Fiona strengthens to a hurricane as it reaches Puerto Rico on Sunday

Tropical Storm Fiona strengthened Sunday to a hurricane as it reached Puerto Rico, and forecasters warned it could bring as much as 25 inches of rain to some places and cause life-threatening floods and landslides.

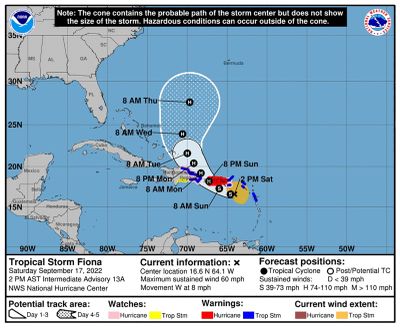

Maximum sustained winds had increased to nearly 80 mph, the National Hurricane Center said Sunday morning. Hurricane warnings were posted for Puerto Rico and the coast of the Dominican Republic from Cabo Caucedo to Cabo Frances Viejo, the center said.

In Puerto Rico, rainfall totals could reach 12 to 16 inches, with local maximum totals of 25 inches, particularly across eastern and southern Puerto Rico, forecasters said.

“These rainfall amounts will produce life-threatening flash floods and urban flooding across Puerto Rico and portions of the eastern Dominican Republic, along with mudslides and landslides in areas of higher terrain,” the Hurricane Center said.

The National Weather Service office in San Juan on Sunday said the streamflow of the Rio Blanco had increased and warned that residents along that river and other flood-prone areas should consider moving to higher ground.

The memories of Hurricane Maria, which slammed the island in September 2017 as a Category 4 storm, are still fresh on the minds of Puerto Ricans. An estimated 2,975 people died in the storm, and the response to the disaster sparked political unrest.

As of Sunday morning, more than 257,000 customers were without power in Puerto Rico, according to poweroutage.us, which tracks power interruptions.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency said it had been in touch with Puerto Rican authorities and that the agency had nearly 80 people on the ground to provide federal support and coordinate an emergency response. President Joe Biden on Sunday approved an emergency declaration for Puerto Rico, which authorizes federal agencies to coordinate disaster relief efforts.

As of 8 a.m. Sunday, the tropical storm was about 65 miles south-southeast of Ponce, Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico’s governor, Pedro R. Pierluisi, declared a state of emergency at a news conference Saturday morning.

The power went out for a few seconds during the news conference, a reminder that unreliable electricity remains a common problem on the island, five years after its outdated infrastructure was severely damaged by Hurricane Maria.

In Puerto Rico, the storm surge and tide could flood normally dry areas along the coast, and forecasters warned that the water could reach 1 to 3 feet on the southern coast if the peak surge occurred at high tide.

The storm could bring 4 to 6 inches of rain to the British and U.S. Virgin Islands and up to 10 inches on St. Croix, forecaster said.

A hurricane watch was in effect for the U.S. Virgin Islands and the north coast of the Dominican Republic from Cabo Frances Viejo westward to Puerto Plata.

The storm is expected to strengthen Monday and Tuesday as it moves near the Dominican Republic and over the southwestern Atlantic, the Hurricane Center said.

The Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June through November, had a relatively quiet start, with only three named storms before September. There were no named storms in the Atlantic during August, the first time that happened since 1997. But storm activity picked up in early September, with Danielle and Earl, which both eventually became hurricanes, forming within a day of each other.

In early August, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued an updated forecast for the rest of the season, which still called for an above-normal level of activity.

In it, they predicted the season could include 14 to 20 named storms, with six to 10 turning into hurricanes that could sustain winds of at least 74 mph. Three to five of those could strengthen into what the agency calls major hurricanes — Category 3 or stronger — with winds of at least 111 mph.

Last year, there were 21 named storms, after a record-breaking 30 in 2020. For the past two years, meteorologists have exhausted the list of names used to identify storms during the Atlantic hurricane season, an occurrence that has happened only one other time, in 2005.

The links between hurricanes and climate change have become clearer with each passing year. Data show that hurricanes have become stronger worldwide during the past four decades. A warming planet can expect stronger hurricanes over time and a higher incidence of the most powerful storms — though the overall number of storms could drop, because factors like stronger wind shear could keep weaker storms from forming.

Hurricanes are also becoming wetter because of more water vapor in the warmer atmosphere; storms like Hurricane Harvey in 2017 produced far more rain than they would have without the human effects on climate, scientists have suggested. Also, rising sea levels are contributing to higher storm surge — the most destructive element of tropical cyclones.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.