Remote work allowed more people to move into rural areas like the Methow Valley, but locals now worry about housing, staffing

Beverly Nieves, who until recently had never used a laundromat, pauses while doing her laundry at 1 a.m. Friday at Pine Near RV Park in Winthrop, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

WINTHROP, Wash. – What Beverly Nieves misses the most about owning a home is having a kitchen.

Nieves, 75, used to cook for herself all the time – mostly healthy, balanced meals, and lots of seafood. Now, she lives in a shared apartment owned by her employer, whom she relies on for two meals a day.

It’s a two-room apartment with only a fridge and a microwave. Not even a kitchen sink. She shares a bathroom with other employees and, for the first time in her life, she goes to a laundromat.

“These are things I’ve never dealt with in my life,” Nieves said. “It’s such an adjustment for me.”

Nieves had owned a home since she was 23. Originally from Nova Scotia, Canada, she lived in the Methow Valley for almost 20 years, working as a massage therapist at the Valley’s large ski resort. She moved away in 2015, only to realize she wanted to move back three years later.

When she did, she found the housing market had completely changed. She could no longer afford to buy a house.

She moved between five temporary housing situations, from room rentals to a motel to a “fabulous” guesthouse that she knew was only short term.

Now, she lives in a two-room apartment renovated by her boss.

It’s a common occurrence in the Methow Valley, which has seen a sharp increase in people moving into the area who often earn much more than locals.

Locals say a growing wealth gap has caused a sharp spike in housing costs, and many longtime residents – especially service workers – have struggled to stay in rentals or buy homes. Employers have started housing their workers. Some people sleep in their cars in the summer and on friends’ couches in the winter.

In town, the amount of additional people in recent years does not go unnoticed. Roads are busier than they were five years ago, auto work is hard to come by, doctors appointments could take months and tradespeople, like plumbers, are few and far between.

A man crosses a street on Friday morning in Winthrop, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Growth from remote workers, people with second homes

The Methow Valley sits on the eastern edge of the North Cascades, encompassing the towns of Mazama, Winthrop, Twisp and down to Pateros, Carlton and Methow.

It’s known for its access to outdoor recreation, its arts scene and its Wild West-style towns. With some of the most cross country ski trails in North America, it attracts loads of tourists in the summer and winter.

The Valley has a small-town feel and a tight-knit community where everyone seems to know everyone.

But the COVID-19 pandemic hit brought a “Zoom boom:” People from Seattle and other parts of the West Side could work remotely and looked for a place to go to escape the city. Some already had second homes in the Methow Valley hills. Others were discovering it for the first time.

