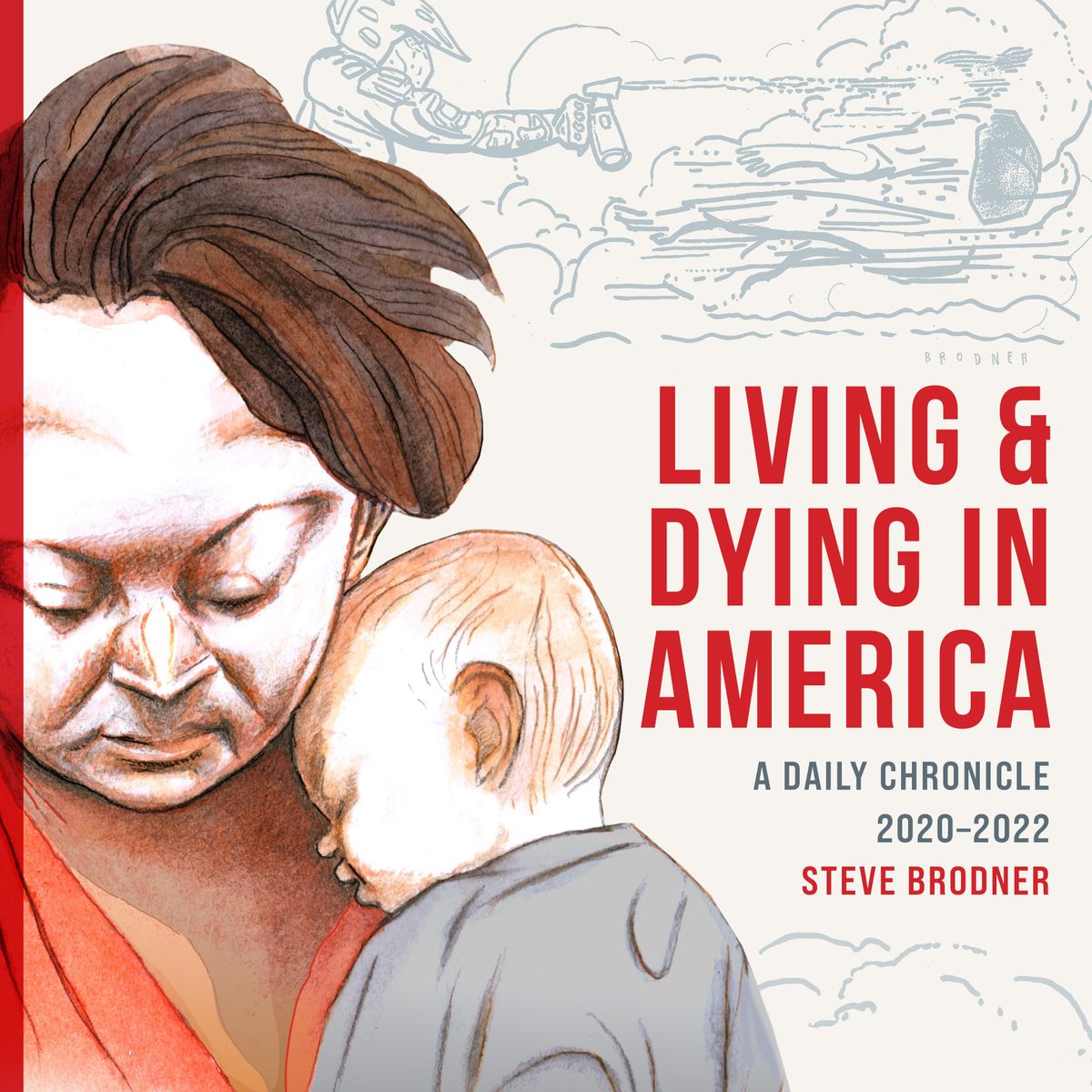

Now, his heartfelt portfolio of ink and paint snapshots is collected in the new book “Living & Dying in America: A Daily Chronicle 2020-2022” – a real-time remembrance of how the pandemic brought out the best and worst of us during its first 22 months.

The book illuminates sacrifice and support, disregard and denial. And it gathers a cumulative force as its human mosaic grows more intricate. On one page is a medical worker making do with too little equipment; on another is a politician seemingly making up information that has too little basis in fact.

The spirit of the project, though, was sparked by Kious Kelly.

Kelly, 48, was a nurse at Manhattan’s Mount Sinai West hospital who contracted the virus in March 2020. He is believed to be the first New York health care worker to die of COVID-19.

Once the artist read about Kelly, he was moved to create a tribute image.

“This young man essentially gave his life to save his patients,” Brodner said. “According to his family, he just felt it was really necessary to keep going to work – to be there for these sick people.”

Brodner began to draw from a photo of Kelly. He then posted the artwork on his social media accounts.

“I looked at it and thought: Yeah, let’s do more.”

This exercise in daily documentation was a way for him to cope with the speed of the virus’ toll.

“I felt when I started to do them that I was stopping time just a little tiny bit,” the author says by phone from Manhattan. “I want to look at their faces. I want to hear their stories. I want to hear their voices, if possible.” (Disclosure: Brodner has contributed art to The Washington Post.)

The scope of the project grew considerably, but early on, Brodner gained steady momentum by keeping it simple. A few lines of ink. A few lines of prose.

The artist wanted each portrait he shared on social media to stand as a marker – as “a symbol for that life,” he said. “Like a kind of a gravestone, or a little memorial card that you would slip into a wall or display.” Some loved ones of the victims sent notes of appreciation to him.

Yet Brodner, 67, said much of his half-century-long career has involved imbuing his art with his pointed outlook. So, increasingly, he drew other voices and news stories that also reflected the pandemic era, particularly as he realized that the U.S. COVID response exposed ways in which “we are not all in this together.”

In one Brodner portrait, a Houston medical worker describes how he has to tell some COVID patients: “I don’t have enough beds for you.” In another illustration, a woman at a Houston rodeo says of masking: “It’s against our constitutional rights. They shouldn’t be able to dictate what I wear.”

“Living & Dying” grows particularly critical of leaders who minimized the perils of the pandemic or who opposed lockdowns. “There are people who should not be let off the hook,” the artist said of such political responses to the virus, which has killed more than 1 million Americans.

Brodner sought to hew to physical and emotional truths. He has an initialism he uses when teaching his art students at New York’s School of Visual Arts: “D.M.I.U.”

“Don’t Make It Up – I write that on their papers,” said Brodner, underscoring that “when you’re drawing a face, you have to really look at the face.” He added: “You’re consciously or unconsciously entering into that person’s world.”

That approach heightens his sense of artistic sympathy. In his studio or at his dining room table late at night, he would become overwhelmed with sadness: “I would sit and feel the loss.” He didn’t know any of the victims he rendered, yet he felt such a strong emotional bond that he would weep. (Brodner, who is vaccinated and boosted, notes that neither he nor his acupuncturist wife has contracted COVID.)

As Brodner chose whom to spotlight, he was particularly affected by the loss of a nurse, a cancer-surviving boxing coach, musicians and Nick Cordero, the Broadway actor who died in the summer of 2020, at age 41.

He created these portraits to connect and to cope.

“That was the only reason to do this,” he noted, “because I felt it.”

He paused a moment and said: “I think that’s why we make art.”