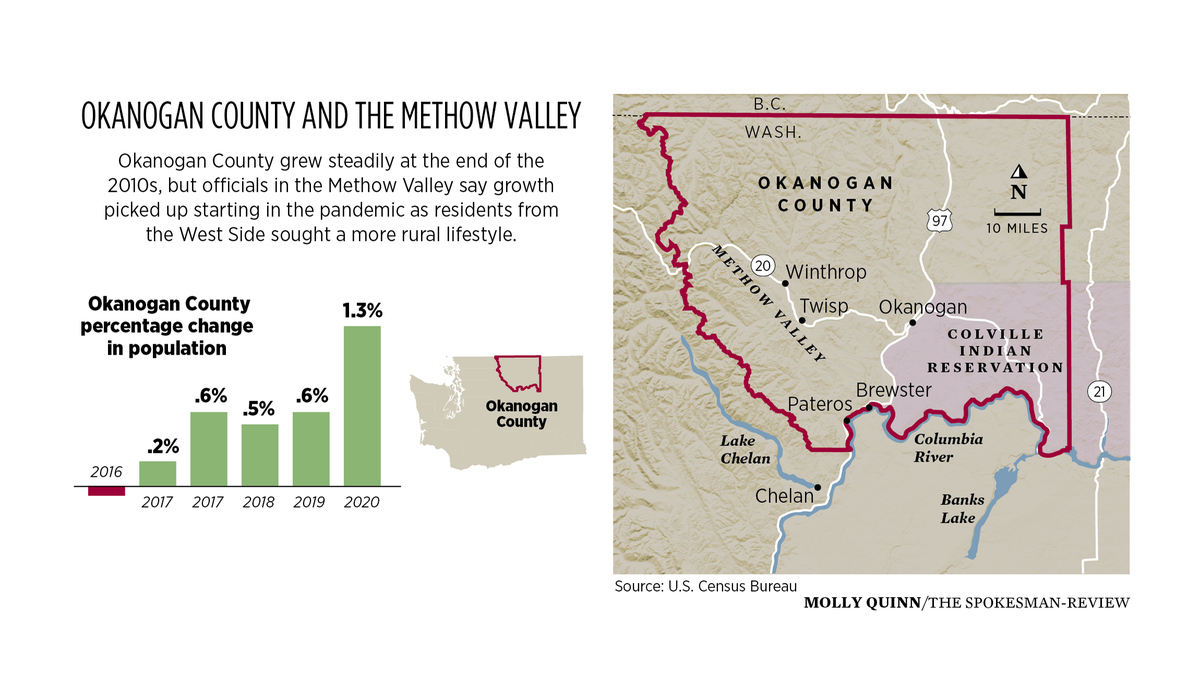

Data from the 2020 U.S. Census for Okanogan County does not necessarily reflect the recent growth of the area, as much of it happened in the past few years since data was collected. Between 2010 and 2020, the county grew by about 2.4%, according to the U.S. Census.

Data from the American Community Survey shows Okanogan county grew by about 1.3% between April 2020 and July 2021 alone. The American Community Survey collects data every year to deliver population estimates between census counts every 10 years.

According to the same data, Spokane County grew by about 1.2% while King County decreased population by about 0.8% between April 2020 and July 2021.

According to a comprehensive economic study done in 2020 and 2021 by local nonprofit TwispWorks, more than 1,000 homes were built in the Methow watershed between 2005 and 2020. There are 6,400 full-time residents and 4,380 part-time residents in the area, fueled primarily by amenity migration during the COVID-19 pandemic. More than 30% of the population gets at least part of its income from outside the Valley.

Remote workers make significantly more than those who live and work in the Methow. The median household income for families who live and work in the Methow Valley is $57,779, while nearly 60% of working families make less than $55,000 a year, according to the TwispWorks economic study. About 30% of jobs in the Methow are in retail or recreation services.

Remote workers have a median wage of $202,000.

Housing prices have increased rapidly, up by 14.7% from 2020, according to the economic study. Between 2018 and 2020, the average price increased by $105,000, up to $499,000 today.

Rental options are slim. The few that exist are expensive or short term.

It’s a situation that many in the community worry will cause the area to follow in the footsteps of Vail and Aspen, Colorado, Jackson Hole, Wyoming or other mountain towns where service workers live hours out of town and bus in for work every day.

But many community members want to try everything to avoid that.

Businesses struggle to keep staff

When Jacob Young, an owner of the Old Schoolhouse Brewery, heard one of his brewers had to leave town because she couldn’t find housing, he took action.

He and his wife already were planning to renovate a mother-in-law unit on their property. He decided to finish it and allow his employee to move in.

“I couldn’t risk losing her as an employee,” he said.

But then he found she wasn’t the only employee who needed help with housing. Young bought a double-wide trailer with three bedrooms that he rents out to employees who need a place to stay.

“Of all the things I thought I would spend money on when owning a business, this was not on the list,” Young said.

The Old Schoolhouse Brewery has three locations across the Methow: one in Twisp, one in Winthrop and one new location in Mazama. Young works the line most days at the new Mazama location because there’s not enough staff to keep it running, he said.

Three Fingered Jack’s Saloon in Winthrop often has a long wait for a table because there isn’t enough staff to serve everyone, owners Patti Lukas and Seth Miles said.

There’s a “high cost of living with the low cost of wage” in the Valley, making it hard for service workers to live there, Miles said.

While they’d love to offer higher wages, they also have to sustain themselves, said Miles, who also sits on the Winthrop Town Council.

“We’re not making millions of dollars,” he said.

When it comes to housing, community leaders say there are three areas that need to be addressed. Those are homeownership, long-term rentals and seasonal or transitional rentals, said Simon Windell, chief operating officer at the Methow Housing Trust.

In the first five months of the year, the nonprofit Room One, which provides social services to residents, has had 49 individuals or families come in to discuss a housing issue, Executive Director Kat Goering said. Those could be people needing help with something like applications or a landlord concern.

Thirty additional people came to Room One to discuss issues surrounding homelessness and needing help with services or housing, she said.

There is no emergency shelter in the Valley, so when someone is homeless, they often have to stay in a motel or on a friend’s couch until they can find another place to live.

“Almost any conversation in this area will circle back to housing,” Young said.

But the community has other needs, such as support for an aging population and more child care services.

Nearly 40% of the population is over 60 years old, according to the TwispWorks study.

Most older people in the Valley need help, longtime resident Karen West said.

“A lot of people age out of the Valley because of their health,” she said.

On the other end of the spectrum is a growing need for child care, as the Valley only has one licensed child care provider with two locations.

Because many staff can’t afford to live in the area, it’s hard for a child care provider to expand, said Sierra Golden, associate director at TwispWorks.

Community comes together to find solutions

The Methow Valley has dozens of nonprofit organizations, and most of them are working together to find solutions to the housing crisis.

People in the Methow understand how other mountain communities, like Vail or Aspen, transformed quickly have changed quickly and want to get ahead of the rapid growth, said Sarah Brooks, associate director at the Methow Conservancy.

“It has been changing rapidly here too, but because we’ve had this steady stream of conversation, we’re able to try to respond quickly,” she said.

People in the Methow know how to identify a problem and think of a solution, fourth-generation resident Kit Cramer said.

In the TwispWorks study, suggestions for addressing affordable housing include reallocating lodging and hotel taxes to pay for affordable housing, imposing deed restrictions on home sales for local and working residents, and construction of affordable housing units and multiple dwelling homes.

One idea that came out of a number of devastating wildfires in the area was the Methow Housing Trust, which formed in 2017.

The program uses a community land trust model where it builds houses on land owned by the trust. It then sells the homes to members of the community at an affordable price, which is either 60% to 100% of the average median income or up to 150% of the average median income.

The trust still owns the land that the house is built on, but Executive Director Danica Ready said it doesn’t feel any different than them owning a home.

“Our goal is to create permanent affordability in a home,” she said. “That’s the business we’re in.”

The trust has built and sold 26 homes with a plan to finish 74 total in the next five years. There are 57 families that are eligible and on the wait list, Ready said. She said they will continue to find land to fit the needs.

“Is it enough? We’re still learning,” she said.

A number of other developments are in the works to increase affordable housing, according to reporting from the Methow Valley News.

A 17-acre development on the “schoolhouse hill” in Twisp would allow for 53 homes with lots ranging from 3,700 square feet to 10,500 square feet, though the application also requests there be homes as small as 700 square feet.

The town is also considering requests from Hank and Judy Konrad, who own Hank’s Harvest Foods, to annex two properties into the town’s limits to develop affordable housing. It would allow for about 10 acres that could be developed.

The planning commission has given preliminary approval to a 10-unit townhouse in Twisp, but it still is awaiting final approval.

Despite the housing crisis, residents also acknowledge there are some benefits that come with more people.

One example: more kids in the school system, meaning more parents who want to be involved in the system. Levies pass consistently, said Sarah Brown, executive director at TwispWorks.

“When you’re supporting a school district with a broad spectrum of economic diversity, that means that kids are getting supported,” Brown said. “And that is something that leads to a stronger community.”

There are also more people who are involved in the community and want to help be a part of the solution, Brooks said.

Brooks said the Methow Valley is not an easy place to live with difficult winters and summers. It’s also not easy to travel to or to make a living, so the people who do move there want to be involved in the community, she said.

“People who come here choose to be here,” Brooks said. “And that means you want to be a part of whatever that is that drew you here.”

Housing search continues for many

Like Nieves, Trent Peterson moved out of the Methow Valley for years only to come back in May to a completely different housing market.

Peterson, 38, and his girlfriend live in an apartment in town with what he calls “decent rent.” But he knows he only found it because he already knew people in town who could help him.

They’re trying to find a place to buy or a better spot to rent.

Ideally, it would be anything that’s not an apartment. There would be land for their horses to live and at least two bedrooms for them and their 13-year-old son.

Peterson, who works for the U.S. Forest Service, said their budget is tight.

“We just can’t seem to make that happen,” he said.

He doesn’t fault people for wanting to move into the area, but he said it’s frustrating when landlords use that opportunity to maximize their rental income.

Most people who want to buy in the area find themselves on the list for the Methow Housing Trust.

Becky Jones, 69, was on the list for a home with the Methow Housing Trust for almost four years. Her wait was slightly longer than normal because she wanted one of the new homes in Winthrop as opposed to Twisp.

Jones, who owns the Winthrop Beauty and Styling Parlor, said she did not feel secure in renting because she saw so many rentals being sold as more people moved in to the area.

She ended up with a one-bedroom house that she said is “very, very nice and spacious,” has a yard and is close to her job.

“They’re not just little cheap houses,” she said. “They are beautiful and well-made.”

Nieves said she’s been on the housing trust waiting list since fall 2019. Her ideal home would be a two-bedroom with her own appliances, a bathtub and, of course, a kitchen.

Nieves is confident she’ll have a home again, but knows it may not be for at least another year when she’s able to get off the list.

Until then, she’s happy being where she wants to be: back in the Methow Valley.

She moved back to the Methow Valley because she missed the quality of life. The community becomes an extended family, she said, and the natural beauty, outdoor recreation and performing arts are all pluses.

“Those are the things that saved me,” she said.